Abstract

There are hundreds of alphabetic texts in Zapotec languages dating back to the

16th century. Today, however, Zapotec speakers are generally unable to read

these texts, due to lack of access to the texts and an unfamiliarity with the

orthographic practices. Moreover, significant changes have taken place in the

grammar in the intervening centuries. This results in a situation where Zapotec

people may not have access to history in their own language. Ticha is an online

digital text explorer that provides access to images, transcriptions, analysis,

and translations of the Colonial Zapotec texts. The Ticha project includes

in-person workshops with Zapotec community members as part of an iterative

development process. Feedback from these interactions inform design decisions

for the project. Here we reflect on transnational collaboration with

stakeholders in building a digital scholarship project that seeks to use the

power of digital humanities to democratize access to materials and resources

which were previously the exclusive domain of a few experts. When community

members have access to important documents from their own history, archiving,

scholarship, and community engagement can be brought together in a powerful

synthesis.

Abstract

Hay cientos de textos alfabéticos en lenguas zapotecas desde el siglo

dieciséis. No obstante, hoy en día los zapoteco-hablantes generalmente no pueden

leer estos textos, debido a una falta de acceso a los textos como también por

falta de familiaridad con las prácticas ortográficas. Además, la gramática ha

cambiado mucho en los siglos intermedios. Por consiguiente, muchos zapotecos no

tienen acceso a su historia escrita en su propia lengua. Ticha es un explorador

digital de texto que brinda acceso en línea a las imágenes, transcripciones,

análisis y traducciones de los textos en zapoteco colonial. El proyecto de Ticha

incluye talleres con miembros de la comunidad zapoteca como parte de un proceso

de desarrollo interactivo. Los comentarios y reacciones que resultan de estas

interacciones informan las decisiones del diseño para el proyecto. Aquí

analizamos y reflexionamos sobre la colaboración transnacional con los

“stakeholders” en la construcción de un proyecto digital

que indaga el uso del poder de las humanidades digitales para democratizar el

acceso a los materiales y recursos que previamente habían sido un dominio

exclusivo de unos pocos expertos. Cuando los miembros de la comunidad tienen

acceso a los documentos importantes de su propia historia, entonces el archivar,

la investigación, y el involucramiento con las comunidades pueden crear una

síntesis detonante.

Indigenous voices in colonial history

Around 1675, Sebastiana de Mendoza, a prominent woman in the Zapotec community of

Tlacochahuaya, Oaxaca, created her last will and testament [

Flores-Marcial 2015]

[

Munro et al. 2018]. In this document, she tells her descendants and

executors her wishes for the final disposition of her belongings. As

Flores-Marcial [

2015, 52] writes,

Sebastiana de Mendoza

bequeathed to her daughters, Gerónima

and Lorenza, and her granddaughter named Sebastiana, an array of belongings

that included religious paraphernalia, valuable agricultural goods, and

finished goods and money. She divided her property in the following manner:

ten magueys, a wool skirt, a cotton huipil, and ten pesos went to her

daughter Gerónima. She gave her granddaughter Sebastiana five magueys and a

picture of Saint Sebastian. She did not bequeath her house to anyone

specifically, but she gave her daughter Lorenza a total of thirty-five

magueys and declared that, as the oldest, she should be in charge of the

house and its affairs.

Sebastiana was careful to distribute her property, but also scrupulous in noting

her debts and obligations to others in the community as well as the debts and

obligations owed to her. This complex system of interconnected social and fiscal

responsibilities is known as

guelaguetza in Zapotec. In the

Zapotec inheritance system, her heirs inherited her

guelaguetza assets and liabilities. Her last will and

testament states:

chela tini pea nasaui quela queza

xtenia SanJuan que / lauia li chi lucas luis chi uitopa tomin lichi

Bartolo / me delos angel chi tomines lichi pedro no lasco chiui /

topatomines lichi Saluador mendoza toui peso lichi / pedro mendes chiui

topa tomines che la nosaui lorenso / garcia xonopeso pedro mendes no

sauini xopa peso no / saui rey mundo dela cruz cayopeso nosaui quetoo /

lorenso lopes chona peso — franco de agilar nosaui / ni chona peso

geroni moperes no sauini chona peso / quira tomin niri que gixeni caca

missa xteni qui / ropa leche lano

and I order [that] my guelaguetza is

owing [i.e., there is guelaguetza owing to me] in San

Juan Guelavía: in the house of Lucas Luis, twelve tomines; in the house of

Bartolomé de los Ángeles, ten tomines; in the house of Pedro Nolazco, twelve

tomines; in the house of Salvador Mendoza, one peso; in the house of Pedro

Méndez, twelve tomines; and Lorenzo García owes eight pesos; Pedro Méndez,

he owes six pesos; Reymundo de la Cruz owes five pesos; the late Lorenzo

López owes three pesos; Francisco de Aguilar, he owes three pesos; Gerónimo

Pérez, he owes three pesos. All this money they should pay, [that] will be

[for] masses for us two spouses. [Munro et al. 2018, 206–208, lines 42–53]

For an understanding of the social relationships and networks of colonial Oaxaca,

there are few sources as rich as testaments like that of Sebastiana de Mendoza.

Documents like these are of potential interest to many, particularly those with

personal and / or academic interests in the histories, cultures, and languages

of the Indigenous people of Mesoamerica. This document is of particular interest

to the Zapotec people of Tlacochahuaya. Yet this remarkable text — and many

others like it — are practically unknown to a large group of potential

readers.

Why have vital manuscripts like these not been accessible to members of

Indigenous communities who would like to read them? As we explain below, they

have mostly been held in physical archives where they are accessible primarily

to scholars with sufficient resources and privilege to use them. That these

archival resources are little known to Zapotec stakeholders aligns with the

analysis that “archives have functioned as mechanisms of

colonialism”

[

Gauthereau 2018]. For example, as pointed out by Stoler [

2002, 87], “What constitutes

the archive, what form it takes, and what systems of classification and

epistemology signal at specific times are (and reflect) critical features of

colonial politics and state power.” Ticha seeks to use the power of

digital humanities to democratize access to materials and resources which

previously were almost exclusively the domain of scholars. Archiving,

scholarship, and community engagement can be brought together in a powerful

synthesis when community members have access to important documents from their

own history.

Background and corpus

Zapotec is a language family indigenous to southern Mexico, and is the third

largest Indigenous language family in Mexico. Today, there are over 50 different

Zapotec languages, most endangered, spoken primarily in what is now the state of

Oaxaca, Mexico, by a total of approximately 450,000 people within a much larger

Zapotec ethnic community. The Zapotec language family, which belongs to the

Otomanguean stock, is on par with the Romance language family in terms of time

depth and diversity of member languages. The Zapotecs are one of the major

civilizations of Mesoamerica, with cultural traditions going back to 500 B.C.

and distinct from the better-known Nahua (Aztec) and Maya.

With the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, alphabetic writing was introduced and

adopted by Indigenous peoples. McDonough [

2014, 199] points out that, “as opposed to being

passive receivers of an imposed European technology, Nahuas have

appropriated and adapted alphabetic writing for their own purposes.”

The same can be said of speakers of Zapotec, who quickly put this new technology

to use. Zapotec has one of the longest records of alphabetic written documents

for any Indigenous language of the Americas [

Romero Frizzi 2003]. Over

900 documents in Zapotec language written by Zapotec scribes have been

identified, the earliest from 1565 [

Oudijk 2008, 230]. The

richest variety of colonial Zapotec documents are those composed in the kind of

Zapotec spoken in and around Oaxaca City, known as Valley Zapotec. The Colonial

Valley Zapotec corpus includes an extensive dictionary [

Cordova 1578b], grammar [

Cordova 1578a], and

doctrine [

Feria 1567], and over 200 administrative documents

(mostly wills).

These documents hold invaluable information for a wide range of interested

parties. They provide insight into the ethnic diversity, religious history, and

familial, social, and economic structures of Mexico for a 500-year period. They

create a bridge across multiple cultural borders: a link between modern

scholars, colonial priests, and Zapotec people throughout time. The large corpus

of Colonial Nahuatl language material has proven useful to scholars across many

disciplines (e.g. [

Lockhart 1992]; [

Madajczak and Hansen 2016];

[

Matthew and Bannister 2020]). As Colonial Zapotec is less studied and is

understood by far fewer people, linguistic analysis is particularly needed to

help users understand the texts and to allow them to critically evaluate any

translations of the original text. Because of the difficulty in using the

original manuscripts and in understanding the language, this corpus of documents

written in Colonial Valley Zapotec has not been easily accessible outside of a

small circle of specialists [

Broadwell and Lillehaugen 2013].

Difficulties of access to colonial materials

Reading and translating these Colonial Valley Zapotec documents can be extremely

difficult. Physical access alone can be a barrier to reading the documents, as

these texts are housed in various archives not only throughout Oaxaca and other

parts of Mexico, but also in archives in the United States and Europe. One must

know which archive to visit and how to request a document, and sometimes that is

insufficient. For example, the Archivo General del Poder Ejecutivo del Estado de

Oaxaca has changed their archival numbering system, and now reference numbers

like those published in Smith Stark et al. (

2008) are no longer accurate. Moreover, discrimination against people

perceived to be Indigenous means that some employees at an archive, including

guards, may discourage and intimidate some potential users from entering the

archives, as we have ourselves witnessed on more than one occasion.

Even if one has physical access to the texts, many aspects of the documents

themselves can be a barrier to access. The writing and printing conventions for

colonial documents can be opaque to contemporary users. Reading handwriting from

this period often requires special training, and printed texts often use

extensive abbreviations and may also contain printing errors (such as reversed

letters and broken type) and handwritten corrections.

The Zapotec language poses additional challenges in understanding the texts.

Knowledge of (or fluency in) a modern Zapotec language is not enough to

translate the colonial documents due to variation in orthographic choices and

regular processes of language change. The orthography in the texts is highly

variable and inconsistent throughout the corpus, and there is as of yet no fully

adequate Zapotec-to-Spanish or Zapotec-to-English dictionary that reflects the

full range of orthographic variation found in the corpus [

Broadwell and Lillehaugen 2013]. Beyond orthography, the Zapotec language has

undergone language change over the last 500 years, including significant

phonological and morphosyntactic alterations. Thus the grammar of these

documents is also different from that of modern Zapotec languages. Potential

users of such documents cannot read them without training, and, as a result,

only a very small number of people use them — typically linguists and

ethnohistorians with special interest in Zapotec language materials and a

handful of other dedicated specialists. Other stakeholders, including most

speakers of modern Zapotec languages, have no easy way to discover or read the

texts that document the histories of their communities.

In addition to these more tangible obstacles, discriminatory linguistic

ideologies pose systemic challenges to the access of Zapotec language materials.

In Mexico, Zapotec is viewed as something less than a real language, and

knowledge of Zapotec language is devalued. There are pervasive false beliefs

that Zapotec has never been written, cannot be written, and perhaps even should

not be written. Janet Chávez Santiago, a native Zapotec speaker and language

activist, reflects (in English) on the impact of such beliefs:

When I was in elementary school in the 90s, I remember children

speaking Zapotec in many contexts: playing in the streets, at parties, and

during town celebrations — but never at school. Instead, we had to

“behave” ourselves by not speaking Zapotec, otherwise

teachers could punish us by giving us extra homework or by not letting us

eat lunch or even beating us. Teachers made us believe that speaking Zapotec

was disrespectful, something to be ashamed of. They devalued our language by

calling it a “dialect”. As a child, I never saw anything

written in Zapotec. All my books and books that my parents bought me were in

Spanish, so at some point I thought teachers were right, that Zapotec was a

language with no value so nobody wanted to write books in my language. By

the end of the 90s there was no need to prohibit children speaking Zapotec

in the school, because in order to avoid their children being punished,

parents had switched to speaking in Spanish to their children at home. These

days, there are very few children who speak Zapotec in my town. [Mannix et al. 2016]

These ideologies about the value of Zapotec language certainly impact access in

multiple ways, but they also create a space for projects such as ours to

intervene in larger questions of social justice. In the following sections we

describe how Ticha addresses inequities of access in an effort to make the

Colonial Valley Zapotec corpus available to the widest possible audiences.

Moreover, we discuss how the creation and evolution of Ticha is done in

consultation and collaboration with Zapotec-speaking community members such that

both the methodology and “result” are spaces for

collaboration with stake-holding community members. We consider how creating

access to a corpus of historical texts in Valley Zapotec can be a form of

resistance to such false ideologies, both in its form as a resource and through

the collaborative methods in which we create and grow the project.

The Ticha project

Ticha (

https://ticha.haverford.edu) is a large, collaborative,

interdisciplinary digital resource [

Lillehaugen et al. 2016], with a

diverse team, including linguists, ethnohistorians, digital scholarship experts,

and Zapotec language and culture experts.

[1] The core team

consists of academics and non-academics as well as Zapotec people and non-Native

people. Undergraduate research assistants play a large role in the development

of the project, as discussed below.

[2] Beyond these more formalized team members, there is

broader community participation through crowd-sourced transcription and

commenting, some by anonymous participants and others credited on the

acknowledgements page of Ticha.

The Ticha project seeks to provide access to the corpus and language of the

Colonial Valley Zapotec corpus in a way that mitigates the systemic language

devalorization described above. In regards to the corpus itself, we practice

post-custodial archiving [

Ham 1981]

[

Cook 1994], using existing digital images of the documents when

available, and by creating our own high-resolution digital images when not. As

Alpert-Abrams points out, “In the United States, we have a

long history of removing historical records from the communities that

created them, often in the name of preservation… The post-custodial model of

archival practice uses digital technology in pursuit of a more collaborative

approach to multinational archival work” [

2018, n.p.]. Post-custodial practices are

usually discussed in relation to institutions that are capable of taking

possession of materials — like libraries and archives. Ticha is not a library or

a physical archive, nor is it an institution that seeks to assume possession of

archival texts. The creation of digital surrogates and the maintenance of

collaborative partnerships with stake-holding communities allow us, however, to

curate a collection of texts digitally.

The Ticha interface, built in the Django framework, allows users to browse and

search the corpus of Colonial Valley Zapotec texts, including the images and

metadata. Given the sociolinguistic context around this language and these

texts, we make any resources we have available as soon as possible, borrowing

from the idea of progressive archiving [

Nathan 2013]. This means

that for some texts, we may just have images and metadata. For others we may

have first pass transcriptions. Yet others may have polished transcriptions and

translations. We invite corrections and collaboration and view the resource as a

living document and a space for collaboration.

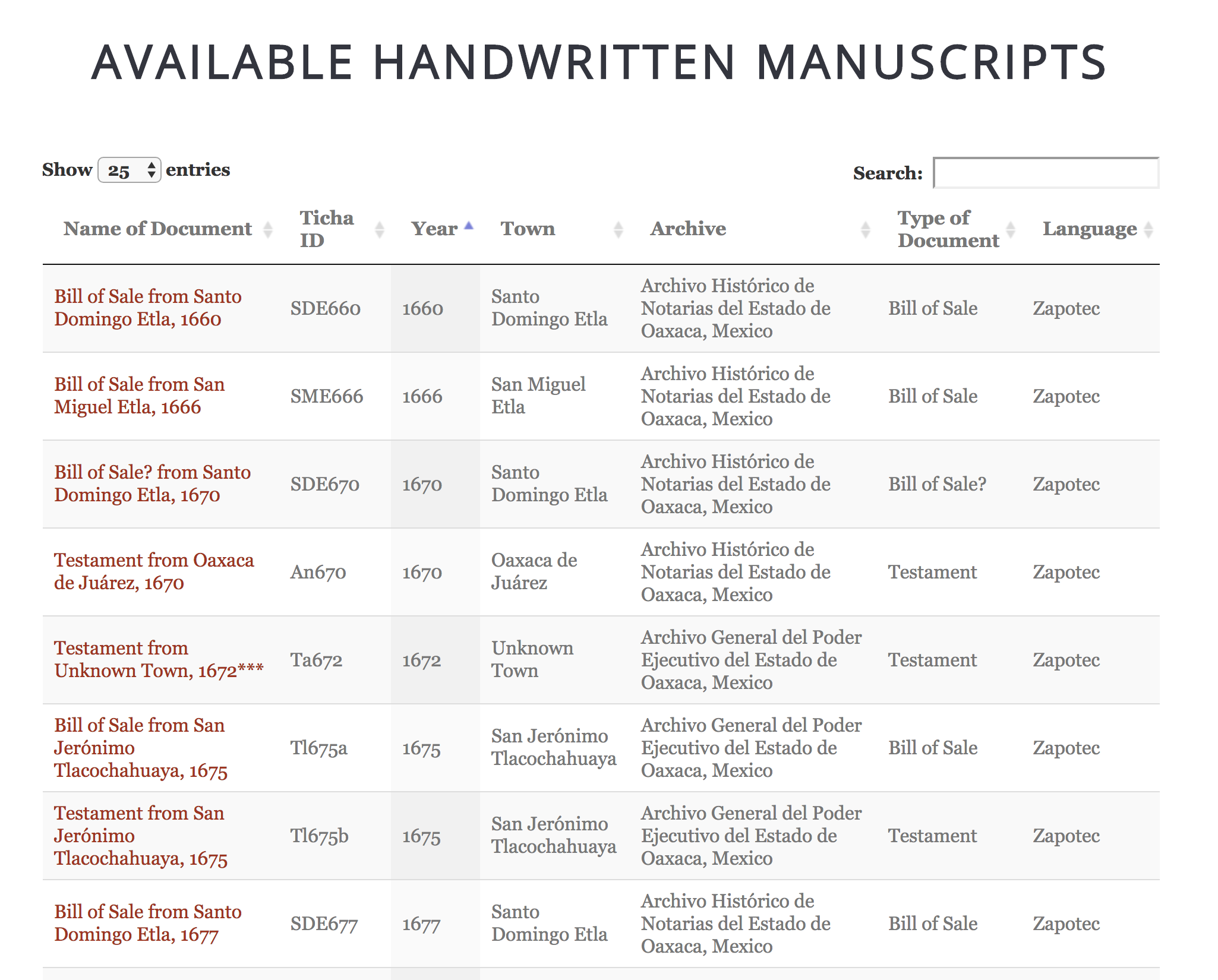

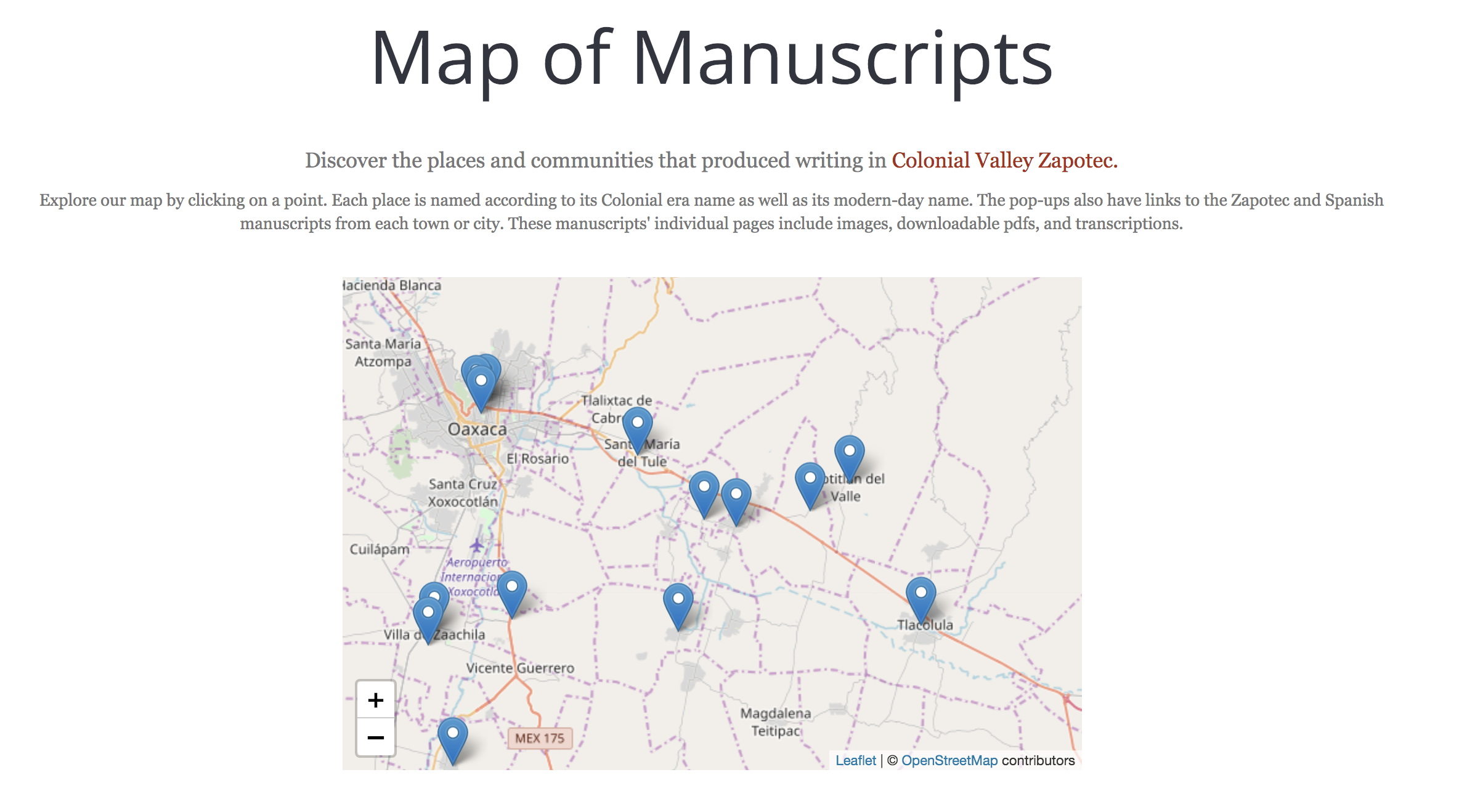

Ticha allows users to navigate a corpus that is otherwise physically dispersed.

Figure 1 illustrates one interface for browsing the corpus, which can be

searched or filtered along several fields, including date of document, town of

origin, archival home, genre, and language of the text. The corpus can also be

navigated through a timeline and a map, the latter of which is shown in Figure

2.

In order to make Ticha more accessible to a wide range of users, we present the

texts not as flat objects but as dynamic resources. Other scholars have

published translations and annotations of colonial-era linguistic materials in

print form; Lockhart’s translation of a Colonial Nahuatl grammar is a notable

example [

Carochi and Lockhart 2001]. However, print editions are generally

aimed at academic audiences and often present readers with too much detail for

the interested non-academic. Presenting this material as a digital resource

allows readers to view or hide different levels of analysis, depending on their

needs and interests.

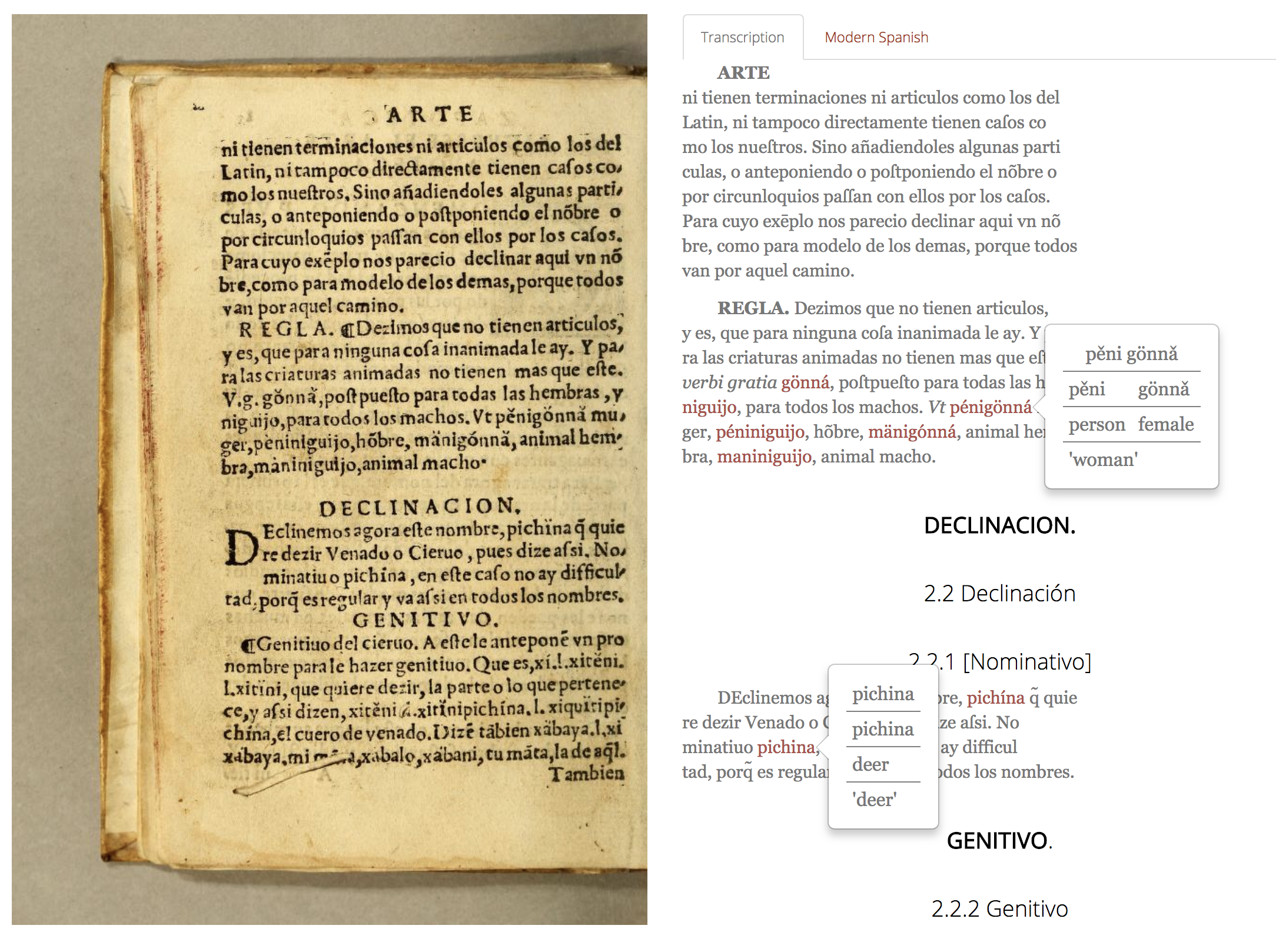

Figure 3 shows a page from the

Arte en lengua

zapoteca, a colonial-era grammar of Valley Zapotec which is credited

to Fray Juan de Cordova, though undoubtedly many (uncredited) Zapotec

individuals were involved in its creation [

Cordova 1578a]. At the

most basic level, visitors may view the scanned images of the original document

side-by-side with a diplomatic transcription. As the colonial Spanish text

contains abbreviations and spelling inconsistencies which may be difficult for

some users to understand, a modernized Spanish version is also available. This

was created in response to a request from Zapotec community members who noted

that the Early Modern Spanish was a barrier to understanding the text. The

modernized Spanish version updates spelling and word boundaries, but does not

alter lexical choice or syntax. Feedback from speakers of modern Mexican Spanish

has been clear that this type of modernization has been helpful in reading the

text.

Layers of accessible linguistic information are also used to communicate more

about the Zapotec language in these texts. As the Arte is a meta-linguistic document, the text itself is an analysis

of the Zapotec language. As is to be expected from the time period, this grammar

is structured following the Latin model. For example, in the passage in Figure 2

describes the “declensions” of Zapotec nouns, a concept that

only serves to obscure the grammar of Valley Zapotec, which has no grammatical

case. While the framework is rather unhelpful in understanding the language, the

Zapotec language examples themselves are invaluable. Ticha can facilitate

accessibility to understanding the Zapotec here, by providing access to modern

linguists’ understanding of the Zapotec language. As shown in Figure 2, clicking

on a Zapotec word or phrase in the text brings up a pop-up containing a complete

morphological analysis and translation of the Zapotec, which may or may not be

consistent with the explanation in the original text. The interested reader,

then, can compare the analysis in the Arte with

that of a modern linguist.

As we considered what kind of access and collaboration could mitigate the type of

language devalorization described above, we also wanted to be careful that a

project on a historical corpus of Zapotec texts did not reinforce another

harmful false ideology — that Zapotec language and people are only of the past,

frozen in time. This type of thinking regarding Indigenous people, culture, and

language is ubiquitous. We wanted Zapotec people and modern language to be

clearly visible in the Ticha Project.

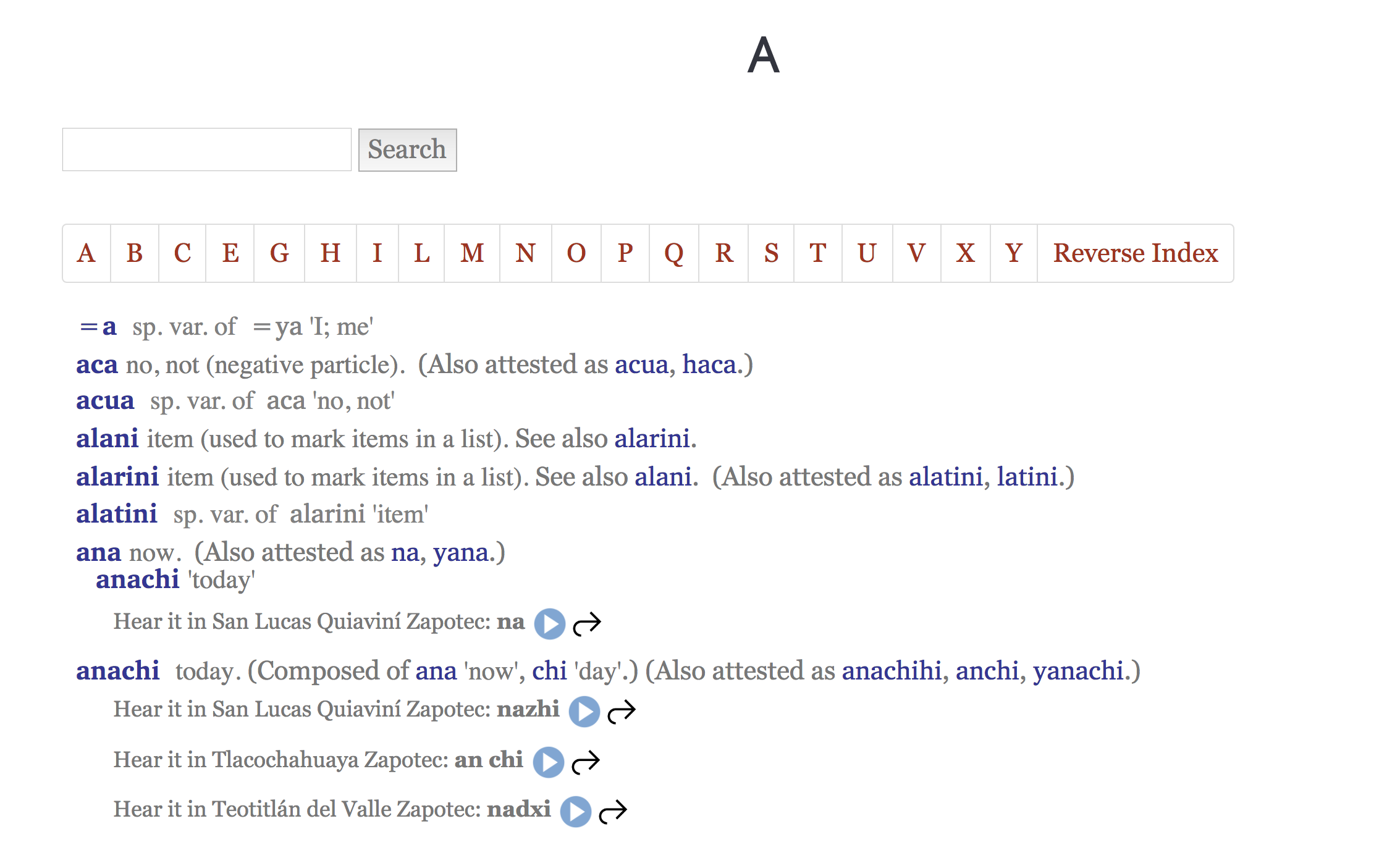

One way we addressed this was by bringing Zapotec voices to the site. Figure 4

shows one of the resources available on Ticha: a vocabulary of the most common

words found in the corpus, along with their definitions and alternative

spellings. Wherever possible, we connect these lexical entries for historical

forms of words with their modern counterparts, by linking entries in Ticha’s

Vocabulary with entries in online Talking Dictionaries for several Valley

Zapotec language varieties (described in [

Harrison et al. 2019]),

including those from Teotitlán del Valle [

Lillehaugen and Chávez, et al. 2019],

San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya [

Lillehaugen and García Guzmán, et al. 2019], and San Lucas

Quiaviní [

Lillehaugen et al. 2019]. The design came out of one of the

in-person workshops in Oaxaca. As the room full of Zapotec speakers from

different communities in the Valley of Oaxaca worked through understanding one

of the colonial-era texts together, a pattern of practice emerged. For each

word, speakers would go around the table, saying the modern cognate in their

variety of Zapotec. The text was read, performed — even echoed — in a multitude

of modern Zapotec languages. The Vocabulary on Ticha is our attempt to realize

this in a digital format.

Connecting these modern lexical resources with this historical vocabulary not

only allowed us to resist a reading of these materials that excludes the modern

Zapotec community, but also allowed us to incorporate a Zapotec designed

engagement with the texts. As described further in the section that follows, our

iterative methodology includes regular trips to Oaxaca, where we not only

solicit feedback and suggestions from Zapotec speakers with interest in the

corpus but also spend time looking at Colonial Zapotec language texts

together.

Digital scholarship and community engagement

In this section, we turn to directly examining the structure and methodology

surrounding our development process, and in particular the role of stakeholding

communities in our project design. Thorpe and Galassi note that long-term

engagement with stakeholding communities requires libraries to challenge their

traditional workflows and “establish new ways of practice

that allow Indigenous people and communities to guide and control the

process” [

2014, 91–92]. These ideas

are echoed in the literature on community-based linguistic research, where

scholars have recently emphasized community collaboration and sharing control of

research project design [

Czaykowska-Higgins 2009]

[

Rice 2011]. Ticha prioritizes community engaged methods not only

as a goal, but as a means throughout the project; as Ortega notes in her review

of Ticha, “the engaging of a community of Zapotec speakers

is very clearly the backbone of the project and, through recurrent

workshops, has given shape to its other components” [

2019].

Our project benefits from other digital scholarship projects working with

Indigenous languages, corpora of manuscripts, and community engaged projects

generally, especially those working with marginalized communities and languages.

We are aware of one other project that also makes Zapotec language texts

publicly accessible: Satnu: Repositorio Filológico Mesoamericano (

https://satnu.mx/), which as the name

suggests is a repository and digital archive for texts in Mesoamerican

languages, including — but not limited to — Zapotec language texts. The Early

Nahuatl Library (

http://enl.uoregon.edu/), for example, gathers together 16th- through

19th-century Nahuatl-language manuscripts with transcriptions, translations, and

historical context. In this issue, Matthew and Bannister describe NECA:

Nahuatl/Nawat in Central America (

https://nahuatl-nawat.org/), a digital project that makes a corpus of

Nahuan-language documents produced in Spanish Central America publicly

available. Olko (2019) describes a community-engaged approach in which archival

work on Nahuatl language texts is fused with ethnolinguistic fieldwork in a

project that seeks to “combine Western/academic and

Indigenous methodologies” [

2019, 7].

Moving beyond Nahuatl, the Proyecto Oralidad Modernidad (

https://oralidadmodernidad.wixsite.com/oralidad) uses a

community-engaged approach to language documentation that encourages Indigenous

Ecuadorians to connect with their history through language as they document the

knowledge of elders [

Haboud 2019]. Far outside of Latin America,

The Notebooks of William Dawes (

https://www.williamdawes.org/; [

Nathan et al. 2007]) makes

accessible threatened language documentation from the century on Darug/Dharuk, a

language of Sydney, Australia, through images, transcriptions, and connections

to modern speakers. Originally located at the SOAS and now a free-standing

resource, the Notebooks of William Dawes brings archival texts, commentary, and

modern language together online and through a companion print version [

Nathan et al. 2009]. Ticha combines elements of many of these projects —

and especially that of the Notebook of William Dawes — connecting stakeholding

communities to Zapotec history through colonial-era documents while

acknowledging and engaging with the social-political power of Zapotec writing,

spoken Zapotec language, and Zapotec communities.

Ticha extends the traditional user-centered approach to design by defining user

groups as communities. Each community brings its own skill sets and experiences

to the project, which shapes the technology and workflows that make up the

project. The array of communities that make up Ticha include the Zapotec

community members, Haverford College linguistics and computer science students,

scholars in linguistics and ethnohistory, and librarians, though membership in

these categories may overlap. Each community is both a user and a participant in

their engagement with the project web site. Access to the materials includes

traditional methods of discovery, but also engagement with and close reading of

the materials through features like transcription, text encoding, and audio

recording. The artifacts of this engagement become part of the Ticha workflow

(e.g. manuscripts transcribed by Zapotec community members or Haverford

linguistics students, recordings for the Talking Dictionary by Zapotec community

members, or morphological analysis of Zapotec words by linguists), and emerge as

additional points of engagement for the project’s communities. As such, the

design of the project accounts for the experiences and needs of each community,

is informed by feedback from its communities, and is iterative in its approach.

The morphological analysis is done in Fieldworks Language Explorer (FLEx), and

discussed in

Broadwell and Lillehaugen, 2013.

This is exported as XML and processed with the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative)

encoding of the text by a Python script and XSLT (Extensible Stylesheet Language

Transformations) to ultimately produce HTML. This HTML creates the public-facing

interface for the encoded texts.

Our development process has a clear institutional component, as Haverford College

Libraries is an active partner in the design and development of the Ticha

project site. The Digital Scholarship group, which partners with faculty and

students to produce multimodal scholarship through the use of digital tools and

methods, has been primarily responsible for web design, web and application

development, server administration, archival and preservation workflows, and

data curation practices for the project.

Ticha is a system of tools that fit together in ways that meet the needs of its

community members. The skill sets and tools available to each community

determines the choices of tools and methods for the project. While the library

is responsible for technical development of the project site, digital

scholarship librarians and student employees are often developing tools or

features for the first time. The library exercises a strong preference for

existing tools that meet community needs and standards and prefers to develop

custom-made solutions only when the project exceeds the capacity of ready-built

tools. The ability to export data in standard formats (e.g. JSON, CSV, XML) is

essential for each tool so that future flexibility is built into the project in

all areas.

Existing tools come with their own set of limitations, as they are not developed

in the context of a specific project but instead designed to be used broadly.

When the needs of a community reach beyond the limits of — or are not being

effectively met by — existing tools, it is necessary to built upon existing

project features. An open channel for feedback is crucial, and that feedback

drives iteration on the features that require it. Feedback comes in two primary

forms: workshops and web analytics. Web analytics (Ticha uses Google Analytics)

provide meaningful data on site usage and user location, from which we can draw

useful conclusions. For example, analytics in late 2017 suggested that users

that visited the home page of the project site often moved on quickly, while

those who visited specific manuscripts directly (from a link shared on social

media or search results) tended to engage with other areas of the site. This

data strongly suggested that a redesign of the home page was necessary to

provide users with more information on what they can do in the Ticha project

site, and such a redesign was implemented during the summer of 2018.

Some of the most meaningful feedback comes from engagement with members of the

Zapotec-speaking community in Oaxaca. Transcription workshops helped the project

team see the tools in action on the equipment available to its users (i.e.

tablets or computers that aren’t necessarily current, running the latest

software, or reliably connected to the Internet). A series of workshops with

students at the Centro de Estudios Tecnológicos Industrial y de Servicios No.

124 (CETIs #124), a high school in Tlacolula de Matamoros, Oaxaca, was

significantly affected by Wifi connectivity issues, highlighting the need to

account for access to the manuscripts and some features of the project site when

the network connection is unreliable. As a result, the project now features a

PDF export option for manuscripts that include high-resolution images of the

documents and associated metadata that can be saved to a storage device for

offline access.

The transcription feature for the manuscripts on Ticha is a particularly

instructive case study of this iterative approach. In 2015, members of the

Zapotec-speaking community expressed a strong desire to transcribe the

manuscripts through the project site. While the Haverford College Libraries

could have attempted to build a custom transcription interface, the Digital

Scholarship team did not have technical capacity to develop such a feature. The

project was already using Omeka as a digital collections platform to serve and

describe the digitized manuscripts in parallel with the Django project site. The

Scripto plugin for Omeka provided a ready-built solution for a transcription

feature. Implementation of that feature occurred in the spring of 2016, at which

point the project group conducted two workshops with Zapotec-speaking community

members in Oaxaca on document transcription. During these workshops, the

affordances and limitations of the Scripto interface became apparent. Users of

the web site needed to perform three or four clicks to move from the manuscript

viewer to the transcription tool, and the interface itself was difficult to

customize for language and format. With this feedback, the digital scholarship

group developed its own transcription interface in parallel with the

already-launched Scripto interface, which then replaced Scripto in the spring of

2018. The new transcriber is completely integrated within the existing

manuscript viewer interface, accessible by only one click or tap from an input

device.

An interest on the part of academics and/or community members to contribute to

online transcriptions and translations should not be assumed, as demonstrated in

the context of NECA (Nahuatl/Nawat in Central America) in

Matthew and Bannister, this issue, who also

express encountering similar limitations with Scripto in their project.

Impact and reflections

As part of our commitment to community-led research, Ticha includes an advisory

board of Zapotec community members. While community workshops provide feedback

on the functionality of the site, members of the advisory board give ongoing

advice to shape the project as a whole. In this section, Moisés García Guzmán

and Dr. Felipe H. Lopez, two members of the advisory board, reflect on the

impact of Ticha in their community. Their words speak best for themselves and

thus are intentionally presented here as they were written by the co-authors.

García Guzmán, a Zapotec educator and activist, offers the following reflection:

Many local communities in Oaxaca were not aware of the

existence of documents in Zapotec. Ticha has helped them to see how

important their language was in official procedures in the past, but has

also helped to create a link with revitalization efforts that are going on,

by showing community members that their proposals on contemporary Zapotec

can lead to a new standardized written system. García Guzmán, a Zapotec

educator and activist, offers the following reflection:

As a speaker and activist in my community, Ticha is a great

tool in raising awareness on all revitalization efforts. Young kids can see

how our language played an important role in some activities of our towns in

the past. But also I encourage them not to see the language as only a part

of our past, but to also work towards restoring use of our language in many

contexts where Zapotec seems to be losing ground. In the end, I hope to

instill in them the idea to work towards an official recognition again. I

also hope that our efforts will encourage local authorities to give us

better access to archives, by showing them all the work that is done. The

existence of Ticha makes archival authorities more open and cooperative with

these efforts.

Overall, it has been a great experience, and as the work

progresses, it helps students, speakers and communities to strengthen the

sense of identity with our native language.

Lopez has been key in starting and facilitating the workshops at the high school

in Tlacolula. He offers these reflections:

I have always

believed that the youth could be very influential in their communities today

and have sought ways to engage with them to promote the Zapotec languages in

their pueblos. For the last three years I have had the opportunity to

participate in Zapotec workshops at CETIs #124 in collaboration with

Haverford College and the Ticha project. These workshops have become pivotal

for engaging with students and school officials to rethink the value and

importance of Zapotec. In a sense, these workshops have given this school

community a different access to the language. In these three years, I have

witnessed the way the students involved in these workshops have strengthened

their values towards their own language at the same time their

identities.

At the beginning there was some skepticism about these

Zapotec workshops given that only six students participated. However, each

year there has been an increase in the number of students participating, and

last year there were more than 20 students who signed up for the Colonial

Zapotec workshops.

This particular workshop gave students an opportunity to

understand their language from a historical perspective and to work with

Colonial documents. The Zapotec students tried to understand Colonial

Zapotec words and to think about the equivalent modern Zapotec words.

Through these documents, they understood that Zapotec is a living language

which has been written for hundreds of years, dispelling the notion that

Zapotec is not a written language. All the students found commonalities

between Colonial Zapotec and the various Zapotec languages they spoke.

Furthermore, they were pleasantly surprised to learn ways to count in

Zapotec. As is the case in my own community of San Lucas Quiaviní, most

students can only count up to ten or so and then use Spanish words, and so

through these Colonial Zapotec documents they learned something about their

own language.

The openness of the Principal Dr. Marcos Pereyra Rito and

the support of the main advocate of this program, Abisai Aparicio, has given

this opportunity to students, despite the absence of a clear precedent in

the educational system in Mexico. In fact, historically, schools served as

an instrument of assimilation and punished people who spoke their Indigenous

language. However, as part of this collaboration at CETIs #124, the

vice-principal, who isn’t a native speaker of Zapotec, made an effort to

read a message in Zapotec to the participating students in the workshop last

year. Also, one of the teachers, Dr. David Velasco, was willing to accept

work written in Zapotec in his literature course. I have also witnessed how

students have changed their behaviour towards using their language since

these workshops have started. I see students talking Zapotec more openly on

campus, whereas prior to this project, we were told that students were

embarrassed to speak Zapotec on campus or even to admit they spoke it at

all. So, the conditions in which these students decide to use their language

is being reshaped at this institution, hopefully as well as outside. These

efforts, then, are working to reshape the sociolinguistic possibilities at

this institution, and potentially even beyond.

Conclusions

As Nakata and Langton say, effective community collaboration is not just

“consultation” with the community, but “dialogue, conversation, education, and working through things

together” [

2005, 5]. Ticha embraces

this philosophy by working through an ongoing conversation with user

communities. Our iterative approach allows the technical design of the project

to continually meet the needs of its communities. Furthermore, it situates the

project in dialogue with other digital projects that employ similar tools or

methods, and provides a model for doing truly community-engaged digital

scholarship. For example, Albert-Abrams et al. describe their work as being

practiced “not through a static set of methodologies, but

rather an ongoing process of learning, unlearning, and restructuring in

pursuit of a collective good” [

2019, 1]. We recognize our own practice in this description, as well

as in the framing provided by Duff et al, that “Social

justice is always a process and can never be fully achieved” [

2013, 324].

Our engagement with the Ticha project has yielded many positive results, both for

scholars and members of the Zapotec community. The Zapotec language documents in

Ticha are a resource for those interested in Zapotec people, their languages,

and their history. Ticha’s project design is grounded in well-established

theories of cultural and linguistic reclamation and revitalization. Scholars

have long discussed the importance of schools in creating positive language

ideologies, particularly among youth [

Lee 2007], as well as the

complexity surrounding the roles that Indigenous educators can have within these

systems, in particular in Mexico [

McDonough 2014, 160].

Researchers have also noted the power of Indigenous community members directly

preserving their own histories [

Hoobler 2006]. Given this, we

think it is likely that similar results might be achieved in other communities

following our methods, adapted for local priorities and practices. While a

handful of projects exist, as mentioned earlier, we could imagine even more

projects like this not only in Oaxaca, but in Latin America more broadly, and

world-wide where such historical corpora exist. All of the Ticha encoding and

scripting is freely available to anyone who would like to use or adapt it for

similar projects.

As local language ideologies in Mexico favor Spanish over Indigenous languages

such as Zapotec, a project like Ticha serves as a resource for local language

activists. In particular, Ticha forefronts Indigenous voices and knowledge. As

Pratt says: “If one studies only what the Europeans saw and

said, one reproduces the monopoly on knowledge and interpretation that the

imperial enterprise sought” [

2007, 7].

Important historical documents, like the testament of Sebastiana de Mendoza,

demonstrate in a very concrete way the long literate history of Zapotec people

and the importance of the Zapotec language to understanding this history.

We also take this project to be a clear demonstration of the power of digital

humanities projects to democratize access to materials and resources which might

otherwise be used primarily by scholars. We seek to practice transformational

work as part of a larger interdisciplinary project that we would also classify

as engaged scholarship. When community members have access to important

documents from their own history, we are able to bring together archiving,

scholarship, and community engagement in a powerful synthesis.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge our appreciation to the editors Hannah Alpert-Abrams and

Clayton McCarl for all their work in making this issue possible, including their

advice in the development of this piece. Thanks also to two anonymous reviewers

for the helpful and encouraging feedback and to K. David Harrison and Peter

Austin for their thoughtful suggestions. We are grateful for comments from

attendees at the following conferences: the annual meeting of the Latin American

Studies Association, Encuentro de Humanistas Digitales, and the Coloquio sobre

Lenguas Otomangues y Vecinas. In addition, we thank Julie Gonzales and Eloise

Kadlecek for their editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Special thanks for K. David Harrison and Jeremy Fahringer in facilitating the

connection between the Zapotec Talking Dictionaries and Ticha’s Vocabulary.

The Ticha project is grateful to funding from the American Council of Learned

Societies, the American Philosophical Society, the Center for Peace and Global

Citizenship at Haverford College, the Provost Office of Haverford College, the

Hurford Center for the Arts and Humanities at Haverford College, the Haverford

College Libraries, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Tri-Co

Digital Humanities. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations

expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National

Endowment for the Humanities.

Works Cited

Alpert-Abrams et al. 2019 Alpert-Abrams, H.,

Bliss, D. A., and Carbajal, I. “Post-Custodialism for the

Collective Good: Examining Neoliberalism in US-Latin American Archival

Partnerships.” In M. Cifor and J. A. Lee (eds.),

Evidences, Implications, and Critical Interrogations of Neoliberalism in

Information Studies, special issue

Journal of

Critical Library and Information Studies 2.1 (2019). doi:

10.24242/jclis.v2i1.87.

Broadwell and Lillehaugen 2013 Broadwell, G.A.

and Lillehaugen, B.D. “Considerations in the creation of an

electronic database for Colonial Valley Zapotec,”

International Journal of the Linguistic Association of the

Southwest, 32 (2013): 77–110.

Carochi and Lockhart 2001 Carochi, H., and

Lockhart, J. (trans.). Grammar of the Mexican Language:

With an Explanation of Its Adverbs. Stanford University Press,

Stanford (2001).

Certeau 1988 [1974] de Certeau, M. “The Historiographic Operation (1974),” in The Writing of History. Columbia University Press, New

York (1988).

Cook 1994 Cook, T. “Electronic

Records, Paper Minds: The Revolution in Information Management and Archives

in the Post-Custodial and Post-Modernist Era,”

Archives and Manuscripts 22 (1994): 300–328.

Cordova 1578a Cordova, Fr. J. de. Arte en lengua zapoteca [Grammar in the Zapotec

language]. En casa de Pedro Balli, Mexico (1578).

Cordova 1578b Cordova, Fr. J. de. Vocabulario en lengua çapoteca [Vocabulary in the

Zapotec language]. Ediciones Toledo, Mexico (1578/1987).

Czaykowska-Higgins 2009 Czaykowska-Higgins, E.

“Research Models, Community Engagement, and Linguistic

Fieldwork: Reflections on Working within Canadian Indigenous

Communities,”

Language Documentation and Conservation, 3.1

(2009): 15–50.

Duff et al. 2013 Duff, W. M., Flinn, A., Suurtamm,

K. E., and Wallace, D. A. “Social justice impact of

archives: a preliminary investigation.”

Archival Science, 13 (2013): 317–348.

Feria 1567 Feria, Fr. P. de. Doctrina cristiana en lengua castellana y çapoteca

[Christian doctrine in the Spanish and Zapotec languages]. En casa de Pedro

Ocharte, Mexico City (1567).

Flores-Marcial 2015 Flores-Marcial, X.M.

A history of guelaguetza in Zapotec

communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th century to the

present. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los

Angeles, United States (2015). Retrieved from

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tv1p1rr.

Haboud 2019 Haboud, M. “Estudios sociolingüísticos y prácticas comunitarias para la documentación

activa y el reencuentro con las lenguas indígenas del Ecuador,”

Visitas Al Patio 13 (2019): 37–60.

Ham 1981 Ham, G. “Archival

Strategies for the Post-Custodial Era,”

The American Archivist 44.3 (1981): 207–216.

Harrison et al. 2019 Harrison, K. D.,

Lillehaugen, B. D., Fahringer, J., and Lopez, F. H. “Zapotec

language activism and Talking Dictionaries. Electronic lexicography in the

21st century.” In I. Kosem, T. Zingano Kuhn, M. Correla, J. P.

Ferreria, M. Jansen, I. Pereira, J. Kallas, M. Jakubíček, S. Krek, and C.

Tiberius (eds.),

Electronic lexicography in the 21st

century. Proceedings of the eLex 2019 conference (2019), 31–50.

https://elex.link/elex2019/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/eLex_2019_3.pdf.

Hoobler 2006 Hoobler, E. “‘To Take Their Heritage in Their Hands’: Indigenous

Self-Representation and Decolonization in the Community Museums of Oaxaca,

Mexico,”

American Indian Quarterly 30 (2006):

441–460.

Lee 2007 Lee, T. “‘If They Want

Navajo to Be Learned, Then They Should Require It in All Schools’:

Navajo Teenagers’ Experiences, Choices, and Demands Regarding Navajo

Language,”

Wicazo Sa Review 22 (2007): 7–33.

Lillehaugen and García Guzmán, et al. 2019 Lillehaugen,

B.D., and García Guzmán, M., with Goldberg, K., Méndez Morales, M.M., Paul, B.,

Plumb, M.H., Reyes, C., Williamson, C.G., and Harrison, K.D.

Tlacochahuaya Zapotec Talking Dictionary, version 2.1.

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages (2019).

http://www.talkingdictionary.org/tlacochahuaya.

Lillehaugen and Chávez, et al. 2019 Lillehaugen, B.D. and Chávez Santiago, J., with Freemond, A., Kelso, N.,

Metzger, J., Riestenberg, K., and Harrison, K.D.

Teotitlán

del Valle Zapotec Talking Dictionary, version 2.0. Living Tongues

Institute for Endangered Languages (2019).

http://www.talkingdictionary.org/teotitlan.

Lillehaugen et al. 2016 Lillehaugen, B.D.,

Broadwell, G.A., Oudijk, M.R., Allen, L., Plumb, M.H., and Zarafonetis, M.

Ticha: a digital text explorer for Colonial Zapotec,

first edition (2016). Online:

http://ticha.haverford.edu/.

Lillehaugen et al. 2019 Lillehaugen, B.D.,

Lopez, F.H., and Munro, P., with Deo, S.M., Mauro, G., and Ontiveros, S.

San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec Talking Dictionary, version

2.0. Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages (2019).

http://www.talkingdictionary.org/sanlucasquiavini.

Lockhart 1992 Lockhart, J.

The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural

History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth

Centuries. Stanford University Press, Stanford (1992).

Madajczak and Hansen 2016 Madajczak, J and

Hansen, M.P. “Teotamachilizti: an analysis of the language

in a Nahua sermon from colonial Guatemala,”

Colonial Latin American Review 25 (2016):

220–244.

Mannix et al. 2016 Mannix, A., Lillehaugen, B.D.,

and Chávez Santiago, J. “Technology and collaboration in

language documentation and revitalization: The case of a Zapotec Talking

Dictionary,”

4th International Conference on Language Documentation and

Conservation, Honolulu (2015, February). Online:

https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/25320.

Matthew and Bannister 2020 Matthew, L. and

Bannister, M. “The Form of the Content: Nahuatl/Nawat in

Central America (NECA),”

Digital Humanities Quarterly, this issue

(2020).

McDonough 2014 McDonough, K. S. The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Post-conquest

Mexico. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson (2014).

Munro et al. 1999 Munro, P. and

Lopez, F.H., with Mendez, O., Garcia, R., and Galant, M.R. Di’csyonaary x:tèe’n dìi'zh sah San Lu’uc. San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec

dictionary. Chicano Studies Research Center, UCLA, Los Angeles

(1999).

Munro et al. 2018 Munro, P., Terraciano, K.,

Galant, M., Lillehaugen, B.D., Flores-Marcial, X., Ornelas, M., Sonnenschein,

A.H., and Sousa, L. “The Zapotec language testament of

Sebastiana de Mendoza, c. 1675,”

Tlalocan 13 (2018): 187–211. Online:

https://revistas-filologicas.unam.mx/tlalocan/index.php/tl/article/view/480/458.

Nakata and Langton 2005 Nakata, M. and Langton, M.

“Introduction,”

Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 36.2

(2005): 3–6.

Nathan 2013 Nathan, D. “Progressive archiving: theoretical and practical implications for

documentary linguistics,”

3rd International Conference on Language Documentation and

Conservation (ICLDC), Honolulu (2013, February).

Nathan et al. 2009 Nathan, D., Rayner, S., and

Brown, S. (eds.) William Dawes’ Notebooks on the Aboriginal

language of Sydney : a facsimile version of the notebooks from 1790-1791 on

the Sydney language written by William Dawes and others. London,

SOAS and Blacktown Darug Tribal Aboriginal Corporation (2009).

Olko 2018 Olko, J. “Spaces for participatory research, decolonization and

community empowerment: working with speakers of Nahuatl in Mexico,”

Language Documentation and Description, 16 (2018):

1-34. Online:

http://www.elpublishing.org/itempage/167.

Pratt 2007 Pratt, M.L. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. Routledge

(2007).

Rice 2011 Rice, K. “Documentary

Linguistics and Community Relations,”

Language Documentation and Conservation 5 (2011):

187–207.

Romero Frizzi 2003 Romero Frizzi, M de la A.

Escritura zapoteca: 2,500 años de historia.

INAH, Mexico City (2003).

Smith Stark et al. 2008 Smith Stark, T.C.,

López Cruz, A., Montes de Oca Vega, M., Rodríguez Cano, L., Sellen, A., Torres

Rodríguez, A., Marcial Cerqueda, V., and Rosas Camacho, R. “Tres documentos zapotecos coloniales de San Antonino Ocotlán.” In S.

van Doesburg (ed.), Pictografía y escritura alfabética en

Oaxaca [Pictography and alphabetic writing in Oaxaca], Instituto

Estatal de Educación Pública, Oaxaca (2008), 287–350.

Stoler 2002 Stoler, A.L. “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance,”

Archival Science 2 (2002), 87–109.

Thorpe and Galassi 2014 Thorpe, K., and Galassi,

M. “Rediscovering Indigenous Languages: The Role and Impact

of Libraries and Archives in Cultural Revitalisation,”

Australian Academic and Research Libraries 45

(2014), 81–100.