Abstract

This article explores the impact that a series of Archives Unleashed datathon events

have had on community engagement both within the web archiving field, and more

specifically, on the professional practices of attendees. We present results from

surveyed datathon participants, in addition to related evidence from our events, to

discuss how our participants saw the datathons as dramatically impacting both their

professional practices as well as the broader web archiving community. Drawing on and

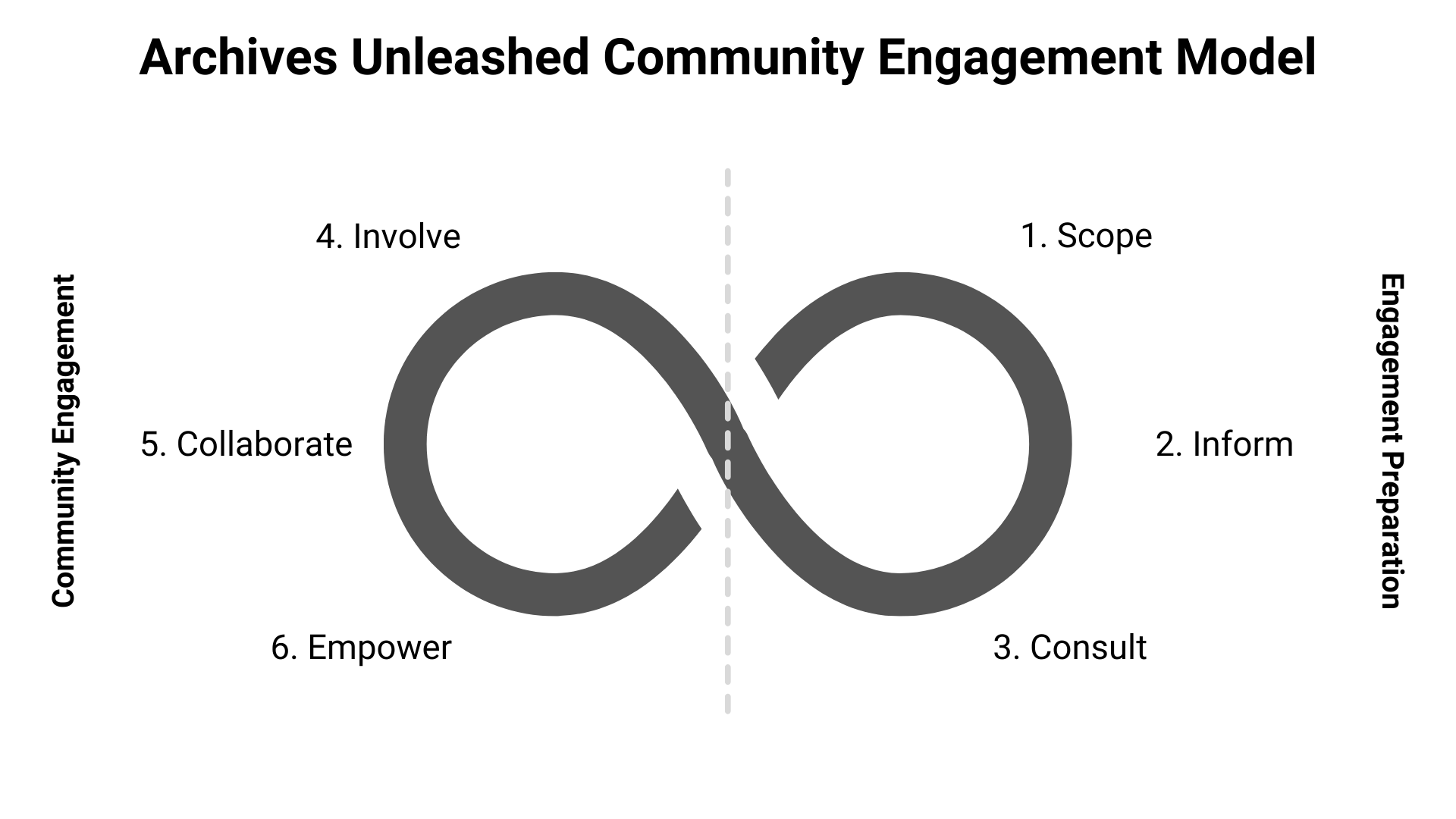

adapting two leading community engagement models, we combine them to introduce a new

understanding of how to build and engage users in an open-source digital humanities

project. Our model illustrates both the activities undertaken by our project as well

as the related impact they have on the field. The model can be broadly applied to

other digital humanities projects seeking to engage their communities.

“If you build it, they will come.” Unfortunately, this does

not apply when developing digital humanities tools and infrastructure. Creating an

open-source tool and fostering a user community around it requires concerted efforts in

the realm of community engagement and outreach. It means building a community, which

involves scoping, involvement, and ongoing engagement. To support our web archive

analysis tools, our project team has run a series of “Archives

Unleashed” datathons, to help engage users not only just with our tools, but

with each other in an attempt to build a sustainable web archiving analysis community.

This article explores the impact that our series of datathon events have had on

community engagement both within the web archiving field, and more specifically, on the

professional practices of attendees. To do so, we draw on and adapt two leading

community engagement models, combining them to introduce our new understanding of how to

build and engage users in an open-source digital humanities project. Our model

illustrates both the activities undertaken by our project, as well as the related impact

they have on the field and can be broadly applied to other digital humanities projects

seeking to engage their communities. Ultimately, the six-stage community engagement

model emphasizes scoping, informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, and

empowering, in an iterative cycle where one can work to continually expand one’s

community.

We wanted to explore the following questions: how has our community been built? What

activities and approaches at these events had the most impact, and which ones could be

improved? What have been the lasting impacts of community engagement? And, finally, what

are the broader and long-term impacts of creating a community within the web archiving

community? These would be critical for both our project but also for others within the

broader digital humanities and library communities interested in similar issues around

community building and engagement.

Our specific focus is on our datathons, which were modeled on the broader

“hackathon” movement. Hackathons emerged in the early 2000s, primarily at first

to rapidly develop new computer software [

Briscoe and Mulligan 2014]. The term itself

combines the terms “hacking” and “marathon,” implying an “intense, uninterrupted period of programming”

[

Komssi et al. 2015]. Over two decades, hackathons have grown to encompass groups

as varied as cultural organizations, government agencies, venture capitalists looking

for new ideas, and other forms of innovation [

Concilio et al. 2017]

[

Pe-Than et al. 2019]. A growing body of literature explores how hackathons have

been adopted within fields as varied as academia, medicine, and civic “hacking.”

Indeed, the model is well-positioned for “enriching social networks,

facilitating collaborative learning, and workforce development”

[

Pe-Than et al. 2019, 15].

While our Archives Unleashed Project drew on the hackathon model, as it allowed for

short focused, yet intensive work periods, we made an early shift to use the term

“datathon” instead. Our first two events (in 2016 and 2017) used the term

“hackathon,” but our project team worried the nature of the term itself would

preclude bringing together a wide array of participants. Our project wanted to engage

with individuals in diverse roles within the web archiving field: not just computer

scientists and developers, but digital humanists, librarians, and curators. The unifying

feature of the events would not be “hacking” on a particular technology, but rather

exploring the implications of new data.

Our article begins with a brief background into the broader Archives Unleashed Project

and the ecosystem that our datathons exist in. We then define the communities we engage

with, both specifically and more broadly. Following this, we introduce the field of

community engagement and note the two main frameworks that we draw from, as well as how

they are combined. Then, through a series of eight interviews with datathon

participants, as well as related evidence from our events, we discuss how our

participants saw the datathons as dramatically impacting both their professional

practices as well as the broader web archiving community. We conclude this article with

lessons learned and how these models can be adapted to work for the digital

humanities.

Background: Web Archives and the Archives Unleashed Project

The world wide web, made public in 1991 by Tim Berners-Lee after being developed as

an internal tool at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), has grown

exponentially over the past three decades. Since its inception, the web has become a

significant site of social, cultural, economic, and political activity. Our lives are

increasingly mediated through technology, a current trend which has grown even

clearer with widespread remote working and social distancing amidst the COVID-19

pandemic. As one of the co-authors of this article has argued, “without using the web, histories of the 1990s will be incomplete for the most

part. Ignoring the web would be like ignoring print culture”

[

Milligan 2019, 20]. Recognizing the significance of the web to

the future historical record, beginning in 1996, the Internet Archive as well as

national libraries in Sweden and Australia, began to carry out the widespread

preservation of web content. This process, web archiving, can be understood as “any form of deliberate and purposive preserving of web

material”

[

Brügger 2010]. Web archiving has increasingly become part of research

agendas for national libraries and archives, as well as memory institutions around

the world.

As of writing, the Internet Archive holds over 900 billion URLs and 60 petabytes of

unique data (a petabyte being 1,000 terabytes). This figure is probably already

dated, as the Internet Archive roughly doubles in size every two years. Despite this

sheer amount of data, or perhaps because of it, access to this data has

lagged. The sheer amount of data, coupled with the lack of research tools, means that

scholars have, in many cases, not been able to carry out fruitful research with this

material. Given the importance of web archives to carrying out histories of the 1990s

and beyond, this is a serious problem. In other words, the data is there – and

considerable expertise has been developed in the collection of web archival data

– but the ability to work with it is not. In addition to the problems of scale, there

are technical challenges of working with Web ARChive (WARC) files, in which much of

this data is saved. We will return to WARC files shortly. Working with web archival

data requires an understanding of both high-performance computing and the command

line. This is, for the most part, out of reach for many scholars. They do not have

the time, the resources, the support, or the training to work with data at scale,

meaning that many research questions from the 1990s onwards cannot benefit from web

data. In other words, this data is increasingly important for research, but it is too

inaccessible for any research at scale.

Our Archives Unleashed Project thus provides scholars and researchers with tools to

explore historical internet content and reduce access barriers to large-scale web

archival data. Established in 2017 with funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation,

the project grows out of a recognition that web archives are critical to

understanding the world around us, and that the scholarly community accordingly needs

approachable and user-friendly tools to access born-digital cultural heritage. The

Archives Unleashed Project exists in several scholarly communities as it is located

at the intersection of researchers, tools developers, and libraries. Our goal is to

improve scholarly access to web archives through a “multi-pronged

strategy involving tool creation, process modeling, and community building - all

proceeding concurrently in mutually-reinforcing efforts”

[

Ruest et al. 2020]. This multi-pronged process manifests itself in three

primary ways. First, the Archives Unleashed Toolkit, an Apache Spark libaray for

working with web archives directly. Secondly, the Archives Unleashed Cloud, a

cloud-hosted infrastructure and web-based front-end to run Toolkit jobs on WARC data

[

Ruest et al. 2021]. Finally, the project co-hosts Archives Unleashed

datathons with local partners. These two-day events bring an interdisciplinary group

of people together to collaborate and gain hands-on experience with web archive data.

At the datathons, users are encouraged to use our project tools – they structure the

sorts of projects that are undertaken. The Archives Unleashed Toolkit and Cloud were

created to provide complementary approaches to working with web archives at scale.

While digital content can exist in a variety of formats, both tools specifically work

with WARC files, as well as their ARC format predecessor. WARC files, an ISO Standard

(28500:2017), are essentially a container-file format that holds collected web

resources together. As the web archiving community has standardized around WARCs,

this has also made the development of a tool and analytics infrastructure possible.

However, as WARC files are inaccessible to the majority of researchers, so much of

the work of the Toolkit and the Cloud revolves around extracting “derivative”

files from web archives: familiar formats such as extracted text files, network

graphs, or statistical information. For example, when exploring the text of a WARC,

several filters can be applied including date, language, keyword, domain, or URL

patterns. This also means that projects can be carried out on a wide variety of

languages; we have seen successful examples of users working with collections in

French and German.

The datathons are the centerpiece of the Archives Unleashed Project’s community

engagement strategy. We want to make sure that the Toolkit and the Cloud both reach

users and are responsive to their needs. As Niels Brügger has argued, there is great

value in “cooperation between web-archiving institutions and

Internet research communities”

[

Brügger 2010]. Our approach to community building has taken several

shapes, from providing robust open-source code documentation, running a Slack group

with open sign-up for sharing and discussion, regularly blogging, providing a

quarterly e-mail newsletter, and – crucially, hosting the datathons discussed here.

We also strive to develop educational resources for attendees, building relationships

with like-minded projects and institutions (from the Internet Archive to university

libraries to national libraries in North America and Europe), and also, participate

in scholarly activities that support and foster information sharing.

Our first datathons predated the Archives Unleashed Project. Between March 2016 and

June 2017, an earlier project team (including two of this paper’s authors) carried

out an initial sequence of four events. These were broader events, primarily focused

on networking and building capacity in the web archiving community (described in

Milligan et al. [2019]), and included 148

attendees from thirteen countries broadly drawing from web archive curators, digital

humanists, and computer scientists.

This paper focuses on the subsequent four datathons as part of our Mellon-funded

project. These events were co-hosted with and held at the University of Toronto

Library (April 2018), Simon Fraser University Library (November 2019), George

Washington University Library (March 2019), and Columbia University Library (hosted

online due to COVID-19, March 2020). Collectively, these four datathons have engaged

with over 70 participants from seven countries and fifty unique institutions.

Participants were predominantly from Canada and the United States, with participants

from five additional countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand,

Egypt, and Hungary. While datathon events were open to a broad spectrum of

information professionals, the majority of participants came from the higher

education sector: university faculty and graduate students, librarians, and

archivists. We had some smaller representation from national archives, non-profit

organizations, museums, and independent researchers. In terms of diversity, we did

not collect information on racial backgrounds, gender identities, or educational

backgrounds; we are accordingly reluctant to make assumptions about our attendees or

interviewees.

These datathons had three primary goals. First, they were designed to introduce

individuals to tools and methodologies of working with web archives at scale.

Secondly, would allow attendees to engage in conversations to facilitate knowledge

sharing and scholarly collaborations. Finally, the events aimed to foster community

around open-source Archives Unleashed tools and web archive practices. While datathon

participants bring a diversity of intellectual and personal perspectives to the

events, in general, they can be categorized as access providers, tool builders, and

data explorers. For the Archives Unleashed Project, focused on fostering an

open-source community, these events would be pivotal for our community engagement

strategy.

Community Engagement

When thinking of community engagement, we were principally informed by the broad

definition advanced by Liz Weaver and colleagues in a paper written for the Canadian

Tamarack Institute, an organization dedicated to engaging with citizens to grapple

pressing community issues. Weaver et al. define community engagement as “people working collaboratively, through inspired action and

learning, to create and realize bold visions for their common future”

[

Waley et al. 2010]. For organizations and institutions, community engagement

is an opportunity to build active relationships with individuals and other entities

for mutually beneficial exchanges. Community engagement is vital as it builds a

relationship that actively seeks to understand the goals, needs, aspirations,

concerns, and values held by a community [

Moore et al. 2016]. Without

engagement and understanding of a community’s composition, there can be

misunderstanding, misrepresentation, miscommunication, and missed opportunities.

Before discussing community engagement models, we need to briefly define what we mean

by community. Community is a surprisingly difficult term to define, as meta-reviews

of scholarly definitions suggest (in addition to those below, see

MacQueen et al. [2001]). We use the definition

suggested by Cobigo et al.: “A community is a group of people

that interact and support each other, and are bounded by shared experiences or

characteristics, a sense of belonging, and often by their physical

proximity”

[

Cobigo et al. 2016, 195]. Indeed, while the web archiving community is

largely virtual, our datathons (apart from our one held online due to COVID-19)

assembled people together in a physical setting to foster community as well.

Accordingly, when we speak of the larger web archiving community, we refer to

individuals, organizations, groups, and institutions that have a shared focus on

experience and engagement with web archiving activities and research.

Within this broad community there is our Archives Unleashed community, composed of

those who who engage with our platforms and support project work. While the web

archiving community is multidisciplinary, it can be a resource-intensive process.

Accordingly, national libraries and post-secondary educational institutions are

overrepresent within the web archiving field (along with the non-profit Internet

Archive), providing significant contributions in the form of education, professional

development opportunities, services, and tools. The professional backgrounds of these

sources are reflected in the demographics and backgrounds of most of our

participants.

Community engagement is critical for many other domains, including business and urban

development [

Fredericks et al. 2016]

[

Mitra 2016], medical [

Joosten et al. 2015], environmental [

Fernandez et al. 2016], open-source and technology development [

Decker et al. 2015]

[

Link and Jeske 2017], education [

Gribb 1992], libraries [

Reid and Howard 2016]

[

Tharani 2019], and social sciences such as archaeology [

Leiuen and Arthure 2016]. Across these studies, however, there are few canonical

community engagement models or frameworks; rather, most of the studies reflect on

specific case studies or activities, and broad understandings of how engaging

communities can benefit a specific group or organization. We did, however, identify

two models that could be adapted as a framework to better understand the goals and

approaches of the Archives Unleashed Project when it came to community building and

engagement. We primarily base our work on the first model, although we draw on

elements of the second as well.

The first model is the Open Community Engagement Process (OCEP) model, developed and

operationalized by the Water Science Software Institute (WSSI). The OCEP model draws

on development methods from Agile Software Development and the Open-Source software

development community [

Ahalt et al. 2013, 42]. This model approaches

community engagement both iteratively and incrementally. Their vision is illustrated

as an infinity symbol, with communities continuing to gain knowledge through all

steps. Crucially, for our own purposes, the WSSI model features “hackathons,”

finding barriers, and disseminating ideas through publications; all of these are

critical aspects of the Archives Unleashed Project, especially the first. The

limitation of the model, however, is its complexity. OCEP includes fifteen stages, is

three dimensional which makes for complicated diagramming, and is difficult to

explain. OCEP is also arguably, for our purposes, too focused on software development

and does not have the wide range of applications that we want to provide.

The second model that we draw on is the International Association for Public

Participation’s (IAP2) “Spectrum of Public Participation.”

IAP2’s model describes five critical stages of community engagement (IAP2 2018). The

first is to inform, or explain an opportunity available to the community. The second

is to consult the community. The third is to involve the community in planning,

implementing decisions, project design processes, and ensure widespread

understanding. The fourth is to collaborate, or to work together to find solutions.

And finally, the spectrum closes with empower, or providing the community with

resources and skills to make their own decisions. While community engagement looks

different in each sector, the processes are broadly applicable and work well for the

Archives Unleashed Project. Understandably, there is no one-size-fits-all-model, as

each sector and discipline have unique sets of needs. While we found the stage model

of IAP2 attractive for being action-oriented, it lacked the stage and flow

organization of OCEP. Accordingly, we combine them as seen in Figure 1.

From the IAP2 model, we drew from the spirit of the five-stages of community

engagement: informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, and empowering. In this,

we are not alone. The IAP2 model has been applied to “project and

program development in fields ranging from health care to environmental planning,

particularly in Australia and Canada”

[

Powell et al. 2010]. As IAP2 focuses on an engagement dynamic originally

rooted in government-civic relations, we have adjusted the categories to fit with

Archives Unleashed Project priorities, our governance structure, and our activities.

For example, our project goals were already defined, so while we do consult with our

community for feedback and input on development processes, many overall decisions are

made by the project team, not by community vote. This would be the case for many

digital humanities projects. It is also important to note, that while we’ve adapted

OCEP’s infinity shape for our community engagement framework, stages do not

necessarily happen independently or one at a time.

We present the six stages of our model below. Note that the datathon process only

appears at stage three of this six-stage process – when we begin to “consult” with

the community – but as the first two stages provide invaluable context, we felt it

was valuable to provide an overview of all of them.

The first stage is to scope. If we look to the aforementioned OCEP model, we can

describe our first stage of community engagement where we scope or identify a problem

or challenge, which becomes “the driving question [which] serves

as an incentive for a specific subset of the community to participate in the OCEP

Open Community Engagement Process] process”

[

Ahalt et al. 2013, 44]. This stage drives purpose and objectives. Once a

problem or challenge has been defined, it is critical to identify the scope of

stakeholders that will collectively make up the community we are engaging. In this

stage, we ask: who is our target audience, what types of individuals, organizations,

or groups are we trying to represent and reach? Who is affected by our “driving

question?” With our Archives Unleashed Project, we leveraged previous work on

the “Warcbase” project (an Archives Unleashed Toolkit predecessor) to identify

needs and barriers of scholars within the digital humanities and social sciences,

when working with web archives [

Lin et al. 2017]. Through this experience and

outreach at diverse conferences and workshops, we gained a sense of who was being

affected by high barriers of access to web archives. Scoping and identifying allowed

our project to focus on three user-types: academics and scholars (specifically within

the humanities, social sciences, and the specific area of the digital humanities);

digital access content providers (primarily librarians and archivists), and tool

builders (with a focus on those in computer science). Note that this scoping provided

the background for the basic structure of our datathons.

The second stage is to inform. The inform stage, as defined by IAP2, is “to provide the public with balanced and objective information to

assist them in understanding the problems, alternatives and/or solutions”

[

IAP2 2018]. Throughout this stage, it was important for the Archives

Unleashed team to share information and summaries around the project goals,

objectives, and road mapping, as well as bring awareness to web archiving access

barriers, and raise an understanding of why our project was important for the

community. One of our initial major activities was to develop a presence on several

information-sharing platforms. This was to both deliver information and grow a

supportive community. Specifically, we used Slack as a way of supportive two-way

communication between the team and the community, as well as encouraging peer-to-peer

discussions and information sharing practices. An accessible signup form allowed for

quick access to our Slack space, and crucially, we could add additional targeted

channels for specific aspects of our project, as well as spaces for general

discussions. We also set up a quarterly newsletter and regularly-published blog

posts.

The third stage is to consult. In our project, this laid the groundwork for the

datathons. As IAP2 identified, the purpose of consulting with a community is to open

dialogue in which individuals can provide “feedback on analysis,

alternatives and/or decisions”

[

IAP2 2018]. This stage identifies the importance of both asking and

listening to voices within the community, and to inform development cycles and

approaches by the Archives Unleashed team. We achieved this in several key respects:

an advisory board, discussions at datathons (as described in this paper), as well as

formally through user surveys and interviews. Indeed, much of the research behind

this paper exemplifies our consultation process.

The fourth stage is to involve, which for us, centered around the datathons

discussed in this paper. This stage speaks to an active mode of participation from

the community. IAP2 defines this stage as a way “to work directly

with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and

aspirations are consistently understood and considered.”

[1] While our project, as an academic one funded by a granting agency, does not

involve community participation at the ultimate decision-making level, involvement

has taken the shape of working collaboratively with our community on tools

development.

Involving our community has been the primary goal of our datathon events, intending

to build a community around the tools that would complement and contribute to the

broader web archiving scholarly community. As attendees participate in our datathons,

they create connections that can support future research collaborations and the

sharing of skills and practices with their broader networks. As the OCEP model

suggests, by participating in events like our datathons, attendees are exposed to

ideas, methods, approaches, skills to address web archiving challenges that may not

have “emerged using traditional disciplinary methods and that

require synthetic knowledge”

[

Ahalt et al. 2013, 45]. In other words, the datathon model we adopted as

a key activity in our involvement stage draws perspectives and approaches from the

community that we otherwise would not have encountered. Notably, involvement overlaps

with the consultation stage.

The fifth and penultimate stage is to collaborate and establish partnerships. Here,

too, the datathons represented a building of both collaborations with our community

and amongst them. The Archives Unleashed Project aims to foster interdisciplinary

collaborations as we sit at the intersection of technology, cultural heritage, and

researchers. Interdisciplinary and multi-institutional collaboration also provides

opportunities for information and resources to be shared more widely. The datathon

structure has provided a glimpse into the ways Archives Unleashed has stepped into a

role of an intermediary for peer-to-peer collaborations and peer-to-institutional

partnerships. As one participant (R4, introduced later in this article) suggested,

Archives Unleashed became a “broker of data,” which for some participants

created a necessary connection between awareness and knowledge by bridging a gap to

accessing web archives data. This has been an active element of our project, and

includes formal partnerships with academic institutions to explore their collections,

co-host datathons together, and crucially build relationships with other projects and

institutions within the field, such as the Internet Archive. Crucially, it has been

critical to identify and develop relationships with projects and organizations that

could help us foster interoperability between projects (such as data transfer APIs or

adapting web-based notebooks).

The final stage, then, is to empower. The IAP2 model defines the empower stage as,

“To place final decision-making in the hands of the

public”

[

IAP2 2018]. However, the Archives Unleashed model approaches

empowerment in a way which encourages and supports the confidence and skills of an

individual to work with web archives, and addresses the objective of lowering

barriers to web archives. Beyond the active participation of empowering our users

through the datathons, we also seek to give resources to the community through

learning guides (text and image-based documents that provide a tutorial-based

approach to working with data), videos, and publications which explain our workflows

and approaches.

Why the infinity symbol? Ultimately, it reflects our approach to long-term

sustainability. After empowering users, we need to consider the scope and think about

what the subsequent projects and iterations will look like, and the opportunities to

further community engagement and enrichment; we then begin to move through the model

again. Cognizant of long-term use of our tools and projects, we are reluctant to post

a firm ending to the model.

This was thus our project’s landscape. We wanted to explore the impact of the

Archives Unleashed datathon events on community engagement through a robust

understanding of these models and the broader scholarly landscape. We return to these

two models later in the paper, as we explore how they meaningfully integrate to help

make sense of the Archives Unleashed Project’s approach to community engagement.

Methods

To understand the impact of our events and inform our proposed community engagement

model, we turned to interviews with participants from our event. To do so, we

compiled a list of all participants who attended our Mellon-funded datathons between

2017 and 2019 (notably our events in Toronto, Vancouver, and Washington DC). Our

primary goal was to craft interview questions and discussions to shed light on steps

3 – 6 (consult, involve, collaborate, and empower). By applying the model to our

datathon, we aimed to validate our proposed model.

Our datathons sought to bring together individuals across three discrete categories,

as identified by our scoping phase. First, attendees from libraries and archives, –

predominantly from post-secondary institutions- or whose professional role was

largely related to curating web archives. Secondly, attendees from the tool-building

community, or those whose professional roles largely related to developing software

for archiving or analysis. And, finally, researchers, or those whose professional

role mostly revolved around using web archives for scholarly research. As our

datathons are roughly structured to include a third of their attendees from each

group, we wanted to interview across these three categories [

Milligan et al. 2019]. Some basic information on the flow of the datathon

can inform the discussion that follows. Our datathons involve teams working in small

groups of between four and six individuals. These groups ideally spanned the three

main participant groups (tools builders/library and archives/researchers) and indeed,

represented diversity within those sub-categories, spanning the range from libraries,

archives, sociology, social media and society scholars, humanists, software

developers, government documents librarians, and so forth.

Datathons provided an open and collegial environment that allowed for the organic

formation of new collaborations and connections. For some attendees, it was a chance

to finally meet people they knew about or follow in the web archiving community but

had never had a chance to meet face-to-face with; while for others, it was an

opportunity to forge an entirely new network. The datathon also afforded participants

the opportunity to meet individuals they would not have met in any other context.

These networking opportunities are especially challenging as there are significant

barriers within the web archiving community, especially as it comprises of so many

institutions, organizations, projects, and individuals from diverse backgrounds. As

the community developed organically over two decades, there is no one overarching

body or group to look to, but rather clusters of groups have formed around specific

organizations (such as meetings at the Society of American Archivists, or digital

humanities conferences, or regional professional groups, or national libraries).

Within the structure of the datathon event, there are various elements and activities

geared towards fostering an open and welcoming community, and helping individuals

develop a sense of belonging. To encourage team formation, we run a sticky note

exercise at the event’s beginning to bring people together into teams. Participants

were encouraged to write down research questions on one coloured sticky note, web

archive collections of interest on another, and finally, tools and infrastructure on

another one. They place their sticky notes on surfaces as organizers physically

cluster the notes to identify emerging themes, and encourage physical groups of

people around those themed clusters. After three or four iterations, teams would be

in place [

Milligan et al. 2019]. This method was adapted from the field of

participatory design [

Walsh et al. 2013].

The sticky note exercise was critical as teams are, of course, the core of the event.

Indeed, the teams that emerged out of this were fundamental in fostering group

dynamics and belonging. As there were no prescribed research problems or questions,

teams were free to decide on the datasets, methods, and research questions –

identified during the sticky note exercise and refined while in their groups. Some

groups did have a technical expert who they could rely on, but many others would need

to work together to approach some of the daunting technical barriers presented by

WARC files and difficult tools. Cognizant of limitations of individual’s personal

laptops or bandwidth constraints at events, we provide cloud-hosted virtual machines

which participants could access remotely.

After working on their projects for two days, the event culminated with final

presentations. Teams would have up to five minutes to present their findings, usually

through a slide show or dynamic demonstration, and then answer one or two questions

from the audience. Judges, selected by the host organization, would then pick one

“winner” who received a token prize of Starbucks gift cards (chosen mainly

because of their cross-border accessibility).

For this paper, a total of eight semi-structured interviews were conducted via

Skype, and subsequently transcribed for reviewing and coding to identify emerging

themes and relationships. All interviewees consented to have the interview recorded

and agreed to be identified in any ensuing publications with a description of their

professional role. While all interviewees had attended at least one of the three

Mellon-funded datathons, four of them had also attended pre-Archives Unleashed

Project datathon. We will introduce each interview subject again below in prose as

they appear in results, but for convenience we use abbreviations for subsequent

mentions. They are listed in Table 1.

| Code |

Description |

Category |

| R1 |

Librarian, large national library |

Library/Archives |

| R2 |

Librarian Developer, large U.S. private university |

Tools Developer |

| R3 |

Faculty Researcher, large U.S. public university |

Researcher |

| R4 |

Graduate student and developer, large U.S. public university |

Tools Developer |

| R5 |

Librarian, mid-sized Canadian university |

Library/Archives |

| R6 |

Archivist, large U.S. private university |

Library/Archives |

| R7 |

Graduate student and developer, mid-sized U.S. public university |

Tools Developer |

| R8 |

Graduate student researcher, large U.S. private university |

Researcher |

The interview questions revolved around three general areas. First, we were

interested in interviewees’ professional background and experience, as well as their

scholarly interests. We wanted to understand their knowledge and experience with web

archiving prior to attending the datathon. Secondly, we explored their datathon

experience, focusing on their overall experience and impressions from the event,

their familiarity with similar events, and crucially whether their scholarly

community or practice has changed as a result of the datathon. Finally, we concluded

with general questions around their thoughts on the future of web archiving,

including challenges, opportunities, and gaps that they deemed relevant to the future

of the community. These questions were developed as a means to understand the degree

to which Archives Unleashed had successfully created a scholarly community, how the

datathons impacted community formation, and what, if any, were the impacts on the

broader web archiving community.

Results

The following section is divided into our main themes: backgrounds and pre-existing

knowledge of web archiving, the impact of the datathon experience (notably

skill-building, exposure to diverse practices, community formation, and inculcation

of a sense of belonging), the datathon within the web archiving community context,

and finally, general reflections on the future of web archiving and barriers in the

field. As noted, these all primarily shed light on steps 4 – 6 (involve, collaborate,

and empower) of the community model. For convenience, an overview of findings is

provided in Table 2.

| Theme |

Summary of Findings |

| Knowledge of Web Archiving and Backgrounds |

- Knowledge of archiving was primarily based on and accumulated through

professional experience and employment, not formal training.

- Datathon increased knowledge of web archiving on both a high level

(theoretical aims, goals, systems) and a granular level (technical

skills).

|

| Impact of the Datathon on Professional Practice |

Datathon contributed to skill-building

- All agreed their technical knowledge and skills increased as a result

of their participation.

- It was a unique opportunity to work directly with web archival data

and specific analysis tools.

- Final projects allowed participants to share information, approaches,

and methods for working with web archival data.

- Helped participants make a stronger case for web archiving within

their institutions and communities.

|

|

Exposed attendees to diverse interdisciplinary

perspectives

- Small group collaboration allowed participants the opportunity to work

with a diverse range of perspectives.

- Participants had to adapt and communicate across disciplinary

lines.

|

|

Fostered community formation

- Created a space in which individuals would not have otherwise

met.

- Participants are equipped with skills to be ambassadors within the

broader web archiving community.

- The datathon also influenced a shift for participants who attended

multiple Archives Unleashed datathons, as they organically grew into a

mentorship’s role both at the event and within the larger

community.

|

|

Fostered a sense of belonging

- Event activities and elements were designed to foster an open and

welcoming atmosphere.

- The sticky note exercise, adapted from participatory design, helped

individuals find colleagues and topics they most identify with.

- Working together in organically formed groups, individuals felt like

their frustrations, limitations, and struggles with technical barriers

could be empathised by others due to this shared experience.

|

| Areas for Improvement |

- Two-day time limit and diminished energy on projects after the

physical meeting is a constraint of the datathon model.

- Limited discussions on broader issues relating to policy, ethics, or

theory.

- Technical expertise within each group varied.

|

| The Road Ahead |

- Overall optimism for future directions of web archiving: increased

access to web archives and promise of scholarship.

- Consensus about the value and significance that web archives bring to

a wide range of disciplines.

- Time lag between archival dataset creation and their use.

|

Table 2.

Summary of interview results

Knowledge of Web Archiving and Backgrounds

The first step in understanding a community has to be understanding its composition.

Where do members come from? What technical or social knowledge of web archives did

they have? Accordingly, we asked participants about their varied professional

backgrounds and scholarly interests. As attendees at a datathon, the participants

interviewed all in some way worked with web archives in their current or most recent

position: whether they were conducting crawls for institutional collections,

providing access to researchers, or creating tools to interact with web archival

data. While working in the field, however, when asked about the ways in which they

had become familiar with web archiving, many pointed to an accumulation of knowledge

based on practice through work experience. Knowledge, in a sense, was a result of

trial-and-error and through professional positions, rather than through formal higher

education training. This was seen across the board from those with degrees in the

LIS, humanities, engineering, and computer science disciplines. Indeed, experience

was often obtained outside of the field but applied to it. For example, one librarian

working at a large national library (R1) had previously worked with special media

formats at scale, an experience which lent itself well to web archiving. Another

librarian working at a large research library (R2) had been working with social media

data. With both examples, we see a pattern where previous experience with diverse

digital formats carried over to their work in web archiving.

All eight participants agreed that the Archives Unleashed datathon had increased

their knowledge of web archiving (generally related to higher-level thinking –

theoretical aims, goals, processes) outside of any technical skills they learned. One

respondent, a researcher at a large U.S. public university (R3), noted that the

datathon provided foundational knowledge of some of the working parts and concepts

within web archiving, for instance, WARC files, derivatives, as well as the

possibilities of web archiving analysis. R2 emphasized that the datathon validated

for them the connection between web archiving and scholarly research. For R2, as well

as two additional interviewees – one a graduate student and digital humanities

developer (R4) and another a digital scholarship librarian at a Canadian university

(R5) – the event brought an understanding of how researchers may want to use and look

at web archive data. This was important for both tool developers as well as

librarians to help inform their ways to support users and colleagues. Finally,

another participant – an archivist at a large U.S. private university (R6) – remarked

that the event had helped them to think about “what we might change on our end as the

staff members creating these collections, to allow for this other kind of research

that we hadn't really supported before at our institution.”

Impact of the Datathon on Professional Practice

With backgrounds established, we wanted to explore the degree to which our events –

as an exercise in community engagement – had meaningful impacts on professional

practices. We can cluster their responses into four main themes. First, the datathons

contribution to skill-building. Secondly, how the event exposed attendees to diverse,

interdisciplinary perspectives. Thirdly, how the events fostered community formation;

and fourthly – and finally – how our events fostered for some a sense of belonging.

We explore each of these in turn.

Despite the varying levels of experience that participants brought to the datathon,

all agreed there were several important lessons and skills they took away from their

datathon experience. This meant building or adding to their technical repertoires,

even amongst those with technical expertise coming in. For those who work with web

archive collections as part of their professional practice, such as R3 and R4, their

primary focus during their everyday work is to collect information. This means that

they rarely have opportunities to, really dig in and work with the data up close.

Indeed, this ability to work with the data itself is where the datathon model shined

for participants. By digging into the mechanics of data and the intricacies of tools

in a small, supportive environment, group collaborations led to discussions around

the challenges, limitations, and other structural practices of web archiving.

Notably, the wrap-up activity – where the groups presented their final projects – was

noted by participants as an opportunity to showcase final projects and to share

information.

A number of specific tools were learned, as well. All respondents mentioned the

Archives Unleashed Toolkit. Social media analysis tools such as twarc (

https://github.com/DocNow/twarc),

APIs, and approaches to visualization were also common answers. Notably, R4 noted the

importance of learning Spark: “prior to the second workshop, I

really had never used Spark before. I kind of knew what it was but just had never

spent the time to learn how to use it,” and argued that future work and

collaborations would not have emerged if they had not attended the datathon and

learned how to use Spark. The overall impact of the event on lowering barriers was

also noted by R8, a graduate student at a large private U.S. university, who

expressed ongoing efforts to “help archivists to feel more

confident or less afraid of the technology of command line and things like that so

that they could use Archives Unleashed and the tools that you're developing. Don't

be afraid of it. This is great. That's the great thing about the datathon,

right?”

Another crucial dimension of the datathon was helping participants make a stronger

case for why professions needed to adopt these methods and approaches to web

archiving. In other words, it allowed them to better advocate for the value of web

archiving within their institutions and communities. As R1, the librarian from a

national library described, institutions and organizations are “not as likely to put money towards it or they’re not as likely to just believe in

it” without tangible outputs or use cases like one might see coming out of

a datathon. This was echoed by R6, an archivist at a large U.S. private university,

who indicated that it is hard to advocate for web archiving “when

administrators often want statistics and usage numbers and quantitative reasons to

support the work, we can’t necessarily say that people are using web archive

yet.” As R5, the librarian at a mid-sized Canadian university considered,

institutions may not also “realize the commitment that’s needed

to do this well.” Through tangible examples, R5 expressed that though their

mandate as a digital scholarship librarian, “I find that

explaining to them why this is important, how they can use this technology, all of

a sudden it becomes less of an abstract fear and more of an oh, I see why this is

important and why I want to learn it.” By being able to showcase actual

projects from the datathons, participants were able in turn to bring lessons and

approaches back to their institutions.

Exposure to Diverse Perspectives

Similarly, participants regularly commented on the benefit of working in small groups

(discussed in the previous section) with a diverse range of perspectives unified only

in some cases by a shared interest in web archiving. Given the event, this was

sufficiently cohesive. Indeed, as R7 (a graduate student and developer at a mid-sized

U.S. public university) noted, it represented an “opportunity to

network with like-minded people.” The range of perspectives and background

groups was in and of itself a real boon. R7 spoke at this at length, highlighting

that:

You don’t realize how much you don’t understand until you

try to explain something that you think is obvious. So that’s something I think

really came out when I was working with teams, was trying to convey things that

seemed obvious to me, or intuitive to me, but then other folks were rightly

questioning “why would you do it that way?” and I would say, “well how else

would you do that?” Basically, going back and forth was really

educational.

This back-and-forth would be represented in the final projects as well, as R7

stressed how this creativity was borne out in the final presentations. For example, a

researcher with a flair for visualization could make a concept come alive. R7

reflects, in these final presentations, participants could “transform[ing] topics that you never really thought you could take a look at and

making them into visual representations.” Similarly, connections between

different disciplines could pay off in the long term. R8, a graduate student, was

able to connect with an archivist as part of their datathon team, leading to critical

insights around data brokering, collections strategies, and beyond; as she expressed,

“a lot of things sort of came together just through that one

interaction with her. And that led to a lot of insights for me,” noting

that they corresponded after the event as well.

Community Formation

While us organizers had the initial goal of building community around the specific

Archives Unleashed Tools (i.e., community with our project),

coincidently, we were able to encourage connections within the

community that did not involve our tools. Indeed, part of this was simply breaking

down disciplinary barriers. One of our attendees, R6, an archivist at a large private

university, saw the event as helping to “break down the

librarian, archivist versus scholar researcher dichotomy ... all of [these] people

are in the same room equally as peers.”

Indeed, through the interviews, we saw community formation taking shape as

participants emerged as ambassadors within the web archiving community, their home

institutions, and professional communities. For example, R3 – a faculty researcher at

a large U.S. university – drew a direct relationship between the datathon and their

current scholarly practices. For them, the skills and connections learned at the

event allowed them to expose colleagues to web archiving practices and demonstrate

the possibilities that WARC files provided. Another, R2, the librarian developer at a

private U.S. university, noted that it informed their own development work on a

related project that used WARCs and some of the web archiving APIs. When it came time

to work on this project, the datathon “gave us confidence that

when we were trying to do the same thing, that it was the right way to

go.”

Within the series of events that were run, participants who attended multiple events

matured in their participation as they could mentor new attendees. R7 noted that the

first time they attended the event, they were “still learning

what a WARC was,” and R3 reflected that “the projects

that [they] worked on became increasingly more technical over multiple

datathons.” Crucially, these repeat attendees shifted organically into a

mentorship role, having the confidence to help other group members based on the

technical skills and expertise developed iteratively over datathons.

Sense of Belonging

In general terms, the world of web archiving is unfamiliar and unintuitive to

researchers, librarians, archivists, and even some tool builders. At the same time,

those who work in the field are quickly confronted with an overwhelming and

intimidating amount of data in a relatively idiosyncratic file format (in that WARCs

are seldom encountered outside of the web archiving field). To lower these barriers,

we want to inculcate a sense of belonging.

A sense of belonging has been defined in a critical article by Hagerty et al. as

“the experiences of personal involvement in a system or

environment so that persons feel themselves to be an integral part of that system

or environment”

[

Haggerty et al. 1992]. Peer support and a sense of belonging have been

identified as two critical factors for overall mental health as well amongst

students, and are essential goals of our events as well (drawing on our experience as

educators as well) [

McBeath et al. 2018]. A sense of belonging is critical to

whether an individual participates in a broader community.

The importance of the sticky note exercise in creating a sense of belonging came

across in the interviews. As R7 explained, “we did the exercise

on the board with the Post-Its and things like that, and I think that really

helped me find a group and also find something of interest.”

This was also nurtured through sustained group work. As R3 noted, there was a

recognition that the “majority of people were in the same boat

because working with web archives is difficult.” By being able to work

together, the events for many “normalize[d] the experience with

the tools and the technology and limitations” as R3 explained. R4, a

graduate student and developer at a large U.S. university, saw the event as akin to a

“travelling web archive or reading room,” and by making

data accessible to teams (many of whom who could now talk to the curating librarian

responsible for the data) we were akin to a “broker of data.” Indeed, these

partnerships were mutually beneficial as participants were able to access web archive

data, at the same time, attention was brought to unique institutional datasets that

exist, but may not be widely known about.

Areas for Improvement

While participants were positive around the overall impact – conveyed through

post-event surveys and interviews– ideas did arise around how this event model could

either be better refined or perhaps would not fit all of our community-building

goals. Some of these, notably the diverse range of technical expertise or

disciplines, as well as the slowed momentum of collaboration after the event [

Komssi et al. 2015], were expected. Other suggestions led us to engage more

deeply with pedagogical literature.

The focus on “data,” implicit in the name “datathon” itself, had some

downsides. It led to an emphasis on technical issues and working with discrete

datasets themselves, which had the effect of preventing discussion on broader issues

to do with policy, ethics, or theory. R3 gave an important example of “issues of representation and what this means and what these gaps

mean that aren't data specific” as something that did not feel welcome at

the event as a topic of discussion. One could look at a dataset, but this left out

questions that might (as R3 again noted) allow us to “look at the

whole [web archiving] life cycle.”

With such technical questions and the overall ethos, issues were also raised around

the diversity of technical expertise. As teams largely formed themselves through the

collaborative team building exercise, some teams ended up without much in the way of

technical strength. R6, an archivist at a large U.S. private university, found

themselves in such a group and wished that there had been more of an expectation for

peers (even if they were in another group) to help “peers who are

struggling to get them more towards a middle ground rather than identifying the

people who are doing a really stellar job and pushing them farther ahead from the

folks who are struggling.” We were inspired by this, and in future

grant-funded work, are pursuing a formal mentorship program to help pair expertise

with researchers in a more targeted and inclusive way.

Finally, the loss of momentum after the event was a shortcoming identified by

interviewees and our project team alike. The short two-day nature of the event means

that it largely relies heavily on exploratory projects that may not have a readily

apparent route forward to a larger study or publication. It also reflects the

difficult nature of the tools, and how outside of the resources provided by the

datathon, they may continue to be too difficult. However, we need to consider that

engagement is not just a short-term milestone, nor is it just using a particular

toolkit or approach. Rather, it is again community. Several

participants noted that while they do not use the tools, they do have them tucked

away as a resource to recommend when a patron or a colleague might want to work with

web archival data.

The Road Ahead

Participants were all asked about their thoughts on the future of web archiving.

While broad in nature, this question was met with optimism from respondents who were

generally excited about the direction of web archiving and the opportunities for

scholars, access providers, and tool builders (and everyone in between). On the

collection side, R2 (librarian developer at a large national library) saw a shift

from national to institutional collecting, which would notably involve “large growth in subject-based collecting that is likely to be of

more value for both the historical record and for scholarly work.” As well,

there was a consensus that web archive collections hold immense value for current and

future researchers, and web archives have – as R3 explained – “a

potential to add a lot more rigor and also allow us to share data and in lots of

other spaces.” We also saw that most participants were happy about the

Archives Unleashed Project; R7, for example, noted that they felt “feel very good about the tools that you’ve been developing, like

those are exactly the right sorts of tools and tearing down the right sorts of

technical barriers that are going to make the adoption happen faster.”

Yet there was also a sense that the process of web archiving analysis might be ahead

of where researchers are right now; that we are, perhaps, along with the web

archiving field more generally, laying the groundwork for future work. As R2 notes,

while there is undoubtedly “long-term massive significance to

[this] scholarly activity ... [it will] happen in a timeframe that will be

frustrating long ... [but the pace of adoption] should not at all be taken as a

reflection on the significance of the work.” R1, a librarian at a national

library, remarked that Archives Unleashed “opens the door to

(those computational) conversations because it starts to break down [barriers to]

the technical part.” Indeed, use of archival collections often lags behind

their creation; as R6 argued, “in archives we take a pretty long

view of time and history, and just because (few) are using it now doesn’t mean

that people aren’t going to want it (web archive data).”

Conclusions: An Emerging Community Model

| Stage |

Archives Unleashed Activities |

| Engagement Preparation |

|

Stage 1: Scope

- Identify the problem or question.

- Identify stakeholders that comprise the community.

|

- Leveraging experience from our previous Warcbase project.

- Identifying needs and barriers of digital humanities scholars.

- Categorize stakeholder groups: researchers; digital access content

providers; tool builders.

|

|

Stage 2: Inform

- Provide information so that the community can understand present

problems and potential solutions

|

- Share information and summaries around our project objectives, and

proposed pathway.

- Establish information sharing platforms with regular

engagement.

- Offer opportunities for contributions.

- Provide regularly monitored lines of communication.

|

|

Stage 3: Consult

- Conduct an open dialogue with the purpose of gathering feedback from

the community.

|

- This stage involves the project leadership asking questions and

actively listening.

- Assembling and consulting with an Advisory Board.

- Conducting surveys and interviews.

|

| Community Outreach |

|

Stage 4: Involve

- Work with the community to ensure community concerns and wishes are

considered.

|

- For the Archives Unleashed Project, we interpreted this stage as a way

of working collaboratively with the community on tool development.

- A primary undertaking has been directly involving community members in

our Archives Unleashed datathons.

- Sharing skills and practices with the community, growing out of

datathon experiences.

|

|

Stage 5: Collaborate

- Collaborate and establish partnerships.

- Foster interdisciplinary collaborations, both peer-to-peer and

peer-to-institution.

|

- Partnerships with academic institutions for the purpose of resource

sharing and exposure, specifically web archive collections.

- Datathons offered a significant connection between institutions who

created web archive collections and researchers who wanted to use

them.

- Broader collaboration and partnerships fostered interoperability with

other web archiving projects and tools.

|

|

Stage 6: Empower

- Encourage and support scholars in building confidence and skills

needed to work with web archives.

|

- Datathons empowered individuals through learning opportunities.

- Project invested in developing accessible learning-based resources,

for instance learning guides, video tutorials, and documentation.

- Resources aimed at empowering users to feel comfortable and confident

when exploring web archives

|

Table 3.

Summary of the Archives Unleashed Community Model approach

Through this, an emerging community model takes shape for both the Archives Unleashed

Project as well as our role within the broader ecosystem; this has implications for

other digital humanities projects. It is summarized in Table 3. Archives Unleashed is

located within the web archiving ecosystem, with important links to the digital

humanities, historical, computational social sciences, and computer science fields.

From these interviews and our own experiences, we understand that “if you build it, they will come” mentality does not work, and

active engagement to build relationships and communities is essential. The goal

through datathons was to build a community around our tools that would complement and

contribute to the other connections taking shape.

From our earlier discussion, we identified two community engagement frameworks – the

Water Science Software Institute’s Open Community Engagement Process (OCEP) and the

International Association for Public Participation’s (IAP2) “Spectrum of Public Participation,” and brought them together in our

Archives Unleashed community model. We can see that our combination of the OCEP and

IAP2 models works reasonably well, capturing the breadth of activities taking place

through our datathons. IAP2 captures the main categories, more or less; and OCEP

captures the need to see the cycle as an infinite loop, where we continually navigate

and improve as we move through the community engagement model.

Overall, the Archives Unleashed Project has successfully built a community around the

scholarly practice of exploring web archives and created unique opportunities for

individuals with a wide variance in backgrounds, skills, and experience to connect

and collaborate. All participants identified at least one, and in many cases several,

tangible skills that they learned. They also spoke to the important aspect of having

the opportunity to forge new collaborations, which have positively impacted their

professional practices and research collaborations. It also bears out the hackathon

literature, which suggests the ability for these events to “enable building a community of users and strategic networks,”

[

Komssi et al. 2015, 64] seen in our discussions around community

formation, a sense of belonging, and skills acquired by participants through the

Archives Unleashed datathons.

Without community engagement, projects would live and work in silos. The models we

engage with here, as well as the modified version that we advance, are all part of

the broader ways in which our projects and others in the digital humanities create a

space for and recognize collaborative and interdisciplinary work.

Works Cited

Ahalt et al. 2013 Ahalt, S., Minsker, B., Tiemann, M.,

Band, L., Palmer, M., Idaszak, R., Lenhardt, C., and Whitton, M. “Water Science Software Institute: An Open Source Engagement Process,”

5th International Workshop on Software Engineering for

Computational Science and Engineering (SE-CSE), San Francisco, California,

May 2013.

Brügger 2010 Brügger, N. “Web

Archiving: Between Past, Present, and Future.” In R. Burnett, M. Consalvo,

and C. Ess, (eds), The Handbook of Internet Studies.

Wiley-Blackwell, Malden (2010), pp. 24–42.

Cobigo et al. 2016 Cobigo, V., Martin, L., and

Mcheimech, R. “Understanding Community,”

Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 5(4) (December

2016): 181-203.

Concilio et al. 2017 Concilio, G., Molinari, F. and

Morelli, N. “Empowering Citizens with Open Data by Urban

Hackathons,” Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government (CeDEM),

Austria 2017.

Decker et al. 2015 Decker, A., Eiselt, K. and Voll, K.

“Understanding and Improving the Culture of Hackathons: Think

Global Hack Local,”

IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). El Paso,

Texas, 2015.

Fernandez et al. 2016 Fernandez, M., Piccolo, L.,

Maynard, D., Wippo, M., Meili, C., and Alani, H. “Talking Climate

Change via Social Media: Communication, Engagement and Behavior,”

Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science,

Association for Computing Machinery (WebSci ’16), Hannover, Germany, May

2016.

Fredericks et al. 2016 Fredericks, J., Caldwell,

G. A. and Tomitsch, M. “Middle-Out Design: Collaborative

Community Engagement in Urban HCI,”

Proceedings of the 28th Australian Conference on Computer-Human

Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery (OzCHI ’16), Tasmania,

Australia 2016.

Gribb 1992 Gribb, W. J. “Field

Experience through Community Engagement: A Model and Case Study,”

The Professional Geographer, 70(2) (2018):

298–304.

Haggerty et al. 1992 Hagerty, B., Lynch-Sauer, J.,

Patusky, K., Bouwsema, M., and Collier, P. “Sense of Belonging: A

Vital Mental Health Concept,”

Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6(3) (1992): 172–177.

Joosten et al. 2015 Joosten, Y., Israel, T.,

Williams, N., Boone, L., Schlundt, D., Mouton, C., Dittus, R., Bernard, G., and

Wilkins, C. “Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach

to Obtaining Meaningful Input from Stakeholders to Inform Research,”

Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American

Medical Colleges, 90(12) (2015): 1646–1650.

Komssi et al. 2015 Komssi, M., Pichlis, D.,

Raatikainen, M., Kindström, K., and Järvinen, J. “What are

Hackathons for?”

IEEE Software, 32(5) (2015): 60–67.

Leiuen and Arthure 2016 Leiuen, C. D. and Arthure, S.

“Collaboration on Whose Terms? Using the IAP2 Community

Engagement Model for Archaeology in Kapunda, South Australia,”

Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 3(2)

(2016): 81–98.

Lin et al. 2017 Lin, J., Milligan, I., Wiebe, J., and

Zhou, A. “Warcbase: Scalable Analytics Infrastructure for

Exploring Web Archives,”

ACM Journal of Computing and Cultural Heritage, 10(4)

(2017): 22:1-22:30.

Link and Jeske 2017 Link, G. J. P. and Jeske, D. “Understanding Organization and Open Source Community Relations

through the Attraction-Selection-Attrition Model,”

Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Open

Collaboration, Association for Computing Machinery (OpenSym ’17), Galway,

Ireland 2017.

MacQueen et al., 2001 MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E.,

Metzger, D. S., Kegeles, S., Strauss, R. P., Scotti, R., Blanchard, L., and Trotter

II, R. T. “What is Community? An Evidence-Based Definition for

Participatory Public Health,”

American Journal of Public Health, 91(12) (2001):

1929-1938.

McBeath et al. 2018 McBeath, M., Drysdale, M. T. and

Bohn, N. “Work-Integrated Learning and the Importance of Peer

Support and Sense of Belonging,”

Education & Training, 60(1) (2018): 39–53.

Milligan 2019 Milligan, I. History in the Age of Abundance? How the Web is Transforming Historical

Research. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Kingston and Montreal

(2019).

Milligan et al. 2019 Milligan, I., Casemajor,

N., Fritz, S., Lin, J., Ruest, N., Weber, M., and Worby, N. “Building Community and Tools for Analyzing Web Archives through

Datathons,”

Proceedings of the 18th Joint Conference on Digital

Libraries, Champaign, Illinois, June 2019.

Mitra 2016 Mitra, N. “Community

Engagement Models in Real Estate — A Case Study of Tata Housing Development

Company Limited,”

Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 5(1) (2016): 111–138.

Moore et al. 2016 Moore, T., McDonald, M.,

McHugh-Dillo, H., and West, S. “Community Engagement: A Key

Strategy for Improving Outcomes for Australian Families,”

Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne,

Victoria. Available at:

https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/226801100 (Accessed: 21 May 2020).

Pe-Than et al. 2019 Pe-Than, E. P. P., Nolte, A.,

Filippova, A., Bird, C., Scallen, S., and Herbsleb, J. “Designing

Corporate Hackathons with a Purpose: The Future of Software Development,”

IEEE Software, 36(1) (2019): 15–22.

Powell et al. 2010 Powell, D., Gilliss, C., Hewitt,

H., and Flint, E. “Application of a Partnership Model for

Transformative and Sustainable International Development,”

Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 27(1) (2010):

54–70.

Reid and Howard 2016 Reid, H. and Howard, V. “Connecting with Community: The Importance of Community Engagement in

Rural Public Library Systems,”

Public Library Quarterly, 35(3) (2016): 188–202.

Ruest et al. 2020 Ruest, N., Lin, J., Milligan, I., and

Fritz, S. “The Archives Unleashed Project: Technology, Process,

and Community to Improve Scholarly Access to Web Archives,”

Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Digital Libraries,

Proceedings of the 19th Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, Wuhan,

China, August 2020.

Ruest et al. 2021 Ruest, N., Fritz, S., Deschamps, R.,

Lin., J., and Milligan, I. “From Archive to Analysis: Accessing

Web Archives at Scale Through a Cloud-Based Interface,”

International Journal of Digital Humanities (2021).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42803-020-00029-6.

Tharani 2019 Tharani, K. “Shifting Established Mindsets and Praxis in Libraries: Five Insights for Making

Non-Western Knowledge Digitally Accessible through Community Engagement,”

Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 4 (2019):

1–13.

Walsh et al. 2013 Walsh, G., Foss, E., Yip, J., and

Druin, A. “FACIT PD: A Framework for Analysis and Creation of

Intergenerational Techniques for Participatory Design,”

Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery (CHI ’13), Paris,

France.