2010

Volume 4 Number 2

Abstract

This extended interview between founding H-Urban editor Wendy Plotkin and H-Urban

reviews editor Sharon Irish traces the early history of online scholarly

communication via H-Net, H-Urban, and COMM-ORG, informed by Plotkin’s background as a

planner and community activist in the 1970s and 1980s. After work with community

development corporations on the East Coast, Plotkin entered graduate school in urban

history at the University of Illinois at Chicago. During this period in the early

nineties, Plotkin had a job with the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), and then

collaborated on the development of the forum that became H-Net. In addition to

standards and protocols about new communication technologies, face-to-face

relationships grew out of online exchanges, often with lively disagreements about the

direction of H-Net. Plotkin’s own broadening use of digital tools prompts her

concluding reflections on historians’ continuing need to use the Internet to overcome

physical and intellectual fragmentation, and how the Internet has democratized the

field of history.

Preamble

For three years now (2007-10), I have been the project coordinator for the

Community Informatics Initiative of the

Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of

Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). Community informatics (CI) is an emerging

field, with continuing debates about definitions and core questions. Informatics is

the study of information systems and processes, including computational, social, and

individual cognition. CI, with its social emphasis, aims to understand not only how

communities access, create, organize, and share information, but also the types and

qualities of connections between and among communities. CI scholars and practitioners

examine the uses of information and communication technologies in

geographically-distinct and underserved areas, and work with local communities to

achieve their goals. This focus stresses that reciprocity must characterize

relationships that involve the distribution and use of information. Community members

spearhead both naming the issues of the community and the process leading to

solutions.

As an historian, I puzzle over which concepts contributed to the emergence of

community informatics. One convergence of ideas I wanted to investigate occurred in

the 1990s. Seventeen years ago, in 1993, Wendy Plotkin was a graduate student in

urban history at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Her graduate

assistantship gave her an early entrée to the world of computers and the Internet.

She used this experience to become a key participant in the launching of

H-Net (Humanities and Social Sciences on

Line), an organization devoted to using the Internet for scholarly communication,

together with a professor of political history, Richard Jensen, and another graduate

student, Kelly Richter, who specialized in Civil War history. The first of the

scholarly forums was

H-Urban, which

Wendy established as a model for the later forums, and which is how I came to know

her.

Wendy and I met in person for the first time in Chicago, Illinois, in July 2008,

after having developed a virtual relationship since 2002, when I became review editor

for H-Urban. I wanted to document her memories and ideas relating to the early years

of H-Urban. During two conversations in Chicago — one at a noisy restaurant in

Greektown and a second follow-up meeting in the Italian neighborhood near the campus

of the University of Illinois at Chicago — Wendy shared her insights about online

scholarly communication. Our conversations then continued in email exchanges between

Wendy and me that covered the history of H-Net and H-Urban, her growing interest in

geospatial technologies, and her ideas for future projects. This article thus takes

the form of an extended interview in three parts. The first focuses on Wendy’s

background as a planner and community activist in Boston in the 1970s and 1980s. The

second examines her decision to become a historian upon her return to Chicago (her

hometown) in 1990, and her involvement in the creation of H-Net, H-Urban, and

COMM-ORG, in the subsequent decade. The third considers her broadening use of digital

tools, reflections on historians’ continuing need to use the Internet to overcome

physical and intellectual fragmentation, and ideas about how the Internet has

democratized the field of history.

— Sharon Irish

Participating in the Community Revolution of the 1970s

| Sharon Irish | Wendy, your background in urban planning and policy (especially your years of

employment in Boston on housing and economic development issues) really influenced

your historical scholarship. Would you talk a bit about this period of your life,

and the relationships between planning and your work in urban history? |

| Wendy Plotkin | After graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign with an

undergraduate degree in history (1971), I headed to Boston. I worked in several

jobs at the regional planning agency, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), first in housing and then in

transportation.[1] In the mid-eighties, I got a

master’s degree from Tufts University in urban and environmental policy (1983-87),

writing a thesis on the Boston Housing Partnership, a major community development

project.[2]

|

| | After getting my master’s, I worked for the state of Massachusetts (1985-87)

during the administration of Governor Michael Dukakis. Amy Anthony, the director

of the Executive Office of Communities and Development (EOCD), found innovative

ways to help the community development corporations (CDCs) that were becoming

prominent players in the creation of Massachusetts housing and business by that

time. Then, as now, it was difficult for CDCs to secure operating funds; most of

the available funding was for specific projects, putting the proverbial cart

before the horse. The CDCs with which we worked didn’t have the money to function

and train people in development before becoming involved in complex projects. EOCD

provided CEED (Community Economic Enterprise Development) funds that enabled them

to do just that, and I worked on “Special Projects.”

[3]

|

| | From 1987-89, I worked for the city of Boston, helping CDCs get financing for

housing and commercial projects. I was the liaison between the banks and the CDCs

in securing loans that were packaged with federal and state subsidy and tax credit

programs. By that time, I had also became personally involved with the Fenway CDC, which functioned in the

neighborhood in which I lived. The Fenway CDC was a nationally known organization

that had its roots in fighting arson-for-profit. In the 1980s, it organized

against gentrification, developing affordable and ecologically sound housing that

included long-term subsidies to maintain a racially and economically diverse

neighborhood. I saw up close, not only the economic, but also the social benefits

accruing to community members who participated in decisions that affected their

lives. They helped to influence the course of development in their neighborhoods,

and experienced strong communal ties that grew as a result of their

collaboration. |

| Irish | This aspect of your work intersects with community informatics because it values

participatory decision-making, using a variety of tools to build strong

relationships and coalitions. |

| Plotkin | Yes. And I was particularly impressed by what might be considered an early form of

low tech “community informatics,” in the work of Urban Planning Aid. Urban

Planning Aid was a consulting firm established by MIT and Harvard students in

Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1966 to “provide

technical and informational assistance and promote transfer of skills to low

income community and workplace groups in Eastern Massachusetts around issues of

housing, industrial health and safety, media access, and backup

research.” [Urban Planning Aid 1972] I became aware of them through their publication Less Rent: More Control: A Tenant’s Guide to Rent Control in

Massachusetts when I became involved in an action contesting a rent

increase in my Beacon Hill building in 1974.[4]

|

| Irish | Beacon Hill…pretty impressive! |

| Plotkin | Not really - I lived on the less famous side of Beacon Hill, which had a legacy

steeped in sailors, prostitutes, and Jewish immigrants. Its housing stock

consisted of old three- and four-story apartment buildings, not the Georgian-style

mansions on the other side. Massachusetts’ 1972 rent control law required

landlords to maintain their properties, and my neighbors and I documented the

deficiencies in the building and asked the owners to deal with these prior to

being considered for a rent increase. |

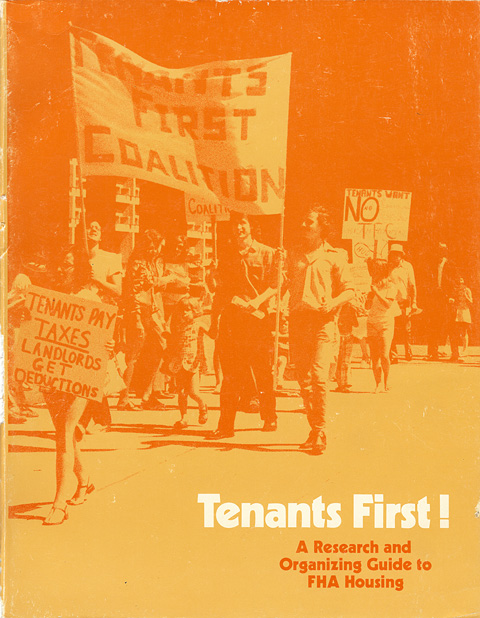

| | Over the years, Urban Planning Aid produced a series of similar manuals, such as

Tenants First: A Research and Organizing Guide to FHA

Housing and How to Use OSHA (the landmark Occupational Health and

Safety Act of 1973). They also warned of the perils that existed in reliance on

community development corporations because of their roles as developers and

owners, which would blunt their potential as activists on behalf of

tenants.[5]

|

| Irish | And yet…you became involved in the Fenway CDC. |

| Plotkin | I think that this is because, at heart, I am a moderate, and I wasn’t ready to

rule out the benefits to be gained by CDCs, as more radical activists were. While

I understood the arguments made by those critical of CDCs, I thought that they

represented the possibility of a more socially-conscious, benign type of

development, especially if there were external mechanisms — such as the existence

of tenant advocacy groups — that would co-exist with them to temper any turn to

parochialism and profit orientations. What attracted me to either type of

organization — CDC or advocacy group — was their potential for involving

“ordinary citizens” in the decisions that affected their daily lives, the

goal that Saul Alinsky so well expressed. |

| | Because of my more moderate approach to “community organizing,” it is not

surprising that I became an academic and an educator, rather than an activist. I

was more interested in investigating society’s dynamics than in siding

unequivocally with one side or the other. Furthermore, as an academic, I created

H-Urban and Comm-Org to encourage academics and professionals to share scholarship

with each other, rather than to disseminate it to “ordinary citizens.”

|

| | These choices suggest the increasing distance that grew between my past and career

as an academic. However, my years in Boston impressed on me the value of

collaboration, something that was given short shrift in the academic discipline

that I chose, history. As a graduate student at Tufts, as a participant in

neighborhood organizations, and as a professional providing resources to

community-based organizations, I was engaged in enterprises that involved — and

were strengthened by — collaboration. When I returned to Chicago in 1989, it was

this appreciation for partnership that would be the most important influence on

how I applied the digital revolution to the field of history. |

History, the Digital Revolution, H-Net, and H-Urban/Comm-Org

| Irish | 1989 was, thus, a major turning point in your life. After working in Boston for

seventeen years, you decided to return to Chicago, your hometown, and re-enter

academia for a Ph.D. in urban and American history. Why did you decide to leave

planning and become a historian? |

| Plotkin | In fact, when I returned to Chicago, I considered entering a Ph.D. program in

either planning or history. I did not feel that I had adequate

training to address the complex issues that planners dealt with, and, if I were to

continue as a planner, I wished to have more time to explore the theoretical

issues (e.g., the “greater good,” competing visions of the “ideal”

physical environment) and to strengthen my planning skills. This is where chance

played a role. I interviewed with both the history and planning departments at the

University of Illinois at Chicago; the historian with whom I met was far more

interested in my joining the program than the planner. Furthermore, I had never

lost my appreciation for history in Boston, and I always saw history as another

route to the goal of understanding how cities operated. |

| Irish | You worked with Perry Duis and Richard Fried at the University of Illinois in

Chicago, finishing your doctorate in 1999. Your dissertation was on the dynamics

of urban neighborhoods in Chicago, with a special focus on racial deed

restrictions and restrictive covenants. These are legal documents that limit

access to housing on the basis of racial categories and/or religious affiliation,

is that right? |

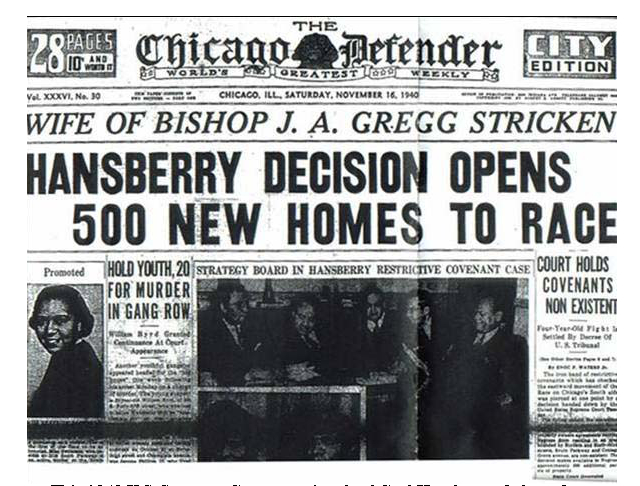

| Plotkin | Yes. My interest in racial deed restrictions was stimulated by my community

experiences in Boston. CDCs were part of a major movement in the 1960s and 1970s

that endorsed the concept of neighborhood-based control, itself an outgrowth of

the emphasis on “participatory democracy.” As a person who had witnessed

(during my childhood) the use of such control to thwart racial integration in

Chicago — one of the most segregated cities in the nation — I wanted to explore

this “negative” type of community organizing, so as to raise consciousness

about the darker side of neighborhood-based control, and alert newer organizations

to the dangers of parochialism. I was especially interested in the use of racial

deed restrictions by developers and neighborhood groups, because, contrary to

public understanding, these were an example of de jure discrimination in the

North. My current book, Deeds of Mistrust: Race, Housing and

Restrictive Covenants in Chicago, 1900-1953, is nearly finished, and I

have a website entitled “Racial and Religious Restrictive Covenants in the United

States and Canada” on the topic. A follow-up project, entitled Deeds of

Whiteness, will be a national study of these restrictions.[6]

|

| Irish | Let’s turn now to your involvement with computers in the early 1990s. |

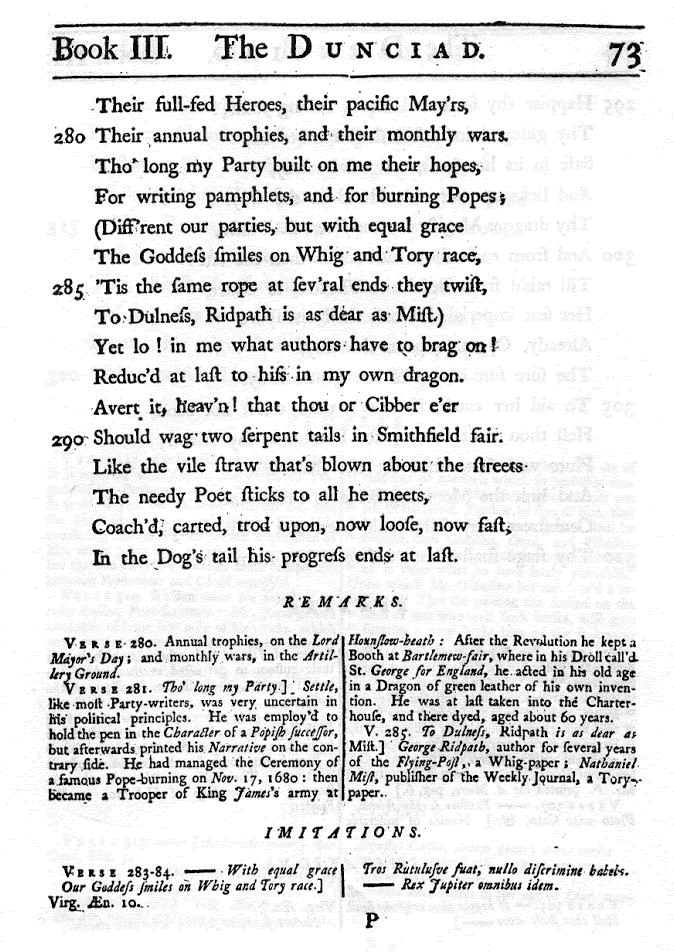

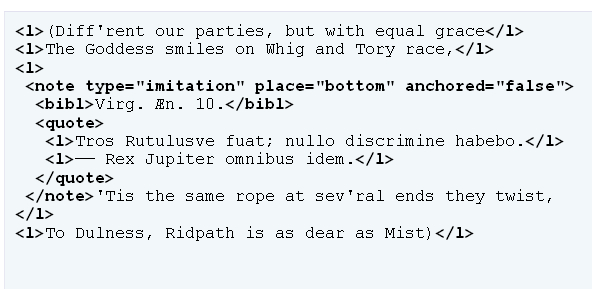

| Plotkin | While I was a graduate student at UIC, I had a job working with the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI).

The TEI is an international collaboration (then funded by the National Endowment

for the Humanities and its European counterparts) to pave the way for digital

versions of literary and linguistic texts, including historical ones.[7]

|

| | Working at the TEI triggered my interest in the effects of digitization on the

production of history. In 1991, I decided to do an independent study on the

subject, and chose faculty member Richard Jensen to guide me. Richard was already

legendary for his intellectual contributions to political history (contributing to

the “ethnocultural” and “quantitative history” schools with his landmark

The Winning of the Midwest

[8]). However, it was his activities in

training historians in the use of computers for quantitative methods that led me

to him. From 1971 to 1982, he served as the founding director of the Newberry

Library’s Quantitative Institute, which trained over 800 scholars in using

quantitative methods in history. Certain similarities existed between Jensen’s

goals for the institute and H-Net. Both brought together scholars with similar

interests in an emerging field of history, and tended to attract participants from

smaller universities and colleges who had fewer networking opportunities than

those with larger faculties and student bodies [Jensen 1983]. |

| | At the time I approached Richard, I think he was already expanding his interest

to include the qualitative uses of computers in history, especially in scholarly

communication.[9] Working with him, in 1991-92, I researched and wrote a

paper entitled “The Use of Electronic Texts in the Historical

Profession,” interviewing historians, librarians, publishers,

archivists, and documentary editors.[10]

|

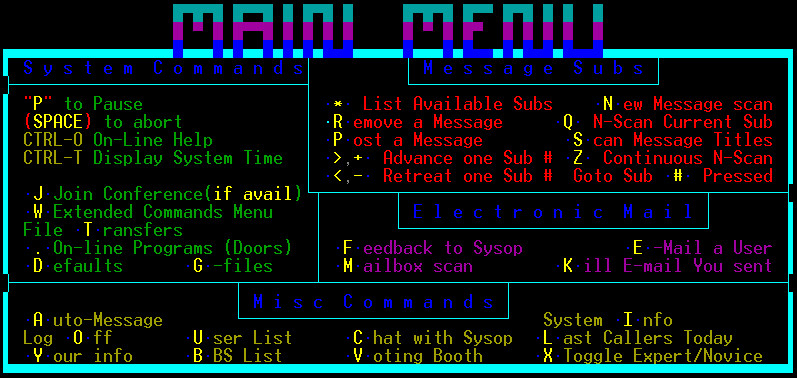

| | Towards the end of my work on the paper, Richard invited me to meet with him and

Kelly Richter, another graduate student in history. The two of them had begun

discussing creating an online scholarly history forum, using the “bulletin

board” technology that was one of the early popular means of connecting

individual computers. However, I recommended that this new forum instead use

Listserv, a more advanced technology I had familiarity with through my work at the

TEI. Listserv was superior to the “bulletin board” technology in a number of

ways: it had the advantage of automatically creating “logs” of all messages,

as well as having the capability of storing files. Thus, in creating H-Net,

Richard, Kelly, and I decided to use Listserv as the communications software. |

| Irish | What was H-Net like in its infancy? |

| Plotkin | It was exhilarating, one of the most exciting times in my life. The three of us

took a memorable road trip to Washington, D.C. and the National Endowment for the

Humanities (NEH) in October, 1992 (and also celebrated Richard's birthday). We

stopped in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on a crisp, cold, fall day, and Kelly saw the

name of an ancestor on one of the gravestones. In Washington, we visited both the

American Historical Association (AHA) and the NEH, and shared our ideas with them.

Both organizations were encouraging. We went back to UIC and prepared an

application for funding by NEH. The first grant was turned down, but the second

one, submitted after H-Net had begun operations, succeeded. Thus, H-Net began with

funding only from UIC and the volunteer services of people such as Kelly and me,

although Jim Mott, a former student of Jensen who was a programmer in statistical

analysis (SPSS), soon added his expertise. |

| Irish | What was your role in creating and shaping H-Net? |

| Plotkin | I had proposed to Richard that I create the first H-Net list, on urban history. He

agreed, and we discussed a name. I suggested Urban-H, and he said that H-Urban

would be better — all of the subsequent lists would begin with H-. I agreed, and began planning H-Urban. |

| | In 1993, what came to be called the Internet was already in operation, although

in its more primitive stages, and there were a few history forums on it. However,

these were a mix of serious and amateur historians, and the quality was mediocre,

for the most part (the classical scholars were far ahead).[11] Thus, when we created H-Net and H-Urban, we consciously set out to develop

something that would be different — that would be dominated by scholars and

practitioners in auxiliary disciplines, and that would have a scholarly tone.

Unlike the more free-wheeling online groups on history at the time, H-Net

incorporated a strong commitment to core values in academia, including deference

to more established scholars and high standards for the content of scholarly

communication. Our goal was to wed the best contemporary practices in humanities

scholarship to the new possibilities opened up by the Internet. To do this, we

created “moderated” lists, in which all messages would have to go through an

advanced graduate student, faculty member, or practitioner. Early on, possibly

after the lists had started, we also decided that each list should have a

“board” of the leading scholars in the field. Thus, drawing on the

democratic nature of the early Internet, I began to write to urban historians of

some repute, and asked them to serve on H-Urban's board. Most agreed. We created

the idea of separate lists for the board, and Edboard-Urban was born. |

| | On February 24, 1993, I sent out the first H-Urban (and H-Net) message; many more

followed. The messages were a mix of announcements, queries, and attempts to

promote discussion — the latter the least successful, unless we were discussing

urban poetry or urban films. In those early days, as a graduate student, I took

the time to abstract book reviews in the major journals, and also to develop

mini-essays on a variety of urban historical topics. When key urban historians

passed away, I'd summarize the major obituaries or write one myself. I began to

combine conversations on the same topic, and to store them on the Listserv

“fileserv” (or server), alerting our subscribers that they could obtain

this summary with an e-mail with a command such as “Get Electric Streetcars.”

Membership grew from 25 to 50 to over 100. (We are now over 2,000.) |

| Irish | What about the other early H-Net groups? |

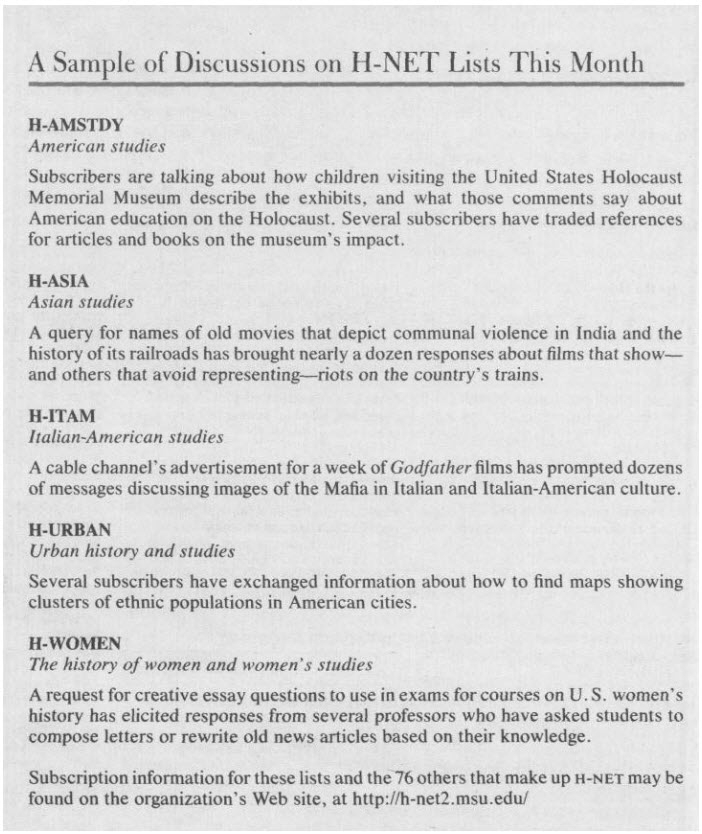

| Plotkin | H-Urban was not alone for long. H-Women followed soon, as did H-Ethnic, H-Film,

H-Family, H-Teach, H-Labor, H-Law, H-Medieval, H-Politics, H-CivWar, H-South,

H-SHGAPE, HOLOCAUS and H-Antisemitism, HAPSBURG, H-Albion, H-Asia, H-Africa,

H-Business, H-Diplo, H-Film, H-German, H-Grad, H-Ideas, H-Judaic, H-Latam,

H-Local, H-Oz, H-PCAACA, H-State, H-West (I am probably forgetting a few). A few

of these lists pre-dated H-Net, and eventually became H-Net lists in the first

years of the organization, incorporating H-Net’s more scholarly approach and

features when they did. |

| | Beyond this list of names, I think it is useful to emphasize the extent to which

H-Net became a “virtual community,” one that, for many of us, was more

meaningful than the cohort groups at our places of work. At the time, graduate

students and faculty members who were interested in the use of the Internet were

in the minority, and H-Net brought us together in a medium that allowed ongoing,

easy contact. |

| | Furthermore, in spite of the assertion that involvement in the Internet led to

social isolation, important personal and professional relationships formed among

us. At least in my own case, the chance to meet these colleagues face to face

enhanced, although it did not replace, these relationships. |

| Irish | Did you stay involved in H-Net after you started H-Urban? |

| Plotkin | Yes, the other lists initially used H-Urban as a model, and I began to teach the

other moderators how to use Listserv. We created H-Staff and H-Editor, and used

these in-house lists to discuss how to run these new types of forums. Each list

had to create standards for subscription and postings, with the goal of nurturing

“virtual communities” of scholars and students in similar fields. There

were questions about the extent to which this new tool should be used to

democratize scholarly communication; for example, should H-Net conform to

traditional scholarly and copyright standards? Some argued that the Internet

should be used to do away with many of the hierarchical and proprietary practices

within academia; others thought that these should be maintained at the same time

that a more informal means of communication was offered. |

| Irish | Where did you stand? |

| Plotkin | I am a traditionalist, and thus I supported the second of the above views. For

example, I argued that all postings should include a signature and an

institutional affiliation, and, ideally, the academic status of the author. My

argument for doing this was not to defend special privileges for those higher up

on the ladder, but to provide H-Urban and H-Net readers with the background

necessary to appraise the contributions of those who posted, and to promote the

networking goals of the lists. |

| Irish | Would you say that you represented the mainstream or the minority in your

views? |

| Plotkin | Probably the mainstream, at the time. I had significant differences over copyright

with Richard Jensen, which led to tension between us. Richard argued for a more

liberal approach in borrowing material for use on the Internet; I disagreed.

Meanwhile, those who posted to the lists began to test other boundaries early on —

from sending e-mail with no capitalization to offering political tracts on current

or historical topics.[12] While

this occurred on all lists, lists such as H-Antisemitism and HOLOCAUS had special

difficulties, with Holocaust deniers insisting on their rights to post. The

editors of these lists stood firm in refusing to entertain discussions of marginal

or questionable scholarship, and, in so doing, did H-Net a service in establishing

a reputation for scholarliness. |

| Irish | What were some of the highlights of these early years? |

| Plotkin | For me, the most important was when H-Urban became the first list to invite a

moderator from outside of the United States (Alan Mayne, then at University of

Melbourne, now at University of South Australia). This, and the international

membership, added a “multicultural” element to H-Net. Less traveled scholars

such as I learned about the reverse of seasons in the northern and southern

hemispheres, the different “summer” vacations of scholars in different parts

of the world, and the range of academic titles and ranks in different

countries.[13] The expansion of the list staffs

also created a community of editors within each list, among whom policies and

practices were discussed and refined. Soon after Alan joined me, others followed:

Martha Bianco (a graduate student and then instructor at Portland State

University), Mark Peel (a historian at Monash University, Australia), Maureen

Flanagan (a historian at at Michigan State University), and Keith Tankard (then a

historian at Rhodes University in South Africa). Our first non-historian was

Mickey Lauria, a leading planning scholar, who is among the longest serving

editors. |

| | To accommodate decision-making among us, we created the first “editors list”

(Edit-Urban) for discussion of policy. Soon, we established the “editors'

manual,” which was a list of our policies. This grew over time as more

decisions were made, and became a resource for training new editors. We debated

such things as enforcing proper grammar (after someone sent in a posting in the

e.e. cummings mode of all lower case), and agreed that we would require proper

grammar and would retain the right to edit postings. We began to check and expand

citations of scholarship that were sent in, and, as history resources became more

numerous on the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1993 and 1994, we added links to

information about scholarship. We also reserved the right to reject

“non-scholarly” postings. |

| Plotkin | H-Urban posted the first book review on H-Net (long before we had a formal review

system), and also introduced the idea of a subscriber's survey. |

| Irish | With all of this time given to H-Urban, did you start to shift your focus away

from H-Net as a whole? |

| Plotkin | Yes, for a variety of reasons. I needed to focus on my dissertation and other

graduate studies, so as to develop the traditional historical skills and knowledge

that would give me credibility within the historical community. Thus, I only had

so much time to give to H-Net and H-Urban, and H-Urban increasingly took much of

my time. The policy disagreements that I had had with Richard Jensen about H-Net

made me more inclined to devote time to H-Urban. Not only that, but I was not

primarily interested in the administrative, technical, or even policy aspects of

H-Net and H-Urban — I was in it primarily for the scholarly benefits it had to

offer. |

| | Finally, H-Net stayed at UIC for only two years, and moved in 1995 to Michigan

State University. Thus, graduate students and faculty at Michigan State University

began to take more of the leadership and staffing roles. |

| Irish | Why did H-Net move to Michigan State University? |

| Plotkin | Michigan State (MSU) was more willing than UIC to invest in H-Net, and H-Net’s

rising star, Mark Kornbluh, was a faculty member in the History Department. |

| Irish | How did the change in location affect H-Net? |

| Plotkin | Well, first, Michigan State made a major financial commitment to H-Net, and this

investment allowed H-Net to take advantage of the powerful technology of the WWW,

and to provide a permanent technical and training staff. This was a scenario that

fulfilled the commitment of Mark Kornbluh, and another H-Net activist, Peter

Knupfer, to move H-Net beyond just e-mail lists. |

| Irish | Was there anyone who disagreed with this scenario? |

| Plotkin | Yes, in fact — Richard Jensen and Jim Mott — and this turned out to be the crux of

the 1997 H-Net election. I should give you a bit of background on this. |

| | In 1994, H-Net had organized itself and elected Richard Jensen as Executive

Director for a three year term. At the same time, Mark Kornbluh was elected as the

chair of the H-Net Executive Board. In 1997, H-Net had its first contested

election for executive and associate directors: Richard Jensen and Jim Mott

against Mark Kornbluh and Peter Knupfer. |

| | Each of the slates had a different vision for H-Net. Richard Jensen argued for a

reliance on the discussion lists as the core of H-Net, while Mark Kornbluh

advocated for the development of WWW pages to augment the discussions. In the end,

the H-Net editors elected Mark Kornbluh and Peter Knupfer as Executive and

Associate Director, and H-Net developed according to their vision ([Marcus 1996], [Guernsey 1997]). |

| Irish | Which vision did you support? |

| Plotkin | The Kornbluh-Knupfer one. It was my interest in digitization of texts that had led

to my involvement in H-Net, and I was fascinated by the possibilities of making

primary and secondary documents available on the WWW, as well as teaching and

other materials. On H-Urban, we created an annotated list of WWW sites related to

urban history. We increased our production of book reviews, and created a Teaching

Center, with scores of syllabi.[14]

|

| Irish | Did these features add to H-Urban’s success? |

| Plotkin | Definitely, largely because we were able to attract dedicated and committed

scholars such as Clay McShane, Roger Biles, and you to take on the book review and

other features![15]

|

| Irish | Did you have a web designer, as well, or did H-Net do the web design? |

| Plotkin | We were extremely fortunate to have Charlotte Agustin, a historian with an M.A. in

history, working as a web designer for us. Charlotte was an outstanding designer,

who developed and maintained the all of the H-Urban webpages. However, Charlotte’s

contribution went well beyond that. She has a fine analytical mind, and

participated in the intellectual decisions that went into the Teaching and

Weblinks pages, eventually, in effect, taking over all aspects of the teaching

site, including editing and posting the syllabi, among our most popular products.

Charlotte and I shared a belief in the significance of producing syllabi that had

a consistent format and complete citation information on the readings, which added

to the time needed to process them. However, I believe that it is this effort that

made our syllabus collection stand out from others on the web, although Charlotte

had to step back from her intense activity with H-Urban to return to

income-producing activities. |

| Irish | You worked very hard, as I recall, trying to generate discussion on H-Urban. You

contacted leading scholars in the field, asking them to contribute substantial

commentary on significant urban history questions so that you could post these

online and moderate a discussion. It wasn’t a resounding success, was it? Why

not? |

| Plotkin | Because those of us who created H-Net had not really taken into account the

significant obstacles that stood in the way of online discussion among historians

in college and university settings, especially in the United States. Most

important was an academic reward system that favored formal, print, peer-reviewed

communication (as opposed to ongoing, informal, online communication). Such a

system produced so much pressure on academics to publish and teach that there was

little time left for informally broadening their horizons in an international and

interdisciplinary forum. |

| | I had hoped to encourage a flowing discussion of major arguments and assertions

within urban history. However, most historians preferred to use their research and

writing time to put these ideas on paper for publications that would garner them

credit rather than on a public Internet list. Note that it is not the online

environment that was necessarily the most important aspect here, but the emphasis

within academia of formal, peer-reviewed communication manifested in books,

articles, and reviews. |

| Irish | Were there any other factors that discouraged discussion? |

| Plotkin | One that relates to urban history, I believe. Urban history has increasingly

fragmented into distinct geographical, chronological, and thematic domains.

National boundaries still act as barriers to comparative work, and, in the United

States, most historians of 18th, 19th, and 20th century cities show little

interest in seeking continuities with the earlier cities in the rest of the world.

This is partly because they believe that the “modern” city was a significant

departure, if not a complete break, from earlier cities, but also because the

continents seem so different. |

| | Similar barriers exist between political, social, cultural and other historians of

cities, who have not succeeded, I believe, in establishing connections between

their findings. |

| | These differences limit the ability of many urban historians to develop and

discuss their topics in a comparative framework, the type of focus to which the

Internet is especially suited. I have often thought that groups with a more narrow

focus — e.g., H-UrbTransport, H-UrbHousing, H-UrbReligion — would be more dynamic

than H-Urban, because, at this level, historians begin to share more

interests. |

| Irish | Was your decision to create COMM-ORG in 1995 an effort to move in this direction? |

| Plotkin | In part, although I was also interested in testing a different model from H-Urban.

I established COMM-ORG — an on-line seminar on the history of community organizing

and community-based development — in November 1995, and served as editor through

December 1996. Funded by the University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities program,

COMM-ORG was an online forum involving periodic presentations of working papers

and discussion on the history and practice of community organizing and/or

community-based development. It allowed me to examine the possibility of online

scholarly collaboration in the specific area of urban history that was closest to

my personal and professional experiences in Boston and the dissertation research

that evolved from that. |

| Irish | Why did you use this more formal approach? |

| Plotkin | Because of my frustration at the refusal of scholars to engage in substantive

discussions on H-Urban. I thought that, if papers were presented, this might

trigger discussion – and, even if it didn’t, there would at least be the outcome

of an online piece of scholarship. |

| Irish | Was this more successful? |

| Plotkin | Not really. Again, it was difficult to get leaders in the field to contribute

papers, for an obvious reason — COMM-ORG did not include peer-review prior to

publishing papers. Thus, there was no academic credit for preparing a paper to

post on COMM-ORG. We were lucky to get as many good papers as we did, from senior,

Internet-adept scholars who no longer had to worry about tenure and promotion;

junior scholars who appreciated the opportunity to post work that had been

rejected for formal publication; and academics in disciplines where publishing was

less important. |

| Irish | What happened to COMM-ORG? |

| Plotkin | Under the current able editorship of Randy Stoecker, who produced one of the best

papers during my period overseeing it, COMM-ORG continues to be a vital forum for

practitioners and scholars. For the most part, it focuses on current practices and

theory of community organizing, rather than its history.[16]

|

| Irish | Wendy, we have been looking backwards at events that occurred over ten years ago.

Since then, you have matured as a scholar and taught at a major university. How

has the passage of time affected your perspective on H-Urban? For instance, what

is the impact of newer technologies on H-Net and H-Urban? |

| | In June, the Chronicle of Higher Education published

an article entitled “Change or Die: Scholarly E-Mail Lists,

Once Vibrant, Fight for Relevance.” It quoted T. Mills Kelly, the

associate director of the Center for History and New Media at George Mason

University, and a former H-Net editor, as saying that the advent of blogging,

Twitter, and similar technologies is likely to make “e-mail lists…increasingly

irrelevant”

[Young 2009]. Do you agree with this assessment? |

| Plotkin | No, not at all. Mills was basing this assessment on his experience with those

lists in which he was involved. According to the Chronicle, Kelly noted that “one of

those lists shut down for lack of use in 2005, and the activity on the others

sputters along with little useful information.”

|

| | However, H-Urban’s experience has been virtually the opposite. Our subscriptions

are coming in at a faster pace than at any other time except in the initial years,

with a total of almost 2000 active subscribers from 48 countries. The United

States accounts for a high proportion of these — approximately three-quarters —

with Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, France, and the Netherlands

next in order. Most of those joining seem to be younger faculty and graduate

students, with an increasing number coming from outside of the United States,

although H-Urban subscribers include many — although not all — of the leading

international urban historians. A cross-section of subscribers within the last

year includes an assistant professor of history at St. Olaf’s College in

Minnesota; a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Chicago; and an

assistant dean of a Maryland pharmacy college who works on environmental health

and historical epidemiology. |

| Irish | To what do you attribute this growth? |

| Plotkin | Largely, to the greater comfort of a new generation with the Internet, and the

availability of improved facilities for accessing it. However, two other factors

play a role, I believe: H-Urban’s reputation for quality, including posting

information that is considered to be relevant, and our outreach to new board

members from outside of the United States. |

| | However, H-Urban occasionally loses subscribers, which is always disappointing to

me — and it seems to be some of the older, more established scholars who choose

not to stay. I don’t think that this is a result of the medium, but because they

have less need for the announcements, calls for papers, book reviews, and syllabi

that comprise the major features of H-Urban. It’s not that this material is not of

a high quality, but that scholars can obtain this material from journals. |

| Irish | Do you still believe that there is a role for online discussion in the scholarly

world, or have you accepted the more traditional preference among historians to

record their findings primarily in books and articles? |

| Plotkin | I do believe that there is a role for online work, and I have not

accepted the traditional preference for books and articles at the cost of online

discussion. In fact, these years of teaching and research have led me to question

the scholarly forms and practices that evolved during the era of print. If one

examines these forms and practices closely, one sees that, to a great extent, they

arose because of the reliance on print. For example, the high cost of producing

and distributing scholarship made it more efficient (in terms of cost and time) to

package and deliver lengthy manuscripts and unrelated collections of articles and

book reviews at periodic intervals. |

| Irish | Haven’t historians continued to use these forms for intellectual reasons? |

| Plotkin | Yes and no. I think that, within history, the book form has persisted because

history has been considered a humanities discipline, and the art and craft of

writing is deemed a key part of historical production. Writing ability carries

greater weight among historians than among social scientists — a standard with

which I agree. |

| | In addition, this attitude has been buttressed by the growing belief in the late

20th century in the organic and subjective nature of

history. By “organic,” I mean the sense that most arguments are so complex

that they require a book-length document for their exposition — and that a

historian must display the skill to grapple with intertwining layers of evidence

and analysis over a specified chronological period to be able to reveal the past

in all its complexity. |

| | By “subjective,” I refer to the effects of the skepticism and linguistic

concerns that seeped into all academic disciplines in the 1960s and after. Within

history, these factors heightened the sense that authors’ worldviews

and assumptions were the engines that organized the strands of

evidence and analysis into unique configurations — and that historian’s books

were, in fact, an intricate mix of fact and interpretation that was as much art as

science. |

| | However, I believe that this outlook denies the degree to which good historical

monographs consist of debatable facts and ideas that can

be separated and evaluated individually and sequentially in online forums as well

as in the “manuscript” package. I am not saying that books should be

abolished, but that historians should begin to develop intermediate evaluative

processes in which the ideas and evidence within them are tested, before they are

packaged as articles and monographs. |

| | As for journals, the choice of publishing a group of articles and book reviews in

periodic issues is also a reflection of the economies of print. Except for the

occasional special issue, these typically combine articles on topics that have few

common themes or connections. Online journals have generally continued this

packaging of dissimilar materials. With the digital medium, I believe it makes

more sense to publish the articles singly, so that it is easier for the scholars

to save and organize them. |

| | There is also a need for a classification system that would tag all

books and articles, regardless of location or chronological period, in a

consistent manner. The classification systems currently in place do not cross

national boundaries, and were not created by urban scholars. Even in the digital

age, it is difficult for a researcher to find all of the relevant work on a topic

– and this process takes up a significant amount of time. If urbanists in a

variety of disciplines collaborated to create and maintain a classification system

that would encompass existing and new work, this would speed up that part of the

research process that involves identifying and retrieving relevant work on a given

topic across geographical and chronological lines. |

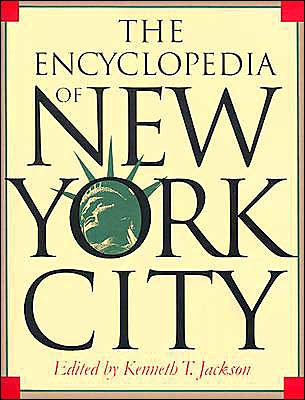

| Irish | Are your beliefs in this area tied to the latest of the projects in which you are

interested — the Historical Encyclopedia of

Urbanism? |

| Plotkin | Yes. The Encyclopedia — a collaborative, online,

historical encyclopedia of international urban studies and history — would provide

a central place for storing up-to-date knowledge on key concepts in urbanism, in a

manner that would promote comparative analysis. The idea for this emerged from my

experiences in teaching historical methods to undergraduates. I had always

encouraged students to use encyclopedias as a means of obtaining a concise summary

of the state of knowledge on a topic at the start of their research. However, when

I assigned the entry on “the city” in the Britannica

Online, I (and the students) were shocked at the Western bias in the

entry, with almost nothing on the cities of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This

led me to investigate the history of encyclopedias, including Encyclopedia Britannica, and to evaluate the importance of

encyclopedias, which many scholars dismiss as serious sources for scholarly

information. |

| | This dismissal is ironic, because, in recent years, encyclopedias on all topics

have proliferated, leading to what I have labeled “intellectual sprawl.” The

idea of an encyclopedia is to publish concise information about a topic so as to

provide a source for scholars who do not have the time to keep up with the

thousands of books and articles published each year. I consider this not only a

sound rationale for their creation, but one that is increasing in importance each

day, as the volume of information on any topic multiplies geometrically. |

| | However, the proliferation of encyclopedias defeats their ability to serve their

audiences, for it forces the reader to keep track of each new encyclopedia on the

topic of her interest. Print encyclopedias are expensive, and most individuals can

afford only one or two. And, in these days of the Internet, how likely is it that

either faculty or students will make a special trip to the library to consult an

encyclopedia? |

| Irish | How does the Historical Encyclopedia of Urbanism aim

to stop this proliferation? |

| Plotkin | By borrowing some of the lessons learned from Wikipedia. Wikipedia, in spite of

its commonly cited flaws, has shown how a single encyclopedia can become a

“standard” if it is easily accessible, current, and of an acceptable

quality. Accessibility comes from being online and freely available. Currency of

information is obtained through the involvement of groups of individuals in

updating it on an ongoing basis, rather than relying on a small number of

contributors chosen by an editor to update it once every five or six years, if

ever. Quality is secured by having the encyclopedia editors provide ongoing

oversight of information for terms of two to four years instead of taking on the

massive job of updating all knowledge in a field in one or two years. |

| Plotkin | Quality is certainly among the most important issues, and products such as

Wikipedia are always suspect on this score. However, I would argue that the

traditional model of creating encyclopedias also diminishes quality. The Encyclopedia aims to remedy the defects in both the

Wikipedia and traditional models. |

| Irish | You certainly don’t shy away from ambitious goals! How will this project promote

quality scholarship? |

| Plotkin | In the first place, the Encyclopedia would be

maintained by editors who are established scholars in the field. One of their

roles would be to ensure that all information in the encyclopedia is accurate, and

that the entry on any given topic is written in a coherent manner. |

| | In the second place, the Encyclopedia would not

rely on a single scholar to summarize the state-of-the-art knowledge on a given

topic, as do traditional encyclopedias. Rather, it invites scholars from across

the globe to incrementally suggest additions, subject to approval and editing by

the original author of the entry or one of the editors. I believe that this will

result in a higher quality of information than encyclopedias that require single

individuals or an occasional team to cover a broad expanse of information. |

| Plotkin | Even the best scholars are not aware of all developments in their area of

expertise, especially over time. The number of places to publish is expanding, and

it is difficult to keep up with new scholarly information on any

topic. The lack of incentives for spending time on encyclopedia entries also works

against quality, as encyclopedia entries have little weight in the promotional

standards that determine scholars’ advancement and salary. |

| | In addition, the reliance on print for many encyclopedias works as a deterrent

against frequent updates. The costs of issuing a new edition (editorial time,

printing, distribution) are so great that new editions are done at relatively long

intervals, if done at all. Thus, they quickly become out-of-date. |

| Irish | Does Wikipedia offer a model for updating an encyclopedia? |

| Plotkin | No — because of the need for quality assurance (in terms of content and writing),

something that Wikipedia does not yet offer. Citizendium, which dubs itself “a citizen’s compendium of everything,” is another project intended to

add quality standards to an online encyclopedia by attaching names to the

articles. The organizers select editors who are responsible for overseeing

additions. However, I don’t believe that Citizendium will be accepted among scholars in specific disciplines,

because its highest level decision-makers are not specialists in

their disciplines. |

| | Thus, I see the need for the Encyclopedia to develop

an editorial structure that draws on established scholars in urban history. To do

this, the editing of the Encyclopedia will have to

parallel the editing of scholarly journals, i.e, a continuous process. The senior

editors of the Encyclopedia would serve as long as

editors of scholarly journals, with occasional handovers to new editors,

consistent with the experience of scholarly journals. Of course, they will have to

be assisted by a comprehensive network of contributing editors who are specialists

in specific places, time periods, and topics. |

| Irish | It sounds as if the Encyclopedia could really help

reshape the field of urban history. What other innovations would this project

feature? |

| Plotkin | The most important — and the most daunting — is the design of an organizational

structure that will depart from the alphabetical organization favored by most

encyclopedias. Alphabetical organization, with all of its merits, defeats the

possibility of using the vast amount of knowledge collected in scholarly

encyclopedias for comparisons across time, place, and topic. |

| | Let’s take urban transportation, for example. We now have encyclopedias of

Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, and New York City (in the U.S.) and Melbourne, in

Australia, along with any I’ve not listed here. In most of these, entries on urban

transportation are included in alphabetical order, and, unless there is a subject

index, there is no way to identify them. While a subject index is of real value,

its creation is somewhat arbitrary -- and the subject indexes of different

encyclopedias are likely to be different, again defeating easy comparisons. |

| | The goal for the Encyclopedia is to create a

structure of broad categories that will be used for each geographical region, so

that the historical development within that category can be easily compared to

that of other regions. These categories might include transportation, water, food,

energy, shelter, security, order, and creative expression, for example. We have

involved anthropologists in the design of this structure because they are most

familiar with doing broad comparisons over long stretches of time and places. |

| Irish | How is the Encyclopedia related to H-Urban? |

| Plotkin | I believe it is a better way to carry out the mission I had when I established

H-Urban of promoting international and interdisciplinary work. |

| Irish | H-Urban has been vitally important to me since I first joined in 1997: the

stimulating discussion threads, book reviews, and sharing across disciplinary

interests have broadened my research questions. A number of H-Urban editors and

readers are at small colleges in non-urban settings, or in a non-academic

professional setting, and I think the online support they get for their scholarly

interests is invaluable. |

| Plotkin | I agree. However, H-Urban, with its loose structure and lack of serious,

comparative discussion, does not succeed in taking the next step — integrating

scholarly content or ideas, either across space or time. Most historians address

fairly narrow topics, because of the time- intensive nature of historical

research. Without the availability of concise, easy-to-access, information on the

work of other historians, it is difficult to avoid the fragmentation of urban

history that has been so much lamented in the last thirty years. Indeed, this

fragmentation has increased because of the multiplication of journals relating to

urban history and studies, and the increased costs of acquiring journals from

other nations. |

| | When the Internet became available to scholars, others and I hoped that it would

serve to overcome this fragmentation. How to do this well, however, has eluded

H-Urban — and the international urban history community. Discussions on H-Urban

have not thrived because the rewards do not exist to encourage historians to

participate, nor to examine the scholarship on their topic in other geographic

areas. Pressures to publish in formal journals are too great — and most scholars

do not have the time to pursue broader scholarship, save for reading several

journals and attending conferences. While these traditional means of sharing our

research and our findings remain important, they still do not provide a coherent,

international and interdisciplinary framework within which to contextualize one’s

work. |

| | The use of Wikipedia by many of these scholars, in spite of the problems with

quality control, has demonstrated to me that scholars are hungry for a single,

easily accessible place to record and retrieve a large body of information. The

Encyclopedia offers the chance to create such a

place that would be used to summarize the state of the knowledge in urban history

on an ongoing basis, in a form that will facilitate comparisons, overcoming the

fragmentation of urban history that has marked the discipline until the

present. |

| Irish | What is your timeline on the Encyclopedia? |

| Plotkin | I hope to introduce discussion of it on H-Urban in May 2010, and, over the summer,

conduct research on similar attempts to provide on-line, extensible — and, if

available — structured encyclopedias. Hopefully, in the fall, I’ll be able to

submit a proposal to the NEH Digital Start-Up Grant program for funding to develop

a prototype in consultation with leading scholars of urbanism (e.g., history, art

and architectural history, anthropology, architecture, geography, literature,

sociology, urban planning, and urban studies). If funded, and if the Encyclopedia seems feasible as a concept that is

attractive enough to leading scholars to secure their involvement, at the end of

the grant period I’ll organize a team to apply for further funding to create a

foundational version — one that contains enough core knowledge to induce scholars

to augment the existing entries and propose new entries that expand the

geographical or chronological scope of the work. |

| Irish | Could you offer some parting thoughts on digitization of scholarly materials and

the democratization of history? |

| Plotkin | I am glad that you raised this, Sharon, because, up until this point, I have not

really demonstrated a direct connection between my work and community

informatics, in which a key value is the democratization of knowledge. However, I

do believe that they are indirectly connected. |

Let me focus first on the promise of the Internet for democratizing the

production of history. As a fairly traditional academic, I believe in the need for

historians to acquire a broad knowledge of history, the humanities, and the social

sciences, and to combine these with good analytical and writing skills. It takes

time and effort, as well as a good intellect, to acquire this foundation, and even

then, the historian’s skills improve over time.

| Irish | Speedy history is indeed about as good as fast food! |

| Plotkin | Exactly. However, in spite of this continuing reliance on an intellectual elite,

there is a need to expand the pool of those who join this select

group. That is because it is impossible to create a single, enduring, unchallenged

interpretation of history. The difficulty in preserving all evidence of human

existence, and the subjectivity inherent in collecting, organizing, and analyzing

this evidence, make this a pipe dream. For example, in the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, the majority of academic historians (almost all white males)

wrote primarily about elite politics, society, and culture. They deemed this the

only “knowledge” worthy of study, and overlooked the lives and activities of

non-elites — the middle and working classes; racial, ethnic, and religious

minorities; women; and children. It is no coincidence that the democratization of

the academy during the 1960s and 1970s, with increasing numbers of non-elites

entering the historical profession, led to an active interest in the study of

non-elites. |

| | Aside from the social change that expanded the pool of those who became

historians, the growth of technology has had a role in decreasing the importance

of wealth in undertaking what is often very costly historical research. For

example, some scholars have argued that the development of microfilm in the 1930s

reduced the costs of doing historical research. This made it possible for students

and junior scholars to undertake research that would have formerly required costly

travel to libraries and archives. In a similar vein, the creation of on-line

primary and secondary resources have reduced, although not eliminated, the need

for travel and reproduction. |

| Irish | Of course information technologies, whether in the form of microfilm or digital

archives, have changed the way that we do historical research. Different people

ask new and different questions, as you have pointed out. |

| Plotkin | Amen! The Internet has also enhanced the quality of good undergraduate education,

so that students at a state or community college now have access to some of the

same resources that formerly only the elite schools could afford. This

availability also allows individuals who were bored by history in their formal

education to renew their enthusiasm for the field, and for present day students

from K-12 to complement their formal education in a self-directed, interactive

manner. This also has the potential for bringing a wider audience, of a range of

ages and experience, into the discipline of history. |

| Irish | What about the effect of the Internet on those who don’t want to become

historians? |

| Plotkin | In some ways, this is even more important, because all of us are citizens, even if

we are not historians. One of the requirements for being a good citizen is being

well informed in history as well as current events. And this has not always been

easy in the past. Individuals have a variety of learning styles, but traditional

education has tended to rely on a single style, emphasizing lecture, reading, and

writing. The Internet offers not only an easier and

cheaper way to disseminate information, but also a greater variety

of methods of presenting it. |

| | The use of visuals enhances the understanding of history, as David Staley

discusses in his book [Staley 2002]. It is not, as some critics

argue, an anti-intellectual concession to the “visual” generation. The

integration of text, visuals, and hypertext can offer a less forbidding means of

learning history than in the past, making it available to many more individuals.

Online discussion forums such as H-Urban and COMM-ORG can answer questions that

students previously were discouraged from asking teachers. Overall, the Internet

has become part of the solution to making the study of history more appealing to

individuals from all walks of life and with various levels of formal

education. |

| | All of this is for the good, because, as I said above, knowledge of history is

essential to becoming an informed citizen. Whether it is learning about the

history of exclusionary zoning and redlining or reading the minutes of the

planning board of one’s town, the easy availability of this information can make

us all more engaged citizens. |

| Irish | Let me take this opportunity to thank you, Wendy, for your engaged scholarship and

incomparable dedication to urban history, online and off. |

| Plotkin | And let me thank you, Sharon, for the time and excellence you have contributed to

H-Urban and other scholarly enterprises. |

Notes

[1] In the late 1970s, the administration of President Jimmy

Carter provided funding to regional planning agencies under two initiatives —

the Areawide Housing Opportunity Program and the Regional Housing Mobility

Program — to promote fair and affordable housing in the nation’s metropolitan

regions. The goal of the program was to promote “deconcentration” of

racial minorities from the inner cities to the suburbs. My supervisor was a

former community organizer who was opposed to moving African-American residents

out of the inner city into the suburbs. While opening up the suburbs to African

Americans and other racial minorities was an admirable objective, in the

absence of similar initiatives to allow them to stay in improved neighborhoods

in the city, it looked a lot like the “Negro removal” of the urban renewal

programs of the 1950s, at a time when the energy crisis was encouraging white

gentrification. Staff from regional housing agencies around the country

convinced HUD to change the interpretation of the statutory language of the

Regional Housing Mobility Program so that, instead of encouraging movement from

their neighborhoods, the funds could be used to revitalize the neighborhoods.

Watching my supervisor’s participation in these negotiations with HUD, I

learned the importance of advocacy and personal contact in shaping how the

government implements (or does not implement) legislation, a lesson on the

informal processes that affect governance.

[2] The Boston Housing Partnership was an umbrella program to garner

resources and assist ten community development corporations in rehabilitating

and managing a total of 1000 units of multifamily housing in their

neighborhoods. The former director, Robert Whittlesey, is now the director of a

larger organization, the Housing Partnership Network (http://www.housingpartnership.net). The history of the Network is

described at http://www.housingpartnership.net/about_us/history/. [3] The CEED program no longer exists.

[4]

Urban Planning Aid, Less Rent, More Control: A Tenants

Guide to Rent Control in Massachusetts (Cambridge: Urban Planning

Aid, 1972).

[5] Emily Achtenberg and Michael Stone, Tenants

First! A Research and Organizing Guide to FHA Housing (Cambridge:

Urban Planning Aid, 1974) and Urban Planning Aid, How to

Use OSHA (Cambridge: Urban Planning Aid, 1975). The records of Urban

Planning Aid, which closed its doors in 1982, are at the University of

Massachusetts at Boston (described at http://www.lib.umb.edu/node/1645). Among those who have assessed

their work is Lily M. Hoffman, The Politics of Knowledge:

Activist Movements in Medicine and Planning (Albany: SUNY,

1986). [7] It did

this by creating a “mark-up” system that would characterize not only the

physical content of texts (e.g. title, body, headings), but also the

intellectual content (e.g. date, place, war). On the TEI, see http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml. [8] Richard Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and

Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1971). In his review for the American Historical

Review, Lewis Gould described the work as “superub” and wrote, “Well

written and closely reasoned, The Winning of the

Midwest brilliantly combines the techniques of the social

scientist and the historian to produce a convincing narrative of

developments in the principal regional background of partisan conflict at

the end of the nineteenth century.” Lewis I. Gould, “New Perspectives on the Republican Party, 1877-1913,”

American Historical Review 77:4 (Oct., 1972),

1074-1082. Quote on 1076-77. Jensen is routinely included as one of the

pioneers of the “ethnocultural” school in the historical literature; see,

for example, “The Invention of the Ethnocultural

Interpretation,”

American Historical Review 99:2 (April, 1994),

453-477, especially 460-463.

[9] For the evolution in Jensen’s thoughts on the qualitative

uses of the computer among historians, see Richard Jensen, “Historians and Computers: Word Processing,”

OAH Newsletter (1983), 11:2, 15-16; Richard

Jensen, “The Hand Writing on the Screen,”

Historical Methods 20:1 (Winter, 1987), 35-45; and

Richard Jensen, “Text Management” (Review), Journal of Interdisciplinary History 22:4 (Spring,

1992), 711-722.

[11]

The Internet emerged from systems developed by the Defense Advanced Research

Projects Agency (DARPA), within the Department of Defense starting in the

1960s. These systems were initially set up to allow scientists to exchange

large electronic files, but the convenience of exchanging short messages was

discovered immediately. The initial civilian system — ARPANET — sent its

first message in 1969, but much work remained to develop the physical and

systems infrastructure to embrace an entire nation. See Barry M. Leiner et

al., “All About the Internet: History of the

Internet,” at http://www.isoc.org/internet/history/brief.shtml.

For the most part, humanities scholars did not begin to use these systems

until the mid-1980s, a decade before the term Internet was

adopted for what was, by then, far more seamless and user-friendly than in

its early days. Textbook publishers were among the earliest funders of

humanities networks, hoping to obtain better information for planning

purposes. Among academicians, classicists and literary/linguistic scholars

were among the first to use this new tool for group communication, with the

creation of Humanist and the Bryn Mawr Classical Review (BMCR, which only

distributed book reviews). In 1985, the “Whole Earth

‘Lectronic Link” (WELL) brought together “authors, programmers, journalists,

activists and other creative people” to communicate online (http://www.well.com/). At the same

time,Professor Lynn Nelson at Kansas State University and others started the

first history discussion lists, including Mediev-L, History-L, and HAPSBURG.

These lists, while containing some valuable content, did not screen messages

or limit their subscriptions to scholars, and were liable to more casual use

by amateur historians. For early articles about the Internet and history

discussion groups, see Richard W. Slatta, “Historians

and Telecommunications,”

History Microcomputer Review 2:2 (Fall 1986):

25–34; David R. Campbell, “The New History Net,”

History Microcomputer Review 3:2 (Fall 1987):

25; and Norman R. Coombs, “History by

Teleconference,”

History Microcomputer Review 4:1 (Spring 1988):

37–40.

[12] Among the pieces attacking the type of gatekeeping

practiced by H-Net, see Jesse Lemisch, “The First Amendment

is Under Attack in Cyberspace,”

Chronicle of Higher Education, 41:19, January 20,

1995, A56. For a more recent discussion of the topic, see Thomas W. Zeiler,

“Is Democracy a Good Thing?”

OAH Council of Chairs Newsletter 34 (November

2006), at http://www.oah.org/pubs/nl/2006nov/zeiler.html. On the debate over

requiring authors of posters to identify themselves, see Lisa Guernsey, “Scholars Debate the Pros and Cons of Anonymity in Internet

Discussions,”

Chronicle of Higher Education, 43:6, October 4,

1996, A23-24. See Melvin E. Page, “Editing an H-Net

Discussion List,”

OAH Newsletter 52 (August 1996), at http://www.h-net.org/about/press/oah/page.html for a thoughtful

overview of the stylistic issues associated with H-Net editing. [14] An early description of H-Net’s website is

Mark Lawrence Kornbluh, “The H-Net Website: Designing

OnLine Resources for Scholars and Teachers,”

OAH Council of Chairs Newsletter, 52 (August

1996), at http://www.h-net.org/about/press/oah/web.html. On the H-Net Book

Review project, see Patricia Lee Denault, “The H-Net Review

Project,”

OAH Council of Chairs Newsletter 52 (August 1996),

at http://www.h-net.org/about/press/oah/essaybr.html. On H-Net’s

teaching rsources, see Sara Tucker and Robert Wheeler, “H-Net and the Classroom: H-Teach,”

OAH Council of Chairs Newsletter 52 (August 1996),

at http://www.h-net.org/about/press/oah/teach.html. [15] Clay McShane is a professor at Northeastern University, and a

historian of urban technology, with landmark books Down

the Asphalt Path: American Cities and the Automobile (Columbia,

1994) and The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the

Nineteenth Century (Johns Hopkins University, 2007). Roger Biles is

a professor at Illinois State University, and the author of numerous books,

including Richard J. Daley: Politics, Race, and the

Governing of Chicago (Northern Illinois University, 1995) and Crusading Liberal: Paul H. Douglas of Illinois

(Northern Illinois University Press, 2002).

[17] See “Wikiality,” Stephen Colbert’s satirical monologue on

Wikipedia, at http://www.comedycentral.com/colbertreport/videos.jhtml?videoId=72347.

There is a growing scholarly literature on Wikipedia; among the most thoughtful

by a historian, see Roy Rosenzweig, “Can History Be Open

Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past,”

Journal of American History 93:1 (June, 2006),

117-146. Works Cited

Achtenberg & Stone 1974 Emily Achtenberg and Michael Stone, Tenants First! A Research

and Organizing Guide to FHA Housing. Cambridge: Urban Planning Aid,

1974.

Guernsey 1997 Lisa Guernsey,

“Election Campaign to Run H-Net, A Popular Network of E-Mail

Lists, Turns Nasty,”

Chronicle of Higher Education, 43:32, April 18, 1997,

A25.

Hoffman 1986 Lily M. Hoffman,

The Politics of Knowledge: Activist Movements in Medicine and

Planning. Albany: SUNY, 1986.

Jensen 1971 Richard Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict,

1888-1896. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

Jensen 1983 Richard Jensen, “The Accomplishments of the Newberry Library Family and Community

History Programs: An Interview with Richard Jensen,”

The Public Historian 5:4 (August 1983), 49-61.

Plotkin 2003 Wendy Plotkin, “Electronic Texts in the Historical Profession: Perspectives from

Across the Scholarly Spectrum,” in Orville Vernon Burton, ed., Computing in the Social Sciences and Humanities. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, March 2003.

Staley 2002 David J. Staley, Computers, Visualization, and History: How New Technology Will

Transform Our Understanding of the Past. M.E. Sharpe, 2002.

Urban Planning Aid 1972 Urban Planning

Aid, Less Rent, More Control: A Tenants Guide to Rent Control in

Massachusetts. Cambridge: Urban Planning Aid, 1972.

Urban Planning Aid 1975 Urban Planning

Aid, How to Use OSHA. Cambridge: Urban Planning Aid,

1975.

Young 2009 Jeffrey R. Young, “Change or Die: Scholarly E-Mail Lists, Once Vibrant, Fight for

Relevance,”

Chronicle of Higher Education, June 25, 2009.