Abstract

As digital humanists have adopted visualization tools in their work, they have borrowed

methods developed for the graphical display of information in the natural and social

sciences. These tools carry with them assumptions of knowledge as observer-independent and

certain, rather than observer co-dependent and interpretative. This paper argues that we

need a humanities approach to the graphical expression of interpretation. To begin, the

concept of data as a given has to be rethought through a humanistic lens and

characterized as capta, taken and constructed. Next, the forms for graphical

expression of capta need to be more nuanced to show ambiguity and complexity. Finally, the

use of a humanistic approach, rooted in a co-dependent relation between observer and

experience, needs to be expressed according to graphics built from

interpretative models. In summary: all data have to be understood as capta and the

conventions created to express observer-independent models of knowledge need to be

radically reworked to express humanistic interpretation.

Introduction

As digital visualization tools have become more ubiquitous, humanists have adopted many

applications such as GIS mapping, graphs, and charts for statistical display that were

developed in other disciplines. But, I will argue, such graphical tools are a kind of

intellectual Trojan horse, a vehicle through which assumptions about what constitutes

information swarm with potent force. These assumptions are cloaked in a rhetoric taken

wholesale from the techniques of the empirical sciences that conceals their

epistemological biases under a guise of familiarity. So naturalized are the Google maps

and bar charts generated from spread sheets that they pass as unquestioned representations

of “what is”. This is the hallmark of realist models of knowledge and needs to be

subjected to a radical critique to return the humanistic tenets of constructed-ness and

interpretation to the fore. Realist approaches depend above all upon an idea that

phenomena are

observer-independent and can be characterized as

data. Data pass themselves off as mere descriptions of a priori conditions.

Rendering

observation (the act of creating a statistical, empirical, or subjective account

or image) as if it were

the same as the phenomena observed collapses the

critical distance between the phenomenal world and its interpretation, undoing the basis

of interpretation on which humanistic knowledge production is based. We know this. But we

seem ready and eager to suspend critical judgment in a rush to visualization. At the very

least, humanists beginning to play at the intersection of statistics and graphics ought to

take a detour through the substantial discussions of the sociology of knowledge and its

developed critique of realist models of data gathering

[1]

At best, we need to take on the challenge of developing graphical expressions rooted in

and appropriate to interpretative activity.

Because realist approaches to visualization assume transparency and equivalence, as if

the phenomenal world were self-evident and the apprehension of it a mere mechanical task,

they are fundamentally at odds with approaches to humanities scholarship premised on

constructivist principles. I would argue that even for realist models, those that presume

an observer-independent reality available to description, the methods of presenting

ambiguity and uncertainty in more nuanced terms would be useful. Some significant progress

is being made in visualizing uncertainty in data models for GIS, decision-making,

archaeological research and other domains.

[2] But an important

distinction needs to be clear from the outset: the task of representing ambiguity and

uncertainty has to be distinguished from a second task – that of using interpretations

that arise in observer-codependence, characterized by ambiguity and uncertainty, as the

basis on which a representation is constructed. This is the difference between putting

many kinds of points on a map to show degrees of certainty by shades of color, degrees of

crispness, transparency etc., and creating a map whose basic coordinate grid is

constructed

as an effect of these ambiguities. In the first instance, we have

a standard map with a nuanced symbol set. In the second, we create a non-standard map that

expresses the constructed-ness of space. Both rely on rethinking our approach to

visualization and the assumptions that underpin it.

To overturn the assumptions that structure conventions acquired from other domains

requires that we re-examine the intellectual foundations of digital humanities, putting

techniques of graphical display on a foundation that is humanistic at its base. This

requires first and foremost that we reconceive all data as capta. Differences in

the etymological roots of the terms data and capta make the distinction between

constructivist and realist approaches clear. Capta is “taken” actively while

data is assumed to be a “given” able to be recorded and observed. From this

distinction, a world of differences arises. Humanistic inquiry acknowledges the situated,

partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that

knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation

of pre-existing fact.

My distinction between data and capta is not a covert suggestion that the humanities and

sciences are locked into intellectual opposition, or that only the humanists have the

insight that intellectual disciplines create the objects of their inquiry. Any

self-conscious historian of science or clinical researcher in the natural or social

sciences insists the same is true for their work. Statisticians are extremely savvy about

their artifices. Social scientists may divide between realist and constructivist

foundations for their research, but none are naïve when it comes to the rhetorical

character of statistics. The history of knowledge is the history of forms of expression of

knowledge, and those forms change. What can be said, expressed, represented in any era is

distinct from that of any other, with all the attendant caveats and reservations that

attend to the study of the sequence of human intellectual events, keeping us from any

assertion of progress while noting the facts of change and transformation. The historical,

critical study of science is as full of discussions of this material as the

humanities.

Thus the representation of knowledge is as crucial to its cultural force as

any other facet of its production. The graphical forms of display that have come to the

fore in digital humanities in the last decade are borrowed from a mechanistic approach to

realism, and the common conception of data in those forms needs to be completely rethought

for humanistic work. To reiterate what I said above, the sheer power of the graphical

display of “information visualization” (and its novelty within a humanities community

newly enthralled with the toys of data mining and display) seems to have produced a

momentary blindness among practitioners who would never tolerate such literal assumptions

in textual work.

The polemic I set forth here outlines several basic principles on which to proceed

differently by suggesting that what is needed is not a set of applications to

display humanities “data” but a new approach that uses humanities principles to

constitute capta and its display. At stake, as I have said before and in many

contexts, is the authority of humanistic knowledge in a culture increasingly beset by

quantitative approaches that operate on claims of certainty. Bureaucracies

process human activity through statistical means and when the methods grounded in

empirical sciences are put at the service of the social sciences or humanities in a

crudely reductive manner, basic principles of critical thought are violated, or at the

very least, put too far to the side. To intervene in this ideological system, humanists,

and the values they embrace and enact, must counter with conceptual tools that demonstrate

humanities principles in their operation, execution, and display. The digital humanities

can no longer afford to take its tools and methods from disciplines whose fundamental

epistemological assumptions are at odds with humanistic method.

This paper is a call to imaginative action and intellectual engagement with the challenge

of rethinking digital tools for visualization on basic principles of the humanities. I

take these principles to be, first, that the humanities are committed to the concept of

knowledge as interpretation, and, second, that the apprehension of the phenomena of the

physical, social, cultural world is through constructed and constitutive acts, not

mechanistic or naturalistic realist representations of pre-existing or self-evident

information. Nothing in intellectual life is self-evident or self-identical, nothing in

cultural life is mere fact, and nothing in the phenomenal world gives rise to a record or

representation except through constructed expressions. The rhetorical force of graphical

display is too important a field for its design to be adopted without critical scrutiny

and the full force of theoretical insight. Let me suggest what that means for the

visualization of informational, temporal, and spatial phenomena.

Data as capta: from information visualization to graphical expressions of

interpretation

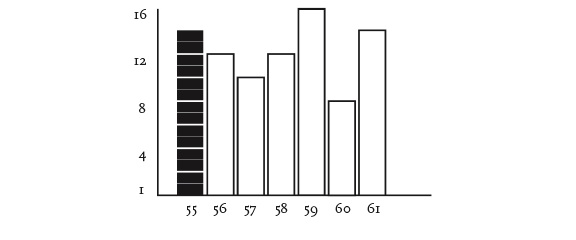

If I set up a bar chart or graph, my first act is to draw a set of one or more axes and

divide them into units. The conventional forms of the graphical display of information,

“data”, make use of a formal, unambiguous system of standard metrics. Charts use simple

(if often misleading) geometric forms that lend themselves to legible comparison of

values, proportions, or the exhibition of state changes across time. Lines, bars, columns,

and pie charts are the common and familiar forms. They render quantitative

relations with a transparency that seems natural, so that, for instance, if we look at the

changes in population across a series of years for a particular location, we can simply

accept that from one year to the next rises or drops occurred in the numbers of persons

alive in X city in X country at X time. A pie chart showing percentage of resource

allocation from national budgets seems completely transparent, self-evident even. A bar

chart could compare daylight hours at different longitudes, or the average size of men and

women in different countries, or the number of hospital beds in different institutions in

a single geographical location and not raise a skeptical eyebrow, right? Yes, but the

rendering of statistical information into graphical form gives it a simplicity and

legibility that hides every aspect of the original interpretative framework on which the

statistical data were constructed. The graphical force conceals what the statistician

knows very well — that no “data” pre-exist their parameterization. Data

are capta, taken not given, constructed as an interpretation of the phenomenal

world, not inherent in it.

To expose the constructedness of data as capta a number of systematic changes have to be

applied to the creation of graphical displays. That is the foundation and purpose of a

humanistic approach to the qualitative display of graphical information.

Read that last formulation carefully, humanistic approach means that the

premises are rooted in the recognition of the interpretative nature of

knowledge, that the display itself is conceived to embody qualitative

expressions, and that the information is understood as graphically

constituted. Each of these factors contains an explicit critique of assumptions

in the conventional “visual display of quantitative information” that is the common

currency.

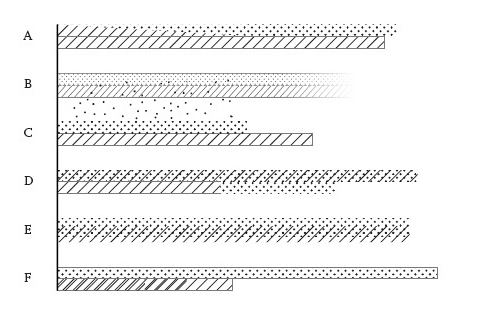

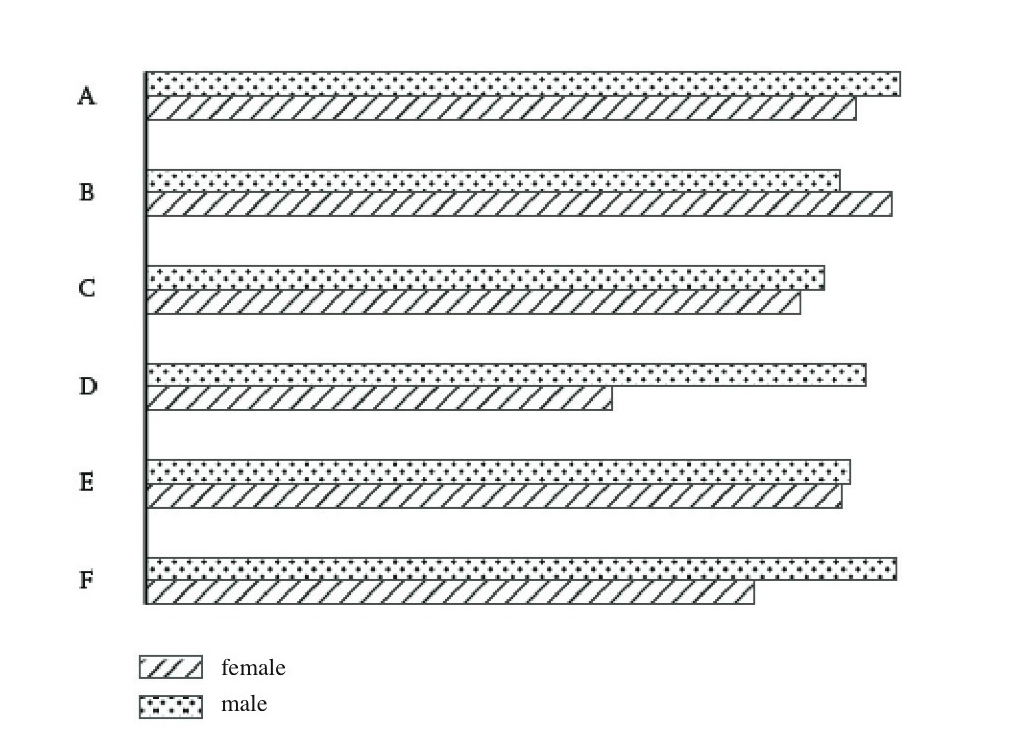

Let me work through a specific case to show how each of these principles —

humanistic approach, qualitative display, and graphical information — can be

demonstrated. As an example, we can use that bar chart mentioned above, one that compares

the percentage of men and women in various national populations at the present time.

Certain issues immediately arise. A standard critique of data introduces reservations

about the appearance of certainty such a chart presents. What counts as a nation? Are

transient and immigrant populations documented? What kind of time span counts as “at the

present time” within which these populations are counted? If the basic bar chart would

have looked like a series of bands showing discrete categories of information in finite

and certain numbers (all due statistical caveats noted), what are the problems? Gender

definition assumes a simple binary distinction of men and women, an assumption much

debated and highly problematic (gender can be understood as a factor of behavior,

physiological changes, social expectations, dress, etc., and nation as a function of

permeability of borders, citizenship patterns, naturalization rules, immigration

regulations, quotas and border policies). So the bar chart reifies several categories,

naturalizing them as discrete and fixed: national populations, time span, and gender

defined as a simple binary. The representation can only be modified by changing the terms

and premises on which it is constructed. What would a representation of gender by sliding

scale look like? How would permeable boundaries to nations whose populations cross each

others borders be shown? How would they dissolve the bar chart’s basic structure? How

would notions of the present be defined?

The point I’m making is that the basic categories of supposedly quantitative information,

the fundamental parameters of chart production, are already interpreted expressions. But

they do not present themselves as categories of interpretation, riven with ambiguity and

uncertainty, because of the representational force of the visualization as a

“picture” of “data”. For instance, the assumption that gender is a binary category, stable

across all cultural and national communities, is an assertion, an argument. Gendered

identity defined in binary terms is not a self-evident fact, no matter how often Olympic

committees come up against the need for a single rigid genital criterion on which to

determine difference. By recognizing the always interpreted character of data we have

shifted from data to capta, acknowledging the constructed-ness of the categories according

to the uses and expectations for which they are put in service. Nations, genders,

populations, and time spans are not self-evident, stable entities that exist a priori.

They are each subject to qualifications and reservations that bear directly on and arise

from the reality of lived experience. The presentation of the comparison in the original

formulation grotesquely distorts the complexity — but also, the basic ambiguity

— of the phenomenon under investigation (gender, nations, populations). If the

challenge we are facing were merely to accommodate higher levels of complexity into a data

representation model, that would require one set of considerations and modifications. But

the more profound challenge we face is to accept the ambiguity of knowledge, the

fundamentally interpreted condition on which data is constructed, in other words, the

realization of my refrain–that all data is capta.

The humanistic aspect of this approach should be obvious — that knowledge

created with the acknowledgement of the fundamentally constructed nature of its premises

is not commensurate with principles of certainty guiding empirical or realist methods.

Humanistic methods are counter to the idea of reliably repeatable experiments or standard

metrics that assume observer independent phenomena. By definition, a humanistic approach

is centered in the experiential, subjective conditions of interpretation. Phenomena and

their observers are co-dependent, not necessarily in equal measure. A viewer gazing on a

sublime landscape or recording migrations at a large scale may be more affected by the

phenomena than the phenomena is by the observation. Theoretical physicist Werner

Heisenberg never suggested that the relation of intervening observer and effect on

phenomena were symmetrical, merely that they were codependent, when he introduced the

concept of uncertainty in the early 20th century.

Creating bar charts with ambiguity and degrees of uncertainty or other variables in them

might cause champions of legibility and transparency some unease, but the shift away from

standard metrics to metrics that express interpretation is an essential move for humanists

and/or constructivists across disciplines. To emphasize the expressive quality of

interpretation, I’m going to characterize constructed information as

subjective – expressing the marks of its inflection in some formal way. The

shift to expressive metrics and graphics is essential in changing from the

expression of subjective information to the

subjective expression of

perceived phenomena, but subjectivity and inflection are not the only features of

interpretative approaches. Capta is not an expression of idiosyncracy, emotion, or

individual quirks, but a systematic expression of information understood as constructed,

as phenomena perceived according to principles of interpretation. To do this, we need to

conceive of every metric “as a factor of X”, where X is a point of view, agenda,

assumption, presumption, or simply a convention. By qualifying any metric as a factor of

some condition, the character of the “information” shifts from self-evident

“fact” to

constructed interpretation motivated by a human agenda.

[3]

The standard elements of graphic display for statistical information are simple and

limited: scale divisions, coordinate lines, scale figures, circles, rectangles, curves,

bars (or columns or percentages of pie charts or other forms) and labels (numbers and

terms), signs of movement, flow, or state change (arrows, vectors, paths). The ordering

and arrangement of elements within a chart create another level of information, relational

information. Relational information is graphically produced – the ordering of elements by

size, by color, by alphabetical order, by texture, shape or other feature happens in

graphical space. The resulting arrangement has a semantic value produced by features of

proximity, grouping, orientation, apparent movement, and other graphical effects.

Now take these basic elements of graphical display and rethink them according to

humanistic principles:

In conventional statistical graphics, the scale divisions are equal units. In humanistic,

interpretative, graphics, they are not.

In statistical graphics the coordinate lines are always continuous and straight. In

humanistic, interpretative, graphics, they might have breaks, repetitions, and curves or

dips. Interpretation is stochastic and probabilistic, not mechanistic, and its

uncertainties require the same mathematical and computational models as other complex

systems.

The scale figures and labels in statistical graphics need to be clear and legible in all

cases, and all the more so in humanistic, interpretative, graphics since they will need to

do quite a bit of work.

Perhaps the most striking feature distinguishing humanistic, interpretative, and

constructivist graphical expressions from realist statistical graphics is that the curves,

bars, columns, percentage values would not always be represented as discrete bounded

entities, but as conditional expressions of interpretative parameters–a kind of visual

fuzzy logic or graphical complexity. Thus their edges might be permeable, lines dotted and

broken, dots and points vary in size and scale or degree of ambiguity of placement, and so

on. These graphical strategies express interpreted knowledge, situated and partial, rather

than complete. They can be employed as systematically as other charting elements, though

part of my intention is to disturb the grounds of certainty on which conventions of

statistical legibility are based. Point of view systems introduced into graphs and charts

will make evident a perspectival position with respect to their information, an inner

standing point in the graphical rendering of space. This is true of all cartographic

projections. Every map contains within its coordinate system for graphical expression, a

set of assumptions about the place from which the map is drawn. Information spaces drawn

from a point of view, rather than as if they were observer independent, reinsert the

subjective standpoint of their creation into the graphical expression. Finally, any point

or mark used as a specific node in a humanistic graph is assumed to have many dimensions

to it – each of which complicates its identity by suggesting the embedded-ness of its

existence in a system of co-dependent relations. Information entities, or units, are thus

understood as fictional abstractions serving a purpose. But their potential to be read

again in relation to any number of other equally significant relations can be made

evident. This approach destroys the ground on which standard metrics are used to abstract

quantitative information from human circumstances. Humanistic premises replace notions of

statistical concepts of self-identity with entangled co-dependence and contingencies.

All of this may sound unduly complicated to someone merely wanting to count the number of

pupils enrolled in a group, calculate the number of pencils needed, or to show budgetary

expenditures on a per capita basis in the classroom, for example. But this example

— an instance of administrative and bureaucratic management — shows

that such crudely conceived numeric statistics are useful only in the most reductive

circumstances. They tell us nothing about whether the pencils can be used, whether the

pupils are prepared or disposed to their work, or whether the budgets will have any effect

on learning outcomes or any of the many other factors that come into play in assessments

based on metrics extracted from lived experience. But each metric — number of X

or Y — is actually a number as a factor of a particular intellectual assumption

or decision: pupils as a factor of seats in a room, birthdates, population, illness, etc.

pencils as a factor of resource allocation, and so on. All metrics are metrics about

something for some purpose.

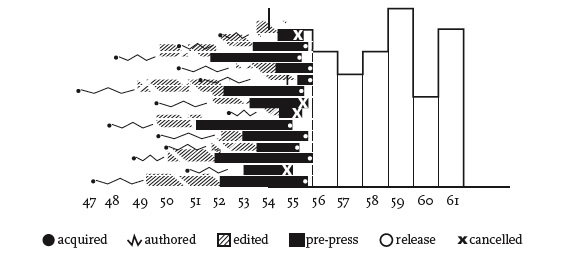

Any humanistic study based on statistical methods, even the simplest techniques of

counting, has to address the assumption involved in the categories on which such

techniques (“how many of X”) are based. Take another example from work in data mining or

“distant reading” as it is known in the digital humanities: counting the number of novels

published in a given year. This involves an enormous number of interpretative decisions –

each of which has more intellectual dimensions than any numeric assessment could.

For instance, what is a novel, what does “published” mean in this context (date of

appearance, editing, composition, acquisition, review, distribution), and how was the

“year” determined. Statistical methods come into play after these decisions

have been made, counting objects whose identity was established by interpretative

decisions. Many aspects of constructed-ness are in play. But the graphical

presentation of supposedly self-evident information (again, formulated in this example as

“the number of novels published in a year”) conceals these complexities, and the

interpretative factors that bring the numerics into being, under a guise of graphical

legibility. I cannot overstate the perniciousness of such techniques for the effect of

passing construction off as real, and violating the very premises of humanistic

inquiry.

The challenge is to design graphical expressions suited to the display of interpreted

phenomena: information about subjective user-dependent metrics,

subjective displays of information, and subjective methods of

graphical expression. The term subjective is used as shorthand for interpretative

construction, for the registration of point of view, position, the place from which and

agenda according to which parameterization occurs. Subjectivity is not the same as

individual inflection or mere idiosyncracy, but is meant to put codependent relations of

observer and phenomena (in contrast to presumptions of objectivity, or

observer-independent phenomena).

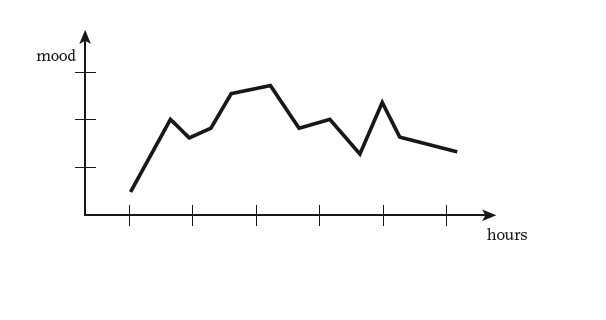

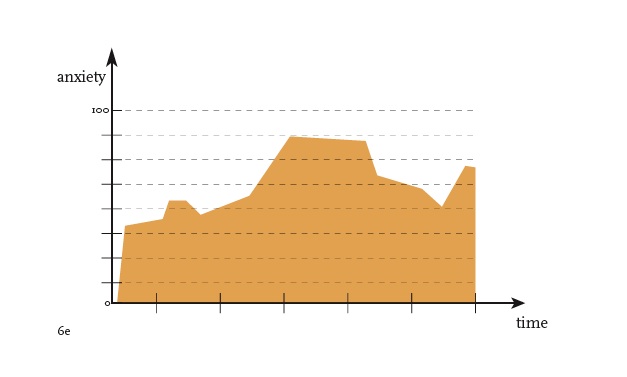

The display of information about inflection of affective experience can easily use

standard metrics. For example, a chart that shows mood changes or degrees of attraction or

any other information related to subjectivity can be created with standard metrics and

visual conventions.

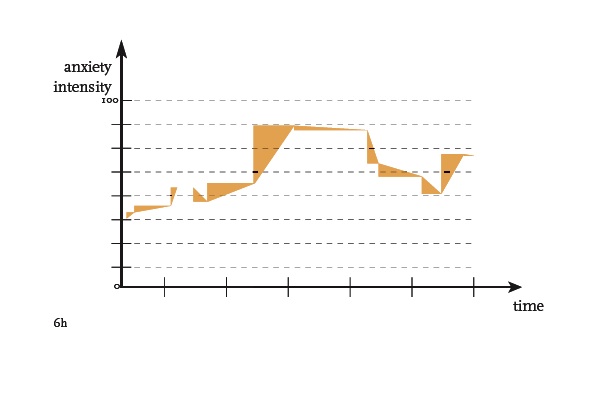

The next task is more complicated. Subjective information, that is information whose

constitution exhibits its subjective character, deviates from the standard norms by using

graphic variables such as intensity of tone, size, color, or other feature to embody its

qualities. Subjective information can use graphical means to show its inflected character,

demonstrating its deviation from standard norms in the way the display looks, or, in

dynamic displays, the way it acts. One might imagine skittish points on an

unstable grid to display the degrees of anxiety around a particular event or task, for

instance, or points that glow hot or cold depending on the other elements that approach

them. That would be a subjective — even affective — display of

information.

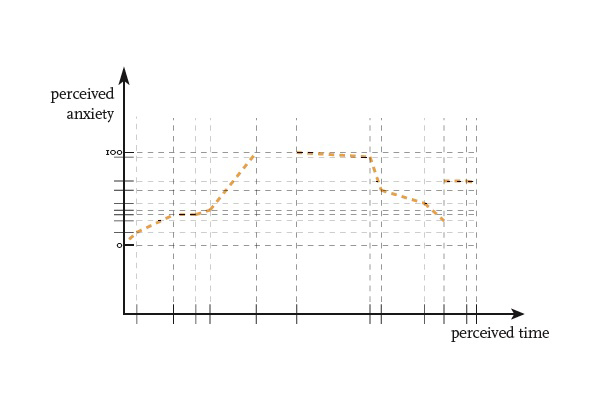

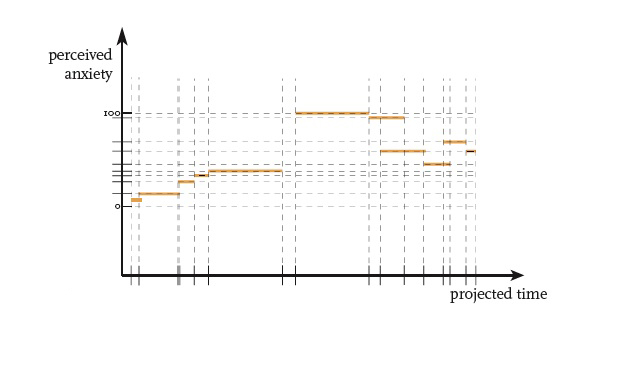

Creating a display whose structure arises from subjective methods of

graphical expression extends this last example to the design of the basic visual

structure.

A subjective grid to show anxiety might have a widely varying set of spacings to show

that the information on display is constituted as a variable of some other aspect of

experience (number of family members present at an event, for instance). Recognizing that

such subjective methods are anathema to the empirically minded makes me even more

convinced that they are essential for the generation of graphical displays of

interpretative and interpreted information.

The basic principle underlying such graphical displays is that capta marks its

interpreted status. Interpreted knowledge is situated, observer co-dependent, and partial.

Its variables are, in theory, infinite, but they are always present in some degree or

measure by virtue of the performative and participatory character of interpretative

information. Interpretation depends upon and is an expression of an individual reading in

a particular set of circumstances and never presumes to completeness or observer

independence. The requirements for legibility increase with these unfamiliar graphics, and

they will need labeling to make explicit the justifications for their non-normative

seeming appearance. I’m not advocating idiosyncracy, or intellectual solipsism, but a

systematic approach to graphics that is appropriate to its principles.

These humanistic principles can be readily applied to the graphical display of temporal

and spatial information. So I will turn my attention in these next two sections to some of

the principles on which temporality and spatiality can also be given graphical expression

through humanistic approaches.

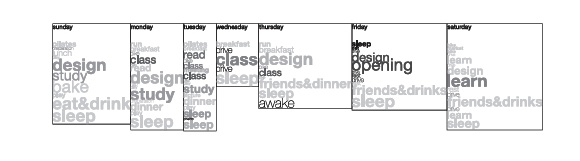

Time as Temporality

Since antiquity, human conceptions of time have divided between those that consider time

a given, an a priori existing container within which events occur, and those who consider

time an effect of occurrences in temporal relation to each other. I take the latter view.

The relational structure of temporality is always constituted according to inflections and

variables. Not all days are equal. Or all minutes. Or all hours. Time understood as

temporality can be succinctly stated as follows: Temporality = time as a factor of

X where X is any variable (fear, speed, anxiety, foreshadowing,

regret, reconsideration, narration, etc.).

Humanists deal with the representation of temporality of documents (when

they were created), in documents (narrated, represented, depicted

temporality), the construction of temporality across documents (the

temporality of historical events), and also the shape of temporality that emerges

from documentary evidence (the shape of an era, a season, a period or

epoch). They need a way to graph and chart temporality in an approach that suits the basic

principles of interpretative knowledge.

Conceptions of temporality in humanities documents do not conform to those used in the

social and empirical sciences. In empirical sciences, time is understood as continuous,

uni-directional, and homogenous. Its metrics are standardized, its direction is

irreversible, and it has no breaks, folds, holes, wrinkles, or reworkings. But in the

humanities time is frequently understood and represented as discontinuous,

multi-directional, and variable. Temporal dimensions of humanities artifacts are often

expressed in relational terms – before such and such happened, or after a significant

event. Retrospection and anticipation factor heavily in humanistic works, and the models

of temporality that arise from historical and literary documents include multiple

viewpoints.

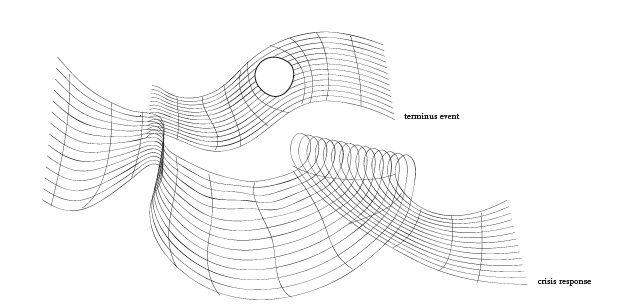

The temporal modeling project Bethany Nowviskie and I designed almost ten years ago made

use of these basic insights in order to create a graphical application that was the

working proof of a concept. We were intent on demonstrating that a graphical model could

be created intuitively as an interpretation and then used to generate structured data as a

result. Inverting the sequence of intellectual events was a radical move for digital

humanities, especially at the time, suggesting that graphical knowledge could be primary,

leading an interpretation, rather than always and only functioning to display what was

already known (or assumed to be known). We wanted to demonstrate that visual spaces could

be a primary site of intellectual work. Of course, that added yet another level of

unfamiliarity to our already complex project – and many even in our immediate community

were unsettled by elastic or stretchy timelines, multiple points of view from within the

system, or other novel seeming conventions meant to serve for interpretation of literary

and historical artifacts.

Briefly summarized, the original Temporal Modelling project aimed at creating a set of

conceptual primitives for the modeling of temporal relations. These included graphical

expressions meant to meet the needs of multiple points of view, reworking events according

to a changed position within a temporal sequence, and a set of what we called inflections.

Inflections, a kind of legend for marking points, intervals, or events (our basic units)

with a quality or attribute, were divided into semantic and syntactic types. Semantic

inflections were given their characteristics independently, as entities, and the

vocabulary of attributes included degrees of intensity and other qualities. Syntactic

inflections were characterized as relational, marking the effect of one event, point, or

interval or another.

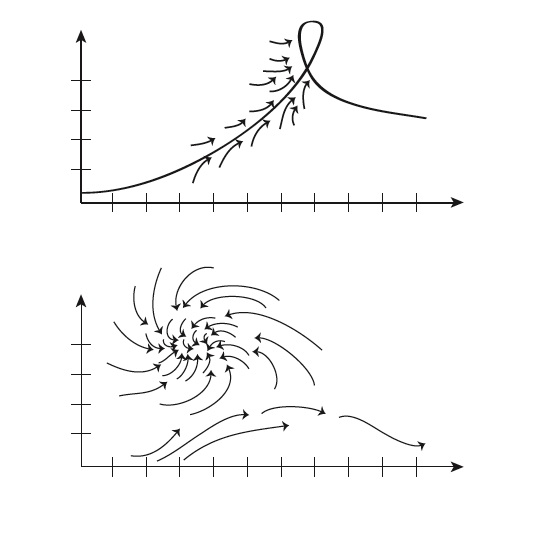

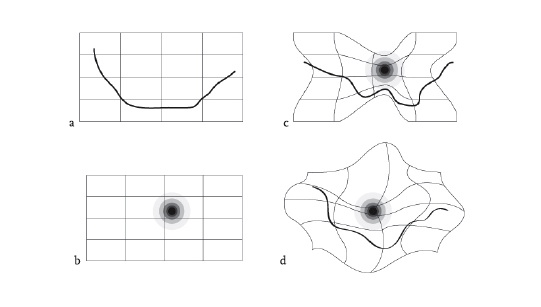

Methods for graphing the elastic or “rubber-sheet” timelines meant to show the subjective

variations in temporality can be derived from catastrophe theory, chaos diagrams, and the

visualizations of stochastic and complex systems.

These visualizations express the topological and systemic complexity necessary

to model the number of variables (of coordinates, forces, and the changing relations of

variables) present in the experience of events, and/or analysis of their representation in

humanistic documents (e.g. novels, films, letters, etc.). Some of the features of our

earlier design, such as the dynamic behaviors of syntactic relations, could not be

expressed in a standard Cartesian coordinate system (such as the one on which XML output

is generated), even though dynamic and performative syntactic relations can be made

operational by using vectors or forces.

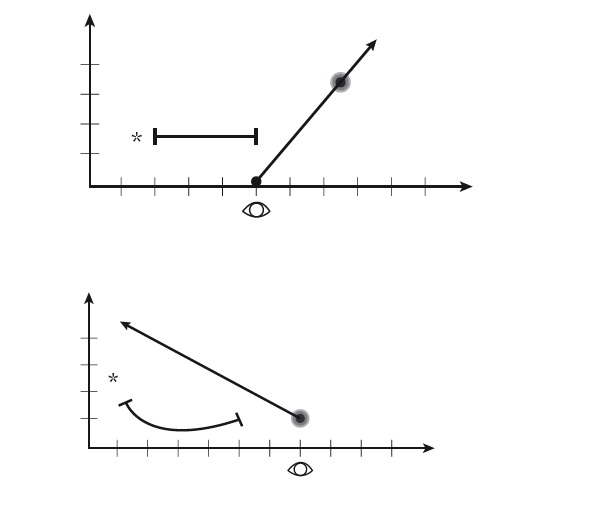

But even standard coordinate systems, such as the conventions of perspectival

drawing, allow for the interpretative quality temporal experience to be expressed more

fully than is possible with standard timelines. A parallax view, in which prospective

anticipation is gradually replaced with retrospective reassessment, can be generated with

a slider that animates the dynamic transformation in the value, identity, and relation of

temporal events. In such a view, temporal events expressed as a set of conditions, rather

than givens. The slider indicates a point of view, a perspective from which the experience

of temporality originates in an individual.

By breaking the relentlessly regular grid, the potential for graphing temporal

modeling as a complex system of events is greatly enhanced. The relational, and

co-dependent quality of temporal events finds its expression in these more sophisticated

models

Several fundamental principles can now guide these designs. These principles of

non-continuous, non-homogenous, and multi-directional temporality, as well as

the point of view parallax, refine the reductive crudeness of models linked to standard a

priori metrics of uni-directional, continuous, homogenous time. In this

refinement temporality is conceived according to the basic formulation mentioned above:

time as a function of x (temporality= time (x)). In these formulations, x is any of the

(theoretically infinite) variables that inflect the model (mood, events, influences,

events, constraints, etc.). Because temporality is an act of form-making (constructivist),

not an act of expressing pre-existing or a priori phenomena (realism), the sequence of

intellectual events in this formulation insists on temporality (and, likewise, spatiality

as the result of constitutive relations among temporal and spatial phenomena. The full

realization of this approach requires a multi-dimensional, complex, model of space and

time and imaginative realizations as graphical expression.

Space as Spatiality

The discussion of space corresponds exactly to that of time, and the distinctions between

the conception of space as an a priori given and that of space as relationally constituted

marks the same philosophical division of approaches as those that are used in charting or

understanding time and temporality. Likewise, spatiality is to be understood as space as a

function of x (spatiality= space

(x)).

[4]

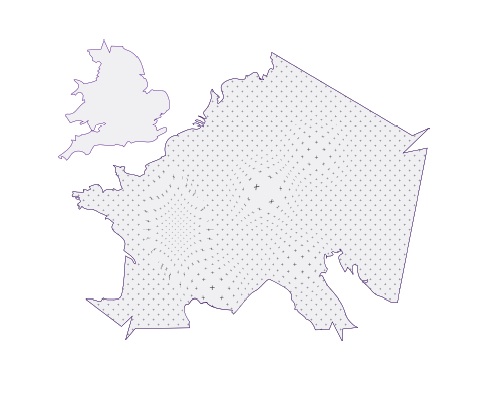

To give graphical expression to these ideas requires using non-standard metrics,

intuitive and subjective principles of design. They are meant as provocations to the

larger project of creating more systematic renderings of humanistic phenomena, introducing

basic transformations of the graphical fields we created for time lines into mapping and

GIS applications. Precedents for such renderings can be found–e.g. Francis Galton’s

rendering of space as a function of travel time. Galton’s problem, formulated in the mid

19th century, takes into account that most statistical phenomena are observer-dependent

and situated, and can’t be separated from the various dependencies that bear upon the

creation of data. Galton, in other words, recognized that in many circumstances, data were

capta. The statistical description of phenomena depend upon the observer’s circumstances.

A more recent demonstration of these principles is a map designed by Tom Carden. His

dynamic interface redraws the London Underground map as function of time of travel from

any selected station to any other station.

[5]

Subjective parameters are even more difficult to inscribe, since they cannot, by

definition, be based on simple consensual standards. We can easily understand these

distortions– space as a result of travel time. But how could we visualize the spatial

distortions introduced by variables such as fearfulness, anxiety, anticipation,

distraction, or dalliance and thus render space as spatiality, space as a factor of

x? Some variable is always in play in the experience of space as well as its

representation, so space is also always constructed according to a specific agenda and a

situated experience etc. While this is the common experience of the phenomenal world,

representations of spatiality have lagged behind, dominated by the navigational or

descriptive systems of standard mapping whose conventions are well known and recognized,

and which partake of and impose the dominant realist model.

In proposing a new model for humanities’ work, I am suggesting that the subjective

display of humanistic phenomena can be applied across the domains with which we are

concerned at at least four basic levels of interpretation or knowledge production.

- Modelling phenomenological experience in the making of

humanities (data as capta, primary modeling, the representation of temporal and

spatial experience);

- Modeling relations among humanities documents i.e. discourse fields (a different

metric is needed to understand dates on diplomatic documents in the spring of 1944

than one needed to constitute understanding of those dated to the same period of the

spring of 1950 etc.);

- Modeling the representations of temporality and spatiality that are in humanities

documents (narrative is the most obvious);

- Modeling the interpretation of any of the above (depicting or graphing the

performative quality of interpretation).

Let me describe a concrete

example and see how it can be understood across these four different models. Take the

first instance, the modeling of a phenomenon. Three people are waiting for a bus, how long

does it take? One is late for work and anxious, one is in desperate need of a bathroom,

and the other does not want to go to the afterschool program. How can the variations in

perception be expressed? Recent experiments on the way time is understood in relation to

different circumstances and tasks have made this experiential variable apparent to

psychologists. So, the initial graphical expression of the humanistic phenomenon requires

a variable metric, an elastic timeline, even a field that might fold or break under

extreme circumstances.

When we shift from modeling experience to find graphical expressions for the

representation of experience, the complexity of the problem increases. The modeling of

time in documents, in relation to the duration of the documents (time of telling) and the

experiences they recount (the time of the told) as well as the relations among these and

possible external temporal references, forms a subset of linguistic and narrative

analyses. The graphical forms to represent these are generally inadequate to the

complexity of the textual or visual (and/or filmic and audio) documents.

Modelling the temporal relations among documents about temporal experience (imagine

letters, emails, text messages, or diary entries from these various bus riders, only some

of which is date stamped), gives rise to yet further ambiguities and complexities. A

letter sent that was delayed, email re-routed, messages held in suspense on a server will

change the temporal effect. For instance, letters or emails arranging family events and

travels over the holidays contain many temporal values that are contingent on each other

and often in constant flux as plans are being made. The temporal sequence and the date

stamps are not one and the same, a temporal relation of the exchanges might include

messages that cross in mid-stream, and whose temporal sequence does not match the simple

alignment with dates on a line.

Plans change, travel times are altered, arrivals and departures re-arranged, moods shift,

frustrations intensify, disappointments or unexpected surprises arise in relation to the

sequence of events. An email recounting something that occurred “yesterday” in relation to

a date stamp might also contain more vaguely identified “earlier” and “before” statements

that put events into a relative sequence without explicitly identifying when these

occurred. As the telling unfolds, these relations may change in the writer’s expression

and perception, so that the textual description of a recollected event continues to shift

its place in the temporal order. Who was supposed to do what when and who was depending on

which order of events? By the time holiday travels and expectations are sorted out, each

family member has a very distinct view of what happened when and how the sequence of lived

events occurred and where. Was the bus station large or small, far or near to any other

spot in the itinerary, or located in a familiar landscape. How was the space experienced

as a function of time spent in it? These constructions of temporality and spatiality from

within documents, across documents or a discourse field, and of phenomena are all created

with time/space as functions of interpretation. The act of interpreting a series of

documents creates its own temporality, that of the production of a reading, that is not

the same as the telling or the told within the documents, but an independent phenomenon.

An interpretation has its own temporality ad spatiality.

We can construct a concrete example of spatiality that parallels this example of

temporality, and also depends on temporal models. For instance, imagine an open stretch of

beach, relatively unconstrained and unconstructed. When a sailing ship is washed up at a

certain point on the beach, not only that point, but the space around it, becomes

transformed. The presence of the wreck creates a huge impact, and the space almost

palpably bends, compresses, expands, and warps around it, with waves of resonance rippling

outward from that point.

Police barriers are set up and suddenly make that bit of beach into a highly

charged site. Additional fences create zones of potential transgression and prohibition,

lines in the literal sand that when crossed by graffiti artists and taggers, vandals and

looters, introduce a whole set of spatial relations governed by different rules and

expectations. The space of and around the shipwreck becomes a hot point, a zone, an arena

of complex spatial negotiations and marked coordinates, each differently charged depending

on the players and circumstances (law enforcement, owners, passersby, taggers at night, in

early morning, broad daylight etc.). Even more than the open, indeterminate space of the

beach, this spot becomes an area of shifting values and interpretation. Space, always

marked, has become explicitly so, and the spatial relations demarcate regions of authority

and behavior whose dimensions are not in strict correspondence to physical space. The same

amount of physical space half a mile down the beach has none (or few) of these dimensions.

Can we still locate the wreck on a Cartesian grid available through any GPS system? Of

course, the two approaches, constructivist and realist, don’t cancel each other out. But

they are not equivalent. The GPS standards locate the spot within those coordinates, but

say nothing about the constituted space as a phenomenon created by these many variables.

We have many adequate models for the first mode of visualization, but very few for the

constructivist approach grounded in an interpretative mode of experience.

Take another example, a map tracing a journey between London and Prague in the

1810s.

[6]; How does the space change dimensions to reflect hazard, delays,

dalliances, terrain changes, interruptions of war and political strife, danger, weather,

or illness? A legend or set of labels or markings could indicate these inflections of the

space simply by putting symbols on a map. That would be the registration of

subjective data on a conventional map. But mapping conventions don’t morph

the landscape to accommodate the effects of fear, anger, or violence. Now change the map,

distort its proportions so that it becomes a terrain shaped by fear, by obstacles, by

disruptions and confusions.

That is a subjective expression. The two approaches are radically

different. In the second instance, space is an effect of spatial relations, spatiality is

expressed as a factor of disturbance, and it might be expressed as a factor of many

variables occurring across a temporal extension (fear, anxiety, confusion, anger,

disorientation).

The challenge of representing large corpora of texts and immense archives also requires

attention, in part because the conventions of wayfinding and navigation that are part of

print media and its institutional structures are not yet reworked in a digital environment

meant to address the shifts in scale and experience brought on by new media. On top of the

challenge of representing repositories and their use, we can point to another challenge

–that of giving graphical expression to interpretations built on and out of documents, or

collections of documents. These present different challenges than the humanistic

interpretation of temporal, spatial, and informational phenomena, but depend upon the

basic recognition that subjective and co-dependent principles must govern their design.

The conventional graphical features of texts that inscribe interpretation include all of

the features of layout and format, typography, and design that organize and structure its

presentation on the page, screen, or other surface or medium. The features that inscribe

interpretation in archives are those that embody or express the imprint of the point of

view according to which the archive takes shape. These include classification systems,

nomenclature, hierarchies and categories of organization and ordering, systems of search

and access, information architecture, the format of storage and display, and any other

feature of the archive that is intrinsic to the forms of its expression. While all of

these are expressions of arguments, and thus interpretations, they do not show or model

interpretation on the fly as a constitutive act of reading, relating, connecting, and

sense making. In sum, these acts of interpretation make use of the format features of

graphical presentation as well as responding to and thus producing the “content” of these

artifacts. Some combination of user-centered but co-dependent systems analysis and

critical reading practices as performative acts would have to underpin such graphical

visualizations. But that is also work for another time.

Conclusion

My argument is a polemical call to humanists to think differently about the graphical

expressions in use in digital environments. A fundamental prejudice, I suggest, is

introduced by conceiving of data within any humanistic interpretative frame on a

conventional, uncritical, statistical basis. Few social scientists would proceed this way,

and the abandonment of interpretation in favor of a naïve approach to statistical

certainly skews the game from the outset in favor of a belief that data is

intrinsically quantitative — self-evident, value neutral, and

observer-independent. This belief excludes the possibilities of conceiving data as

qualitative, co-dependently constituted — in other words, of recognizing

that all data is capta.

Again, to reiterate, I am not suggesting that we simply introduce a quantitative analysis

of qualitative experience into our data sets. I am suggesting that we rethink the

foundation of the way data are conceived as capta by shifting

its terms from certainty to ambiguity and find graphical means of expressing

interpretative complexity. In some circumstances (the example of the bar chart given

earlier that was displaying information about gender, nations, and populations) ambiguity

merely requires a higher order level of complexity in the model, so that apparent

“certainties” are qualified by variables and nuances that can be specified in mathematical

terms. But the idea of capta as fundamentally co-dependent, constituted relationally,

between observer and observed phenomena, is fundamentally different from the concept of

data created as an observer-independent phenomena. That realization has to be at the heart

of humanistic approaches to the graphical display of interpretative phenomena, of

interpreted artifacts and the acts of interpretation themselves. Because interpretation is

performative, bringing objects into view through a reading or other act of intervention,

it forecloses the possibility that autonomous objects or phenomena exist within the

horizon of human experience. Phenomena of human experience are constituted as

interpretative acts.

The natural world and its cultural corollary exist, but the humanistic concept of

knowledge depends upon the interplay between a situated and circumstantial viewer and the

objects or experiences under examination and interpretation. That is the basic definition

of humanistic knowledge, and its graphical display must be specific to this definition in

its very foundational principles. The challenge is enormous, but essential, if the

humanistic worldview, grounded in the recognition of the interpretative nature of

knowledge, is to be part of the graphical expressions that come into play in the digital

environment. If we don’t engage with this challenge, we give the game away in advance,

ceding the territory of interpretation to the ruling authority of certainty established on

the false claims of observer-independent objectivity in the “visual display of

quantitative information.”

[7]

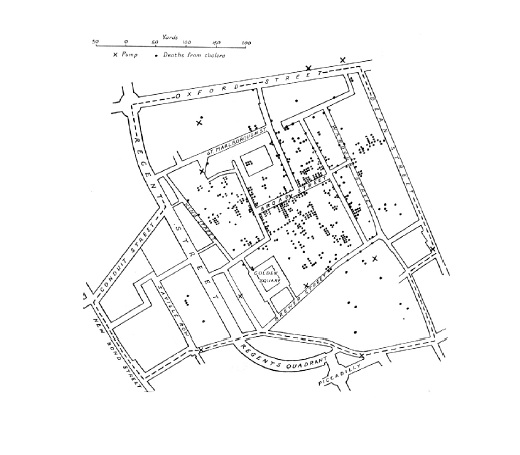

I’ll finish with one more concrete example of the shift from observer-independent realism

to co-dependent constructivism. Snow’s justly famous chart of deaths from cholera allowed

city officials to track the source of the epidemic to a single water pump.

The distribution of dots on the street map makes evident the role of the pump by

the way they cluster. A useful map, crucial to analysis, its clarity and succinctness

served an important purpose. It was sufficient to that purpose, adequate, but we could

revisit that map and use it to express other factors. Who are those dots? Each individual

had a profile, age, size, health, economic potential, family and social roles. In short,

each dot represents a life, and none of these are identical. Many demographic features

could be layered into this map to create a more complex statistical view of the epidemic.

That is neither subjective data nor a subjective display. But what if we take the rate of

deaths, their frequency, and chart that on a temporal axis inflected by increasing panic.

Then give a graphical expression to the shape of the terrain, that urban streetscape, as

it is redrawn to express the emotional landscape. Then imagine drawing this same

streetscape from the point of view of a mother of six young children, a recent widow, a

small child, or an elderly man whose son has just died.

These latter are all instances of the graphical expression of humanistic interpretation. They are as different from the

visual display of quantitative information as a close reading of a poem is from the chart

of an eye tracker following movements across a printed page. They are fundamentally

different in character and in their basic assumptions about the role of graphical

expression as an aspect of knowledge production. We have a very long way to go in creating

graphical expressions that serve humanistic interpretation, but I hope I have suggested

some of the premises on which this work might begin.

Works Cited

Anderson 2007

Anderson, Margo.

“Quantitative History”, The Sage Handbook of

Social Science Methodology, ed. William Outwaite and Stephen Turner, London:

Sage Publications, 2007, 246-63.

Anderson 2008

Anderson, Margo. “The Census, Audiences, and Publics”, Presidential Address, Social Science History 32:1, Spring 2008, 1-18.

Griethe & Schumann 2006

Griethe, Henning

and Heidrun Schumann. “Visualizing Uncertainty for Improved

Decision Making”, SimVis 2006, 143-156.

Jones et. al 2008

Jones, Josh, Remco Chang, Thomas

Butkiewicz and William Ribarsky. “Visualizing uncertainty

for geographical information in the terrorism database”,

SPIE Security

Symposium, 2008.

dvg.uncc.edu/publications/index.html

Knorr-Cetina & Amann 1990

Knorr-Centina,

Karin and Klaus Amann. “Image Dissection in Natural

Scientific Inquiry”, Science, Technology, and Human Values, 15: 1990, 259.

Latour 1986

Latour, Bruno. “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together”, Knowledge and Society, 6: 1986, 1-40.

Lochlann 2010

Lochlann, Jain.“ Morality Effect: Counting the Dead in the Cancer Trail”, Public Culture.

2010, 89-117.

Lynch & Woolgan 1988

Lynch, Michael, and

Steve Woolgar. “Introduction: Sociological Orientations to

Representational Practice in Science”, Human

Studies, 11: 1988, 99-116.

MacEachren et. al 2005

MacEachren, Alan M.,

Anthony Robinson, Susan Hopper, Steven Gardner, Robert Murray, Mark Gahegan and

Elisabeth Hetzler. “Visualizing Geospatial Information

Uncertainty: What We Know and What We Need to Know”,

Cartography and Geographic Information Science, Vol. 32, No. 3: 2005, 139-160.

Porter 1995

Porter, Ted. Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity, Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 1995.