Abstract

My research highlights the networks contemporary Black trans women create through the

production of digital media and in this article I make the emotional and

uncompensated labor of this community visible. I provide an added level of insight

into my research process as a way to mirror the access I was granted by these

collaborators. I use Digital Humanist Mark Sample’s concept of collaborative

construction to demonstrate my own efforts to enact a transformative

feminist process of writing and researching in the Digital Humanities (DH) while

highlighting the ways in which the communities I follow are doing the same in their

spheres of influence.

As I began to work on my book,

Misogynoir: Black Queer and Trans

Women Redefining Representations as Health Praxis, I prioritized

transparency. I used

my own

blog and the

Digital Humanities blog at Northeastern University to provide readers with

insights into the academic publishing process and my efforts to shape this process into

a more just experience for my research collaborators [

I'm Back 2014]. My

research highlights the networks contemporary Black trans women create through the

production of digital media and in this article I make the emotional and uncompensated

labor of this community visible. I provide an added level of insight into my research

process as a way to mirror the access I was granted by these collaborators. I use

Digital Humanist Mark Sample’s concept of

collaborative construction to

demonstrate my own efforts to enact a transformative feminist process of writing and

researching in the Digital Humanities (DH) while highlighting the ways in which the

communities I follow are doing the same in their spheres of influence.

The networks built through digital media production are significant attempts to redress

the lack of care that Black trans women receive from the health care community and

society. I argue that these processes of digital media production produce more than just

redefined representations but also connections that can be understood as a form of

health care praxis themselves. To reach these conclusions I have charted a new

methodology that incorporates theoretical perspectives from Black queer theory, digital

humanities, and feminist theory and transforms my relationship to the people producing

these digital representations.

Media and cultural studies scholars have long understood the epistemological and

pedagogical significance of popular media [

Hall 1993]; [

Jones 2003]; [

Jenks 1995]; [

Sperling 2011];

[

Macdonald1995]. Similarly, marginalized groups have often used media

production to challenge dominant scripts within mainstream outlets, and the rise of

digital platforms makes this task even easier. Black trans women’s use of Twitter, an

existing digital media platform, creates new and alternate representations as a practice

of health promotion, self-care, and wellness that challenge the ways they are depicted

in popular culture. I focus on a digital project by Black trans women that involves the

collaborative creation of images, links, and other digital media that trouble

problematic representations through a curation process that also works to enrich the

lives of those participating. I look at trans advocate Janet Mock’s twitter hashtag

#girlslikeus and discuss the many issues of trans women’s collective survival signaled

via the tweets marked by the tag.

I focus on Mock’s use of the hashtag because I sought and achieved her permission to

work on the project. I parse my process for achieving informed consent and how it

differs from the paternalism of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) process. I

acknowledge the negotiated terms under which this project is discussed to signal my own

queer feminist praxis in conducting this research. I build towards an understanding of

what I call digital alchemy as health praxis designed to create better

representations for those most marginalized in the Western biomedical industrial complex

through the implementation of networks of care beyond its boundaries.

Alchemy is the “science” of turning regular metals into gold. When I

discuss digital alchemy I am thinking of the ways that women of color,

Black women in particular, transform everyday digital media into valuable social justice

media magic that recodes failed dominant scripts. Digital alchemy shifts our collective

attention from biomedical interventions to the redefinition of representations that

provide another way of viewing Black queer and trans women. I argue that this process of

redefining representation challenges the normative standards of bodily representation

and health presented in popular and medical culture.

Connection through #girlslikeus

Black trans women negotiate unique threats to life and health as those multiply

marginalized by gender, race, sexuality, and the disproportionate amounts of violence

their communities face. On December 5, 2014, Deshawnda Sanchez, a Los Angeles area

Black trans woman, was killed while trying to escape her murderer. Her death was one

of 225 murders of trans women in 2014. The LGBTQ magazine

The

Advocate reported that in 2015, one trans woman has been murdered every

week and the majority of these deaths are of women of color [

Miami 2015]. These statistics do not reflect the frequent harassment, abuse, and harm that

trans women of color survive. The deadly violence that Black trans women negotiate is

often perpetrated by intimate partners, many of whom when asked claim they were

“duped” or “tricked” by their partners, and

then justifiably enraged to the point of murder [

Gay2015]. The popular

media trope of trans identity as a form of deception is iconized in the 1992 film

The Crying Game, a film that shows a man vomit when he realizes

that Dil, the Black woman he loves, is trans. Laverne Cox, a Black trans woman

portraying a trans woman on the Netflix original series

Orange

is the New Black, notwithstanding, the generally portrayal of trans women

and trans women of color in popular culture is one of hypersexual tricksters who

deserve to be victimized for deceiving cis men [

mattkane2012]. It is

again in the area of representation, in visual assessment, that trans women of color

are judged and then responsible for the resulting violence it elicits from the people

closest to them [

Lee 2014]; [

Lee 2008]; [

Steinberg 2005].

These acts of violence also coincide with increasing visibility and advocacy by trans

women of color, particularly through digital media outlets and in online media. In

2012, Mock was moved to become a more outspoken trans activist because of the rise in

the number of murders and suicides of queer and trans youth. She has used her

platform as a former web editor for

Marie Claire as well

as digital tools like videos and hashtags to reach out to other trans women in

society. In explaining the origin of her hashtag #girlslikeus, Mock describes her

support of Jenna Talackova, a contestant disqualified for the Miss Universe Pageant

for in the words of the pageant officiates, “not being a natural born female”

[

Miss Universe 2014]. Mock’s desire to help Talackova achieve her dream

lead to the creation of the hashtag. On her personal blog Mock wrote,

So I shared Jenna’s petition on Twitter, and said: Please sign & share this

women's rights petition in support of transgender beauty queen Jenna Talackova

& #girlslikeus:

ow.ly/9TYc6

27 Mar

12 And that was the online birth of #girlslikeus. I didn’t think it over,

it wasn’t a major push, but #girlslikeus felt right. Remarkably a few more women —

some well-known, others not — shared the petition and began sharing their stories

of being deemed un-real, being called out, working it, fighting for what’s right,

wanting to transition, dreaming to do this, accomplishing that... #girlslikeus

soon grew beyond me... my dream came true: #girlslikeus was used on its own

without my @janetmock handle in it. It had a life of its own [Why I Started].

Other trans women have embraced the tag, including Laverne Cox; they use it to

discuss everything from the desire to transition and the violence of being outed in

unsafe situations as well as the banality of everyday living and dreams of job

success.

Computational Scientist Alan Mislove created a database that collects a random ten

percent of all tweets tweeted since Twitter began. As scholars in sociology and DH

have noted, a ten percent sample of such a large database can provide statically

significant information about the representative population [

Mislove 2011]; [

Gerlitz 2013]; [

Twitter Usage]; [

Bruns 2013]. I examined all

publically accessible tweets using #girlslikeus between Mock’s first uses in March

2012 until October 2014. With the help of computer science graduate student Devin

Gaffney, we created a script that gathered all instances of the hashtag within this

database. With over 11,000 tweets stored that used the hashtag I could begin to

assess significance. I used Voyant, a web-based textual analysis tool that can

generate word visualizations and measure the frequency and occurrence of words in a

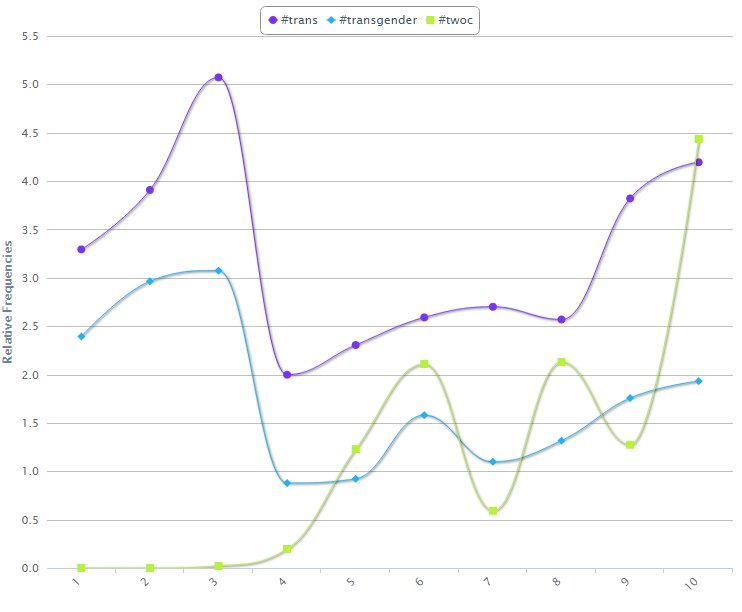

corpus, to mine the texts of the collected tweets. The most popular hashtags used

with the hashtag #girlslikeus were other words of identity affirmation, including

#trans and #transgender, #twoc (trans women of color).

These hashtags fluctuated in use over this two year period, with #transgender having

fallen below its initial prevalence and #twoc significantly increasing.

Words related to representation were very popular, ultimately marking the content of

nearly every tenth tweet. Variations of the words picture,

selfie, as well as types of media and news outlets drove this

significance, often pointing to pictures and links that affirmed trans women in ways

that counter their portrayal in mainstream media. News outlets might provide a mug

shot, or a picture of a trans woman offered by a family member that illustrates her

appearance at an earlier point of transition. By being able to control their own

images, trans women are able to subvert societal impulses to lock them into

representation that recalls their assigned sex at birth. These acts of digital

alchemy affirm the twitter user and the network built via the hashtag.

For example, Janet Mock in May of 2013 attended the celebration of Laverne Cox’s Time

magazine cover, captioning their photo together, “Celebrating Laverne Cox’s time cover tonight in NYC.

Sisterhood in action! #girlslikeus [

Laverne 2015].”

Though celebrating a friend’s appearance on the cover of Time magazine is not

something that we can necessarily relate to, celebrating friends and their success

through posting a picture on Twitter is very common. I won’t provide visual referents

of the types of images that these daily life photos subvert, but think about the

trauma and violence that befalls Dil in

The Crying Game

or the way trans women are often made to account for their genitalia in popular

culture by journalists in order to be invited guests [

Laverne 2015].

Tweets like this one, which show the daily and collective joys that trans women

experience, challenge the proliferation of media representations that focus solely on

their anatomy and victimization. Despite this tendency to over represent trans women

in a salacious way, mainstream media continues to under report and misgender

transwomen in the news [

Michaelson 2012].

Transforming Methodology Through Collaborative Consent

Given the frequent attacks on trans women, particularly trans women of color, I

wanted to be sure that my scholarly inquiries about the hashtag were welcome and did

not bring undue negative attention to the community. I reached out to Mock via

Twitter to see if she was interested in my researching the tag. I told her I was

interested in how it has been used and what sorts of actions have developed through

its use. She said she would be excited for me to work on the project. I also asked

her what sort of information would be most useful to her to know about the hashtag.

She was specifically interested in the most popular retweets and users along with

gathering a sense of where the hashtag has shown up in mainstream media.

Though Mock welcomed my research on the hashtag, I wanted to give her the opportunity

to say no to the project. My own interest was not enough justification for pursuing

this type of potentially risky research that could expose an already vulnerable

community to more vitriol and negative visibility. Trans women of color are not

understood as one of the vulnerable communities identified by the Institutional

Review Board that assesses the potential harms of academic research on those

researched. The IRB recognizes prisoners, people with diminished capacity, women,

particularly in their capacity as potential child bearers, and minors themselves as

populations that could be unduly harmed by human subjects research. Trans women of

color are represented within these populations yet are not recognized as their own

contingent in need of more nuanced ethical study. I don’t wish to see trans women of

color represented in this list of vulnerable populations; however, I do think that

the IRB's mandate to cause no undue harm to research participants requires

researchers to think more carefully about emergent communities where people’s very

humanity is being questioned in society writ large.

The intentions of the IRB are quite noble and necessary. IRBs are charged with

ensuring that human subjects research conducted at institutions that receive federal

resources is ethical and does not cause harm to participant [

Kim 2012].

In response to human rights abuses of marginalized groups within the US, the IRB was

established to ensure that human subjects research did not cause undo harm to those

participating in studies [

Williams 1984]; [

Bradley 2007].

This function of the IRB tends to result in a paternalistic orientation towards

research subjects, predicated on benevolence and the idea that “many prospective subjects are vulnerable to a range of

decisional defects or impairments that render them unable to protect their own

interests, and thus we are right not to rely exclusively on informed

consent”

[

Miller 2007]. The IRB evaluates the proposed research to ensure that

investigators have thought through the potential impacts of the research on the

people being researched, assuming that there are potential risks that the average

research subject might not be able to detect if it weren’t brought to their

attention. This paternalism may be a valid position for the researcher to take given

the type of research to be conducted but in the digital landscape, a more nuanced and

fluid understanding of the way power flows between researcher and researched is

needed.

Social media users are not the traditionally infantilized research subjects that the

IRB assumes. As people who are actively engaged in the ongoing generation of their

digital content, social media users require a level of forethought that extends

beyond the purview of the IRB. While IRB review might be able to forestall some of

the harms that are involved in academic research, issues of consent beyond an initial

yes to participate in a research project or plans to address issues that may not be

anticipated by the IRB are obfuscated.

Previous studies have attempted to address IRB paternalism and its impact on research

subjects in several ways. In the social sciences, there have been efforts to shift

research from a top down orientation to one that is side to side or bottom up [

Sabatier 1986]; [

Erickson 2006]; [

Plesner 2011]. These methodologies attempt to undo the power imbalance

by shifting people’s relationships to power. Participation observation or becoming an

observing participant are other ways that this conversation is framed, relying on the

researchers shifting location into the research as the mechanism which disrupts the

traditional flow of power [

Maguire1987]; [

McCall 1969];

[

Weasel 2011]. My experience in trying to shift my relationship to

power involved collaboration even before developing my research methodology.

By speaking with Mock, before even designing my research plan, I ensured that the

findings are useful to her as the creator of the hashtag. In addition to speaking

with Mock directly, I spoke with my online community of friends and activists to

create an advisory panel. I reached out to Black women and queer thought leaders

within the arenas of Twitter and Tumblr, which included a diverse group of activist,

artists, and academics, who have created some of the most popular hashtags related to

social justice issues. Twitter and Tumblr users like Sydette Harry and Jamie Nesbitt

Golden have been central to the creation and popularity of many social justice

related hashtags. Many of them have direct experience with journalists and scholars

using their social media posts without their consent. These incidents range from

annoying to outright dangerous. Many amongst this group of twelve have had their work

stolen by journalists, interpreted by scholars all without attempting to contact

them. They have experienced rape and death threats for simply voicing their opinions

online. Given these histories, I did not want to repeat a pattern of beginning work

without asking for permission first nor giving them the opportunity to ask their own

research questions.

I plan to ask within the networks using #girlslikeus what users think about the

project and what questions they want answered about how it moves through cyberspace

and the world. Even though tweets are understood as public, I err on the side of

privacy and anonymity for Twitter users of the hashtag. I will not use the handles of

users without first attempting to contact them. By allowing Twitter users to shape

the project and their participation at multiple points, I create a more flexible

process, one that is dynamic and shifting. But the collaboration doesn’t end

there.

My experience with issues of ongoing consent suggests that the way we do digital

humanities needs to shift. Digital Humanists interested in conducting research that

is ethical and feminist must go beyond the simple politics of citation, as citation

itself may be the thing that creates the harm to the community. As noted in The

#TwitterEthics Manifesto, “both

academics and journalists should ask each individual user on Twitter for consent.

They should explain the context and the usage of their tweets”

[

Twitterethics2014]. This allows a Twitter user to prepare for a

potential onslaught or simply say no. Consent is a form of collaboration, a

collaborative process which means that a

no may come later in the course

of the collaboration. Similarly, the process of doing this research necessitates an

ongoing commitment to understanding dynamics that emerge through engagement in the

medium. To that end, the advisory panel proved to be more dynamic than even I could

have anticipated.

Collaborative Construction: What transforms in the doing

I sent the potential members of my advisory committee an email asking if they’d like

to participate. Those who agreed were invited to join a listserv where I post

questions and solicit help as needed. While this group was initially created to

ensure that my work was ethical and useful, it has already been repurposed for needs

I could not anticipate. One member of the group is an internationally renowned

journalist. She queried the collaborators, asking for their thoughts on a story she

was writing about the ways that the media has represented Black people, particularly

Black women in coverage of the Ebola outbreak. Many in the group responded to her

request, providing important quotes that shaped her article in really helpful ways.

When I envisioned the group, I imagined what I could do for them and what they could

do for me. Even in creating a collaborative space it didn’t occur to me that there

might be things that we could collectively do for another member of the circle. I

knew what I wanted from the group and assumed that I could anticipate the group’s

needs from me. However, this emergent need and purpose for the group was possible

through the creation of the network itself. Even before I could use the network in

the way I envisioned, my collaborators were able to leverage it to meet their own

needs.

Stressing a non-hierarchal circular collaboration is what helped make this possible.

I had transformed the traditional top down approach of my research but I had only

imagined a relationship that was side by side, a horizontal relationship with me on

one side and my collaborators on the other. This moment allowed for the realization

that we had co-created a three dimensional space with multiple directions of flow.

What I appreciate about the language of collaborators as opposed to

research subjects is that it provides the potential for multiple

levels of relationship between those participating in the research; the structure is

dynamic.

Those of us who participated in interviews for the journal article were not

compensated, and there were a few minor errors in the article that I believe in

another context would have been hurtful. However, the initial transparent ask, the

openness to feedback, the knowledge that we were all participating in a process that

extends beyond the published article and even my book, created a level of trust that

allowed for forgiveness and correction among peers. Many of these collaborators have

experienced the unsolicited appropriation of their words by people they did not know.

By developing a new community, albeit a short lived one, the power differentials

among the members are mitigated. While I still maintain epistemic privilege as the

gatherer and convener of this circle, I am interested in using that privilege for the

collective good [

On 1993].

Because academic books make very little money, I endeavored to find meaningful ways

to compensate this group for their work and time. This includes using university

research money to help convene gatherings for existing digital networks that may have

trouble connecting in another capacity. Creating a fund from honoraria received in

relationship to the work, in addition to coauthoring articles with interested

collaborators. are a few of the ways I am exploring transforming my relationship to

my collaborators. I’ve been able to leverage my position within academic communities

to write grants that include budget opportunities for these collaborators and more.

As the project continues I am creating more opportunities that challenge the ways

that researchers have traditionally compensated and shared in the benefits that come

from doing research.

One of the important aspects of DH work is the emphasis on collaboration. Scholars in

the humanities are still primarily rewarded for single author texts. Tenure and

promotion committees regard books and articles that have one author more favorably

than mutli-authored texts. One of the ways that DH is creating a different

methodological practice is by supporting connection through collaboration across

multiple aspects of digital projects. Digital Humanist Mark Sample discusses this

idea in relationship to student work through his concept

collaborative

construction. He writes,

[B]y collaborative construction, I mean a collective effort to build something

new, in which each student’s contribution works in dialogue with every other

student’s contribution. A key point of collaborative construction is that the

students are not merely making something for themselves or for their professor.

They are making it for each other, and, in the best scenarios, for the outside

world [Sample 2012].

I adapt this idea of collaborative construction such that it has import outside the

realm of the classroom; it is critical to the way that I shape my research project.

Consequently, a transformation of the goals of my academic work was necessary, as

well as my relationship to the usually distinct categories of research subject,

researcher, and audience.

My work has multiple audiences. There are scholars in fields like women’s, gender,

and sexuality studies, ethnic studies, and digital humanities who might be interested

understanding the networks contemporary Black trans women create through the

production of digital media. However I am interested in creating a book that also and

perhaps most importantly, is useful to the communities on which my examples draw.

More than just the world outside the academy, I want to create a resource for the

communities with whom I am collaborating on the research. This practice involves a

more intentional form of collaboration than I have attempted before.

I am creating a new way of practicing the relationships I am developing through my

the advisory panel, transforming a researcher/researched relationship into one of

collaboration, thereby shifting out of the position of researcher into a more equal

role. This process also includes developing new models of expressing the value of

everyone’s contributions. For me, the process is the product, meaning that the

process itself is productive, creative, and transformative of the conditions we are

seeking to understand through the research [

Twitterethics2014]. We are

building collaboratively in ways that build community and shift existing dynamics. We

are actively shaping the project of collaborating through our collective

participation so that an end product, while potentially very useful, is not the only

thing created by this collaborative investigation.

The example of trans women of color’s digital activism demonstrate the power of

digital media to redefine representations of marginalized groups and their ability to

impact a white supremacist, heterosexist, and trans misogynist media culture without

that being their primary goal. The practices of reclaiming the screens of our

computers and phones with content is not simply one of creating new representations

but is a practice of self-preservation and health promotion through the networks of

digital media. While often celebrated for the rehabilitated images, this media is not

often interrogated as processes that support the development of community and

individual health strategies. Trans women of color aren’t simply naming the violence

they experience but are building networks of support and recognition for their work

that helps them have safer environments in which to live.

I understand trans women of color’s production of media as an act of

self-preservation and one of health praxis that is not centered on appeals to a

majority audience. The creation of media by minoritarian subjects about themselves

and for themselves can be a liberatory act. These acts of image redefinition actually

engender different outcomes for marginalized groups and the processes by which they

are created build networks of resilience that far outlives the relevant content.

Black women and queer and trans folks reconstruct representations through

digital alchemy.

#Girlslikeus rejects the assimilationist invisibility of another potential hashtag

like #imagirltoo, in favor of a declaration that makes trans women the undeniable

center of their own project, where they are their own referents, not cis women.

#Girlslikeus signals a conversation that is for, by, and about trans women and not

their proximity to another group of relative power. #Girlslikeus exemplifies the

magic of digital alchemy through this practice of shifting from margin to center

utilizing established mediums to create literally transformative realities.

The added benefit of creating this community online is that it is visible to those

outside the identity and does the work of humanizing inadvertently and without

draining energy from the more important work of supporting each other. Digital media

is creating and supporting a network of connection among communities that have

traditionally had trouble finding each other let alone reaching a larger audience. By

doing the work of community building online, groups are leveraging both visibility

and education at once. Trans women of color are telling their own stories but in the

process are forcing more recognition for their identities in mainstream publics.

Putting Process into Practice

As a member of the Allied Media Projects community, I have been shaped by the

organization’s values and principles. Allied Media Projects mission is to “cultivate media strategies for a more just and creative

world” (n.d.). The annual Allied Media Conference that highlights work from

activists, artists, and organizers in service of this mission, highlights the words

create, connect, and transform in their

advertising for the event. I find these verbs particularly useful in marking the

different components of this project that trouble more traditional methodologies in

my fields of study. I see these three components of connection,

creation, and transformation as the template for the

types of questions we should be asking about our digital research. I have identified

the questions these verbs raise for me in my own research which may be a good

starting place for others who are interested in the same.

Connect

- Who are your collaborators?

- What community is your research accountable to beyond your academic

community?

- How will you demonstrate your desire to be accountable to them?

- Are there people you can talk to about the impact of your research beyond

the IRB?

- How does everyone benefit from the research?

- What questions does the community want answered?

- Can people be compensated in ways that honor their time and

skills?

Create

- What tools and or methods encourage multidirectional collaboration?

- What mechanism of accountability can you create?

- Are there ways that collaborators can use the research process to their

own ends?

- What kind of process can you create for your research?

- Is there room for collaborators to give and rescind consent at different

times during the research process?

- Does the pace of the project meet your needs and your collaborators

needs?

Transform

- How will you take care of yourself in the research process?

- What do you and your collaborators need to stay sustained while

conducting the research?

- What happens after the research product is complete?

- How will you be transformed?

- Will the research strengthen your connection to your

collaborators?

- Did you and your collaborators come to new understandings?

I offer these questions as a starting place for conducting digital research within a

feminist ethical frame. I am reminded of Octavia Butler’s aphorism “all you touch you change; all you change,

changes you”

[

Melzer2002]. With this tenant in mind, I think that the important

take away here is that the very process of conduct research creates shifts in the

landscape. These shifts have incredible potential to be both helpful and harmful,

depending on how you frame your project and interactions with your collaborators.

The Research Justice collective at the AMC frames their work with the question “is this just research or just

research?” I want my research to be just and I had to set my

parameters for what that means. I realized that I can’t answer these questions by

myself. I am close but not embedded in these digital networks I study. I’ve tried to

shape the process of my investigation in a way that honors the principles set out in

the Allied Media Project mission. My project is collaborative and builds connection;

it’s creative in that I’m generating something useful in the media; and it’s

transformative in that my collaborators and I will be changed by the process of doing

the research.

Works Cited

Bradley 2007 Bradley, Matt. 2007. “Silenced for Their Own Protection: How the IRB Marginalizes Those It

Feigns to Protect.”

ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical

Geographies 6 (3): 339–49.

Bruns 2013 Bruns, Axel, and Stefan Stieglitz. 2013.

“Towards More Systematic Twitter Analysis: Metrics for

Tweeting Activities.”

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16

(2): 91–108. doi:10.1080/13645579.2012.756095.

Erickson 2006 Erickson, Frederick. 2006. “Studying Side by Side: Collaborative Action Ethnography in

Educational Research.”

Innovations in Educational Ethnography: Theory, Methods, and

Results, 235–58.

Hall 1993 Hall, Stuart. 1993. What Is This

“Black” in Black Popular Culture?

Social Justice, 104–14.

Jenks 1995 Jenks, Chris. 1995. Visual Culture. Edited by Chris Jenks. London; New York:

Routledge.

Jones 2003 Jones, Amelia The

Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, Edited by Amelia Jones. London ; New

York: Routledge.

Kim 2012 Kim, Won Oak. 2012. “Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Ethical Issues in Clinical Research.”

Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 62 (1): 3–12.

doi:10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.3.

Macdonald1995 Macdonald, Myra. 1995. Representing Women: Myths of Femininity in the Popular

Media. E. Arnold London and New York.

McCall 1969 McCall, George J., and Jerry Laird

Simmons. 1969. Issues in Participant Observation: A Text and

Reader. Vol. 7027. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Melzer2002 Melzer, Patricia. 2002. “‘All That You Touch You Change:’ Utopian Desire and the Concept

of Change in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the

Talents.”

Femspec 3 (2): 31.

Miller 2007 Miller, Franklin G., and Alan Wertheimer.

2007. “Facing up to Paternalism in Research Ethics.”

Hastings Center Report 37 (3): 24–34.

doi:10.1353/hcr.2007.0044.

Mislove 2011 Mislove, Alan, Sune Lehmann, Yong-Yeol

Ahn, Jukka-Pekka Onnela, and J. Niels Rosenquist. 2011. “Understanding the Demographics of Twitter Users.”

ICWSM 11: 5th.

On 1993 On, Bat-Ami Bar, and Bat Ami. 1993. “Marginality and Epistemic Privilege.”

Feminist Epistemologies 83: 199.

Plesner 2011 Plesner, Ursula. 2011. “Studying Sideways: Displacing the Problem of Power in Research

Interviews With Sociologists and Journalists.”

Qualitative Inquiry 17 (6): 471–82.

doi:10.1177/1077800411409871.

Sabatier 1986 Sabatier, Paul A. 1986. “Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches to Implementation Research: A

Critical Analysis and Suggested Synthesis.”

Journal of Public Policy 6 (01): 21–48.

Sperling 2011 Sperling, Joy. 2011. “Reframing the Study of American Visual Culture: From National

Studies to Transnational Digital Networks.”

The Journal of American Culture 34 (1): 26–35.

doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2011.00761.x.

Steinberg 2005 Steinberg, Victoria L. 2005. “A Heat of Passion Offense: Emotion and Bias in ‘Trans

Panic’ Mitigation Claims: Hiding from Humanity.” By Martha C.

Nussbaum. BC Third World LJ 25: 499–499.

Williams 1984 Williams, Peter C. 1984. “Success in Spite of Failure: Why IRBs Falter in Reviewing Risks and

Benefits.”

IRB: Ethics and Human Research 6 (3): 1–4.

doi:10.2307/3563870.