Abstract

The close study of literary texts has a long and illustrious history. But the

popularity of textual analysis has waned in recent decades, just at the time that

widely available electronic texts were making traditional analytic tools easier to

apply and encouraging the development of innovative computer-assisted tools. Without

claiming any simple causal relationship, I argue that the marginalization of textual

analysis and other text-centered approaches owes something to the dominance of

Chomskyan linguistics and the popularity of high theory. Certainly both an

introspective, sentence-oriented, formalist linguistic approach and literary theories

deeply influenced by ideas about the sign's instability and the tendency of texts to

disintegrate under critical pressure minimize the importance of the text. Using

examples from Noam Chomsky, Jerome McGann, and Stanley Fish, I argue for a return to

the text, specifically the electronic, computable text, to see what corpora,

text-analysis, statistical stylistics, and authorship attribution can reveal about

meanings and style. The recent resurgence of interest in scholarly editions, corpora,

text- analysis, stylistics, and authorship suggest that the electronic text may

finally reach its full potential.

Introduction

Unfortunately for the history of digital humanities, the advent of widely available

electronic texts coincided with the Chomsky years in linguistics and the theory years

in literary studies. Although these orthodoxies rest on very different theoretical

underpinnings, they both tend to deny the legitimacy of text-analysis and stylistics.

They de-emphasize the close study of texts and cast doubt on its significance and

centrality.

Chomsky’s mentalist approach, which has dominated American linguistics for more than

forty years, locates its site of interest in the mind and treats texts and other

stretches of naturally occurring language almost as irrelevant excrescences on the

body of the innate language organ. It emphasizes the formal nature of grammar,

downplays semantics, focuses on competence/deep structure rather than textual domain

of performance/surface structure, ignores literature, and restricts itself to the

scope of the sentence.

Much high theory is deeply influenced by ideas about the instability of the sign and

the tendency of texts to disintegrate under critical pressure, ideas most closely

associated with the late Jacques Derrida. Theory has had almost nothing to say about

Chomsky, focusing instead on Saussure, a linguist whose ideas are more congenial, at

least in the sense that they discuss the process of signification at length. Jerome

McGann, for example, champions the game-like, “fundamentally subjective character of . . . criticism”

[

McGann 2004, 50–1] and asks “What if the question isn’t ‘

how could he [the critic] take himself or his ideas seriously’

but ‘why

should he take himself or his ideas seriously’?”

[

McGann 2004, 50]. Stanley Fish emphasizes the reader’s role,

attacking the idea that texts have meaning at all–arguing that the only links that

exist between the text and its interpretation are those that are “fashioned in response to the demands of the reading

experience”

[

Fish 1980, 64]. Critical approaches like these and a more general

distrust of the sign/signified link within literary theory helped to produce a

climate inhospitable to text-analysis and stylistics.

It is not necessary to insist on any direct causal relationship between the hegemony

of Chomskyan linguistics and high theory and the marginalization of textual analysis

and other text-centered approaches, but, whatever their other merits, these two

influential trends have certainly helped to keep the tremendous potential of

electronic texts for literary study from being realized. Recently, however, there

have been signs of a resurgence of interest in scholarly editions, corpora,

text-analysis, stylistics, and authorship that suggest that the electronic text may

finally reach its full potential. Because the point I want to make is such a basic

one, I will present only a couple of very simple ways of returning to the text,

merely mentioning some more sophisticated methods in my conclusion. The nature of the

methodology is less important than the reestablishment of the text as the central

focus of inquiry, as one of the most important objects of study.

Chomsky, Innateness, and the Irrelevant Text

Let us begin with Chomsky, and one of the most characteristic and important

principles of his theory: the innateness of linguistic ability. If it is not

immediately apparent that a belief that human language is largely the result of a set

of innate mechanisms necessarily devalues texts, an examination of one of the most

central of Chomsky’s arguments for innateness quickly shows why this is so. In a move

that harkens back to Plato’s argument for innate ideas, Chomsky argues that language

learning would be impossible without a rich, specifically linguistic innate mental

structure. The facts that a native speaker knows about the language, he argues, are

too complex, too subtle, too regular, and too unpredictable to have been learned from

the language to which the child has been exposed. Because the speaker manifestly

knows them, there must be an innate language component that allows the speaker to

“acquire” language (not “learn” it) with extreme rapidity, without

explicit instruction, and on the basis of evidence that is inadequate and often

corrupt.

This is not the place to examine all of Chomsky’s arguments (for a thorough and

careful critique of the innateness hypothesis and various arguments for it, see [

Sampson 2005]). For my purposes, however, I will focus on the last

argument, that the evidence to which the child is exposed is inadequate and corrupt.

Although it is increasingly clear that the language children are exposed to is less

corrupt than Chomsky supposed (why he supposed it rather than examining it is another

aspect of the devaluation of text), but the more important question for the history

and future of the study of texts is whether his argument from lack of evidence is

persuasive, whether it is true that speakers know things for which they have no

relevant experience. Another way of framing his argument is to say that the

“texts” on the basis of which a child comes to know a language are faulty,

incomplete, and insufficient. Given that, why study them?

One classic and often-repeated kind of evidence for innateness comes from question

formation in English. How can a child determine the correct form of the question

version of “The man is tall”

[

Chomsky 1975, 31]? The simplest rule that the child might

entertain is that the first verb moves to the front, which correctly gives “Is the

man tall?” But in “The man who is tall is in the room,” this simple rule

gives the wrong question form: “*Is the man who tall is in the room?” (Here, as

is usual in linguistic discussions, the asterisk marks an ungrammatical form.) The

correct rule requires that the child analyze the grammatical structure of the

sentence and apply a more accurate but more complicated rule: move the first verb

after the first noun phrase of the main sentence to the front [

Chomsky 1975, 31–2]. The crucial argument for innateness is that,

as Chomsky puts it, “A person may go

through a considerable part of his life without ever facing relevant evidence, but

he will have no hesitation in using the structure-dependent rule, even if all of

his experience is consistent with” the simpler rule [

Chomsky 1975, 32]. Because all speakers of English arrive at a rule

for which they often have no relevant evidence, knowledge of grammatical principles

must be innate.

In his wonderful book,

The “Language Instinct”

Debate, Geoffrey Sampson uses textual evidence from corpora very

effectively to counter this classic argument for innateness. He presents “The subjects who have acted as controls will

be paid” as his example of a sentence for which the simple rule gives the

incorrect result. He notes that Blake’s “Did he who made the lamb make thee?” is an example of counter-evidence

that most school children will be exposed to, and then finds that 12% of all yes/no

questions in a 40 million word

Wall Street Journal

corpus from 1987-89 are of a form that would contradict the potentially wrong rule

[

Sampson 2005, 46–47]. There is thus no reason to think that

speakers lack the relevant evidence against the simple form of the question rule, and

one of Chomsky’s central arguments for innateness loses much of its force. What

Sampson’s example makes clear is that Chomsky’s reliance on intuition and his

rejection of textual evidence leads him to base a central premise of his innateness

hypothesis on the non-existence of sentence types that actually occur fairly

frequently.

In fairness, when Chomsky first presented this argument, there were no huge corpora

for him to examine, and some of the subtle grammatical facts upon which his arguments

depend are so infrequent that it would have been quixotic to have searched for

examples. Yet the grounds for Chomsky’s rejection of corpora and of the evidence of

texts are more theoretical than practical, so that the subsequent availability of

huge corpora has had almost no impact on the Chomskyan tradition.

A second claim for an innate grammatical principle that can be contested using

electronic corpora involves the following sentences:

(1)

- a. John was (too) clever to catch.

- b. John was (too) clever to be caught.

- c. John was (too) easy to catch.

- d. John was (too) easy to be caught.

[Chomsky 2000, 168]

Chomsky argues that an innate Faculty of Language (FL) that is “common to the species, assuming states that vary in limited

ways with experience”

[

Chomsky 2000, 168] is required to explain how a person can

produce sentences like (1a-d), and understand some surprising features of their

meaning. Chomsky’s important insights about such sentences involve agency and the

question of what the adjective modifies. As he suggests, with “too,” they don’t

catch John in (1a-b) and “clever” modifies John. It is unclear whether or not

they catch John in (1c-d) (“John was easy for them to catch, so they didn’t

bother.”), but the catching is “easy,” not John. We may all agree that

these are interesting observations, especially because the sentences seem so similar

in structure, but not everyone agrees that (1d) is deviant, as his proposed innate

principle requires. Phrases like “easy to be caught” are so rare that

Wall Street Journal corpus and even the 100 million word

British National Corpus (BNC) are too small to provide sufficient examples for

analysis, though I did find the following tantalizing parallel to the deviant form in

1d in Mark Davies new 100+ million word

Time Magazine corpus

(2007): “The Clinton are just not easy to be

caught by a pumpkin head”

[

Trillin 1998]. Chomsky’s argument is not tied to any particular verb, however, so that we

can also consider the exactly parallel sentence with a more common verb: “John was

easy to find/easy to be found.” Chomsky’s argument obviously entails the

deviance of the passive version of this sentence, but counterexamples to his views

are too easy to be found in real sentences for them to be taken seriously. My

preceding sentence violates his claim, as do thousands of sentences that a Google

search for “easy to be found” (7/16/06) returns.

Although Google is neither a good nor a representative corpus, my interest here is

in naturally occurring texts. Thus it seems reasonable to allow Google’s enormous

body of texts to act as a corpus, so long as its limitations are acknowledged.

Chomsky’s argument, remember, is that “John

is easy to be caught” violates an innate principle of grammar, so that the

presence of large numbers of examples of this construction, even in a relatively poor

corpus, should count as evidence against his theory.

Chomsky might reject many of the Google hits as modern, casual examples, ones in

which “performance” might not match “competence.” The search also uncovers

many examples from standard edited English, however. The fact that these were

discovered using Google is clearly unimportant, and the relatively long list below

makes its own point (each was accessed at the listed URL on July 16, 2006):

For nothing is more easy to be found, then

be barking Scyllas, ravening Celenos, and Loestrygonians devourers of people,

and such like great, and incredible monsters.

[More 1914]

And the reason why the MACEDONIANS kept so

easily dominion over them was owing to other causes easy to be found in the

historians . . . .

[Hume 1748]

But, he himself was less easy to be

found; for, he had led a wandering life, and settled people had lost sight of

him.

[Dickens 1858]

Also many precedents of ill success and

lamentable miseries befallen others in the like designs were easy to be found,

and not forgotten to be alleged.

[Bradford 1647]

It has been said, that he used

unprecedented and improper instruments of correction. Of this accusation the

meaning is not very easy to be found.

[Boswell 1791]

eaþ-fynde; adj. Easy to be found;

facilis inventu:-- Ðá wæs eáþfynde.

[Bosworth and Toller 1898]

Then a trail on land is not easy to be

found in the dark.

[Cooper 1840]

May they bring hither hundreds,

thousands for our men: may they bring hidden stores to light, and make wealth

easy to be found.

[Griffith 1896]

One of them, she who drank out of the

red-head's cup, so fair, and with such a pleasant slim grace, that her like

were not easy to be found.

[Morris 1895]

Mark then the goal, 'tis easy to be found;

/ Yon aged trunk, a cubit from the ground.

[Pope 1715-20]

Besides, there grows a flower in marshy

ground, / Its name amellus, easy to be found.

[Addison 1694]

Avoid the rocks on Britain's angry shore.

/ They lie, alas! too easy to be found; / For thee alone they lie the island

round.

[Swift 1726]

“Hang on a minute,” I hear the reader say. “You seem to be telling us

that this man who is by common consent the world’s leading living

intellectual, according to Cambridge University a second Plato, is basing

his radical reassessment of human nature largely on the claim that a certain

thing never happens; he tells us that it strains his credulity to think that

it might happen, but he has never looked, and people who have looked find

that it happens a lot.”

Yes, that’s about the size of it. Funny old world, isn’t it! [Sampson 2005, 47]

One of Chomsky’s standard arguments that might seem to save his innate principle

from such textual evidence is that there is no necessary connection between our

knowledge of language (competence), and our ability to use it (performance) [

Chomsky 1986, 8–13] for an extended discussion). And this argument

shows how central the devaluation of text is to the theory. Yet it seems unreasonable

to argue that Swift had the innate “knowledge” that “easy to be found”

violates a grammatical principle but lacked the “ability” to apply this

knowledge in a formal, edited, poetic context, or that his editors, with the same

innate knowledge, somehow failed to notice that the sentence is ungrammatical. Errors

do find their way into print, but the existence of tens of thousands of examples

(including those with other verbs than “found”) from the seventeenth century to

the present both undermines Chomsky’s evidence for this innate principle of grammar

and supports the usefulness and validity of corpus-based text-analytic methods of

language study.

Needless to say, Chomsky’s theory does not rest entirely on this principle, and it

could be revised so as to eliminate this “knowledge” from the claimed competence

of the English speaker. Yet exceptions to principles of grammar that Chomsky claims

are universal and innate and uses as central pieces of evidence for the innateness

hypothesis are so frequent and so easily found (or easy to be found) as to suggest

that his theory will eventually have to come to terms with them if it is to survive.

Natural language corpora are becoming so large that they can now realistically be

used to test the linguist’s intuitions about what sentences are ungrammatical. And it

will not do to suggest that those who use the “deviant” passives have a

different grammar, if the deviance is derived from a principle that is claimed to be

innate. Corpora can also be used to search for grammatical structures that have not

yet been integrated into linguistic theory, and so can enrich our understanding of

human language. They can also be used to investigate the relationship between

competence and performance, or, perhaps more radically, to evaluate Chomsky’s claims

about this distinction.

Literary Theory and the Irrelevant Text

Let us turn now from the world of linguistics to the world of high theory, while

also keeping in mind the important and foundational position of Derrida’s critique of

Sassure as a connection between linguistics and theory. Despite the connection,

however, the devaluation of the text that is associated with literary theory is of a

very different kind. Rather than turning our attention from texts to the mind as an

object of study, high theory remains in the world of texts, but casts doubt on the

usefulness of approaches to the style and meaning of texts that are central to

textual analysis.

I have no quarrel with the playful and ingenious deconstruction of binaries that is

often found in deconstructive criticism. Nor do I deny the power or value of the

general poststructuralist critique that dismantles the naive view of the text as a

transparent conduit for the transmission of messages. I would like to argue instead

that skeptical doubts about the connection between words and the world are too often

taken to the extreme, that the seductive lure of skeptical relativism and very

reasonable distrust of reductive and global claims often push poststructuralist

arguments past the breaking point.

I will sketch out a few of the ways in which returning our attention to the text can

enhance our understanding and appreciation of literary texts. I will make no attempt

to be comprehensive, but will instead argue that text-centered approaches, especially

now that they can be augmented with computational tools, offer a more revealing and

more productive approach–one that can give access to kinds of information that is not

available through other means, and can at least begin to reveal how texts are

structured and how they work.

Jerome McGann, Deformance, and the Almost Irrelevant Text

Jerome McGann’s

Radiant Textuality: Literature after the

World Wide Web

[

McGann 2004] is an influential, provocative, and valuable book that

forces the reader to confront profound and important questions about the stability

of texts and the nature of interpretation. McGann uses an experiment involving the

scanning and optical character recognition of a Victorian periodical to show that

texts are unstable under one kind of machine-assisted “reading.” He argues

that instability is an inherent feature of all texts, that texts “are not containers of meaning or data but

sets of rules (algorithms) for generating themselves: for discovering,

organizing, and utilizing meanings and data”

[

McGann 2004, 138]. This is a valuable insight–one that helps

the reader to see more clearly the kinds of problems that textual editors have

long had to deal with (see Peter Shillingsburg’s

From

Gutenberg to Google, 2007 for an illuminating recent discussion). I

have argued elsewhere that McGann overestimates the instability of the text [

Hoover 2006]. Here I want to focus on the way it devalues textual

evidence and turns the critic’s attention away from the text.

One consequence of the definition of texts as algorithms for generating

themselves is that each generation is potentially unique, a product of the

algorithms and the interpreting mind. For McGann, this suggests a recuperation of

an old but recently neglected kind of performative criticism that he suggests can

open the text to interesting new readings. The performative critic practices what

McGann calls “deformance” by manipulating the order of the textual elements

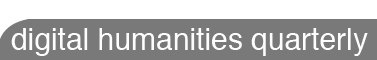

and even changing them. For example, after printing the lines of Wallace Steven’s

“The Snow Man” in reverse order, McGann argues that

deformance accentuates the intelligibility of the text and “clarifies the secondary status of the

interpretation”

[

McGann 2004, 120]. He then prints only the nouns of the poem,

leaving them in roughly their original positions and arguing that doing so shows

it to be a noun-heavy and noun-balanced poem. (The word “poem” here is

intended as uncontroversial shorthand for “poetic text.” Poems are typically

more highly structured than prose texts, and provide additional opportunities for

deformance, so that it is often important to distinguish them.)

Having practiced deformance (under the name of text alteration) for twenty-five

years, I can hardly object to it in principle. It does seem to me, however, that

the practice of textual deformance is most valuable when it is turned back upon

the original text as a tool of interpretation (see

Hoover (2004a),

Hoover (2006)). Printing

only the nouns is an effective way of focusing attention on them, and any

deformance initially requires close attention to the text. When its aims are a

better understanding of the text, it allows the critic to uncover previously

hidden relationships among the parts of the text and to examine the nature of its

self-generating algorithm. But when the focus is on performing with the poem, on

uncovering “uncommon critical

possibilities”

[

McGann 2004, 51], the critic’s attention is turned away from

the text. This turn is crucial, I would argue, precisely because the text

otherwise exercises a powerful coercive effect on interpretation and limits the

critical possibilities. Textual algorithms normally constrain or direct the

reader’s activities. Although the algorithms for generating

Jane Eyre and

Wuthering Heights were

written by sisters and published the same year, they are radically different and

lead to radically different readings. Even the amount and nature of a text’s

instability are at least partly a function of its algorithms.

There is no space here for an extended argument for textual analysis, but McGann’s

deformation of “The Snow Man” suggests an alternative,

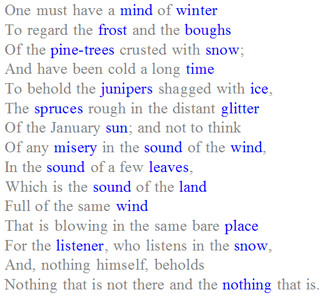

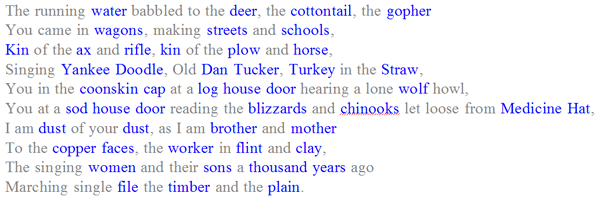

text-centered kind of marking that points in a useful direction. Below are “The Snow Man” and excerpts of about the same length from

two other poems with the nouns highlighted:

As these marked excerpts suggest, “The Snow Man” turns

out to be a noun-average poem rather than a noun-heavy one, as I have shown by

examining the frequency of nouns in twenty-five roughly contemporary poets [

Hoover 2006].

A fuller analysis of the number, character, and arrangement of nouns in poems is

worthwhile and would almost certainly lead to further insights about the poems

(see [

Hoover 2006] for more discussion; also [

Hoover 2007]). Even a brief inspection of these excerpts, however,

shows that the nouns in Sandburg’s poem are not only much more frequent than those

in “The Snow Man,” they are much more concrete and

specific. They ground and localize the fictional world of the poem much more fully

than do the nouns of “The Snow Man,” and their rural

and regional flavor is unmistakable. In Millay’s poem, the nouns are much less

frequent than those in “The Snow Man,” and they seem

relatively prosaic. The power of the poem lies elsewhere.

Printing only the nouns of a poem in their original positions in the poem can

lead to a wider investigation into the kinds, frequencies, and placements of nouns

in other poems, via textual or corpus analysis. Such an investigation can tell us

a great deal about Stevens’s poem and about modern poetry more generally. Instead,

however, McGann turns away from the poem toward his own algorithm, arguing that

printing only the nouns “enhances the

significance of the page’s white space, which now appears as a poetic

equivalent for the physical ‘nothing’ of snow”

[

McGann 2004, 123]. Rather than focusing on the poem, he bases

his reading on the white space of a poem Stevens did not write, white space that

is present in any poem deformed in this way, whether or not whiteness or snow is

in any way relevant to its interpretation. This kind of argument abandons all hope

of persuasion or consensus and turns criticism into a purely subjective and

self-indulgent activity.

Consider the following deformation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The

Raven”:

Note how this deformation enhances the significance of the black type, allowing it

to appear as a poetic equivalent of the physical “nothing” of the blackness

of the Raven. If you look closely, you can see the raven’s beady eyes peeking over

the top of the first line. If you look again, you can see how Poe anticipated the

Borg ship from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Being

provocative is just not enough, and the black and white nature of most printed

text assures that symbolism based on black ink or white paper is unlikely to be

more than coincidentally relevant. The currency of ideas still stranger than those

in McGann’s book in published literary criticism rather proves than disproves my

point.

Stanley Fish and the Missing Inuit

Stanley Fish is another provocative thinker whose provocations radically devalue

the text and push the reader away from an important source of insight. Although

Fish’s thought has had many phases, I am concerned here with his early and very

influential book,

Is There a Text in this Class?

[

Fish 1980]. There, Fish reports and critiques a comment by Norman

Holland about unacceptable readings — a comment based on an unusual interpretation

of the following passage from Faulkner’s “A Rose for

Emily”:

That was when people had begun to feel

really sorry for her. People in our town, remembering how old lady Wyatt, her

great-aunt, had gone completely crazy at last, believed that the Griersons held

themselves a little too high for what they really were. None of the young men

were quite good enough for Miss Emily and such. We had long thought of them as

a tableau; Miss Emily a slender figure in white in the background, her father a

spraddled silhouette in the foreground, his back to her and clutching a

horsewhip, the two of them framed by the back-flung front door. So when she got

to be thirty and was still single, we were not pleased exactly, but vindicated;

even with insanity in the family she wouldn't have turned down all of her

chances if they had really materialized.

[Faulkner 1978, 434]

Holland suggests that if a reader believed that the “tableau” above

“described an Eskimo,” he or she would not be thought of as “responding to the story at all–only pursuing

some mysterious inner exploration”

[

Fish 1980, 346]. Fish agrees that the Eskimo reading is

unacceptable, but argues that it is unacceptable not because the text does not

support it, but because no current interpretive strategy exists for producing such

a reading:

While there are always mechanisms for

ruling out readings, their source is not the text but the presently

recognized interpretive strategies for producing the text. It follows, then,

that no reading, however outlandish it might appear, is inherently an

impossible one.

[Fish 1980, 347]

He imagines someone finding a letter in which Faulkner says he always believed he

was an Eskimo changeling and suggests that Faulkner critics would then “transform the text into one informed

everywhere by Eskimo meanings.”

[

Fish 1980, 346]

Fish’s argument is as specious as it is clever. Holland’s example of an Eskimo

reading is clearly chosen so as to avoid any resonance with the text: most readers

will know only a little stereotypical information about Eskimo culture, and an

igloo would not last very long in Yoknapatawpha County. (Eskimo is

now normally replaced by Inuit. The changing political status of

words like Eskimo is an area in which Fish’s point about the changing

meaning of texts is valuable, though not very provocative or controversial.) It

might be possible to integrate the (widely misunderstood) practice of wife sharing

into the tableau in some bizarre way, but if Fish’s point is only that we are

quite adept at finding what we want to find, that is hardly a novel or provocative

idea, and is certainly not a critical method that should be encouraged.

A letter from Faulkner revealing that he always thought of himself as an Inuit

changeling is unlikely to be sufficient to support an Inuit reading. How would

being a changeling imbue his texts with Inuit meanings in any case? What is

signally missing from “A Rose for Emily” is any actual

textual reference to Inuit culture, and Holland’s point is far more specific than

the version Fish rejects: being “informed” by Inuit readings is not much like

“describing an Eskimo,” so that Fish’s imagined letter is simply

irrelevant to Holland’s point. (Note that the claim that the meaning is not in the

text effectively insulates Fish against this kind of criticism.) If critics really

reacted as Fish suggests they would, so much the worse for criticism, but it seems

far more likely that, because of the nature of Faulkner’s texts,

either such a letter would be rejected as a forgery or critics would wonder why

being a changeling had so little influence on his writing. Readings can and do

change over time, sometimes radically, and critics like Fish are partly

responsible for the current tolerance for a greater distance between the text and

its interpretation than might have existed in the past. Still, interpretations are

not as independent of the text as Fish suggests, and he ignores the huge overlap

between even the most violently contrasting interpretations, the sources of which,

given the variety among the interpretive communities that he suggests are

responsible for the interpretations, surely include the text. For that matter, it

is difficult to imagine the formation of the kind of interpretive community Fish

posits in the absence of a body of shared texts.

Professor Fish, is there a textbook for this course?

One of Fish’s most famous examples, “Is

there a text in this class?”, the title of his book, is also deeply

problematic. A student who has just taken a class from Fish asks this question on

the first day of class of another professor who takes it to be a question about

whether there is a required textbook. The student corrects the professor: “No, no . . . I mean in this class do we

believe in poems and things, or is it just us?”

[

Fish 1980, 305]. Fish’s insistence on the importance of

context for interpretation is valuable, and it provides a welcome change from the

single-sentence focus of Chomskyan linguistics. Of central importance here is his

claim that we interpret such a sentence by virtue of belonging to an interpretive

community in which it makes sense and not by virtue of the meanings of its words

or their syntactic relationships. In what follows I will focus on this claim, but

also on the question itself and what he has to say about it.

Fish discusses the two meanings of the question above and suggests a third

possibility — that the student is asking about the location of her misplaced book

(my paraphrases follow each one):

- Is there a text in this class?1 Is there

a required textbook for this course?

- Is there a text in this class?2 Will this

course assume the meaningfulness of texts?

- Is there a text in this class?3 Is my

misplaced textbook in this classroom?

[Fish 1980, 306–7]

He argues that all of these are literal, and that they all arise out of the

context, not out of the text. It is a tribute to Fish’s skill at argumentation

that the extreme form of his position has been taken seriously. It is apparent,

for example, that the words of the sentence and their syntactic arrangement deeply

influence all three of these meanings (how did the professor know it was a

question?), and that the crux of the matter is the ambiguity of “text,”

“in,” and “class” that my paraphrases highlight. Given the importance he

places on interpretive communities, it is surprising that Fish refuses to

acknowledge one of the largest and most important of the interpretive communities

relevant to this example: speakers of English. In that community, there are such

things as meanings of words (of course not Platonic forms or Aristotelian

categories), meanings that are, as he rightly points out, more or less profoundly

affected by the context of use, broadly understood to include things like the

other interpretive communities to which the professor and student belong.

Given Fish’s valuable emphasis on the contextual nature of meaning, it also seems

surprising that the text should be denied a part in the creation of that meaning.

Fish is surely right that the relationships, contexts, and interpretive

communities that surround or constitute his classroom tableau, as well as the

personal histories of the student and professor are crucial to the professor’s

understanding of the student’s question, and to her ability to produce it. But the

question itself is also an important element in the entire exchange. “What are

your office hours?” spoken in the identical context (first day of class, the

same student and professor, etc.) obviously means something very different and

calls for a radically different set of possible answers. However problematically,

the sources of difference must include the language of the question. The practice

of holding office hours, their nature, their typical format and scheduling and

their institutional status–all of their meaning in the academic interpretive

community–is partially dependent on the words “office” and “hours” and

how those words are used, both in English generally, and within that community. To

put it another way, one of the chief ways one becomes a member of an interpretive

community is by learning to understand and respond to its texts appropriately.

But let us return to the text. Fish suggests that, while none of the meanings is

the only literal one, “Is there a required textbook for this course?” is

“more normal” than “Will this course assume the meaningfulness of

texts?” (he does not further discuss the third meaning). He argues that the

first meaning has a broader context of understanding (the participants need only

know roughly what is normal in the context of the first day of class), and the

second a narrower, more specialized one (the participants need to know something

about Fish’s literary theory). The fact that the student and the professor could

only have come to the required knowledge through reading and listening to Fish’s

ideas, however, makes his cavalier neglect of the words of the text seem little

more than a debater’s trick.

But if we use corpora to investigate the crucial phrase “text in this class”

and some variants of it, we gain access to evidence about how that huge

interpretive community called “speakers of English” actually uses the phrase.

Unfortunately, the phrase is not common enough for the BNC to be of much use,

though the fact that the only instance of “text in this class” in the BNC is

a reference to the title of Fish’s book is significant, as will become clear

shortly. Turning again to Google (search for “text in this class”, 7/20/06),

we find that nearly 90% of about 31,200 uses of the phrase are direct references

to Fish’s book, and only about 6% mean “Is there a required textbook for this

course?” (My counts are based on a manual examination of 500 hits taken from

throughout the 1,000 that Google provides; the results should be taken as

suggestive rather than in any way definitive.) This proportion is a tribute to the

importance of the book since 1980. A search for “text for this class” returns

about 18,300 hits, almost all of which mean “Is there a required textbook for

this course?” Here are the frequencies of some related phrases, with those

already discussed repeated for clarity:

| text for this class |

18,300 |

| text in this class |

31,200 |

| texts for this class |

890 |

| texts in this class |

200 |

| text for this course |

81,600 |

| text in this course |

750 |

| texts for this course |

31,100 |

| textbook for this class |

19,600 |

| textbook in this class |

110 |

| textbooks for this class |

450 |

| textbooks in this class |

20 |

| textbook for this course |

102,000 |

| textbook in this course |

80 |

| textbooks for this course |

93,200 |

| syllabus for this class |

10,300 |

| syllabus in this class |

50 |

| syllabus for this course |

52,700 |

| syllabus in this course |

100 |

Currently, it would seem, “text in this class” is quite an unusual way of

indicating “textbook for this course,” the meaning that Fish suggests is the

most normal. The preposition “for” is normal while “in” is unusual:

overall, not counting “text for/in this class,” phrases with “for” are

almost 200 times as frequent as those with “in.” Furthermore, “course”

and “textbook” are more frequent than “class” and “text.” The

professor’s initial interpretation is (obviously) a possible one, and it may be

more normal now than in 1980 because of the influence of the book. The context in

which the question occurs is part of what makes it possible, but the evidence of

usage (the actions of an enormous interpretive community) confirm that the form of

the question is highly relevant to its interpretation and to the context in which

it is used. And even if the evidence presented here is not accepted as definitive,

it must be remembered that Fish provides no evidence at all for his claims about

the three possible meanings for the question. His assertions are based purely on

intuition.

William Golding, Stanley Fish, and the Significance of Shrinking Sticks

Finally let us consider Fish’s famous attack on stylistics, “What is Stylistics and Why are They Saying Such Terrible Things About

It?”, chapter two of

Is There a Text in This

Class?

[

Fish 1980]. I do not want to rehash this old debate, but rather to

discuss one central literary example he raises. Fish rejects M. A. K. Halliday’s

analysis of William Golding’s second novel,

The

Inheritors, and specifically the link that Halliday asserts between the

linguistic characteristics of the text and its interpretation.

The Inheritors is told from the point of view of a

Neanderthal named “Lok,” as his people are invaded and destroyed by more

modern humans, and our sentence for discussion appears in bold type in the

following passage from the novel:

The man turned sideways in the bushes and looked at Lok along his shoulder.

A stick rose upright and there was a lump of bone in the middle. Lok peered

at the stick and the lump of bone and the small eyes in the bone things over

the face. Suddenly Lok understood that the man was holding the stick out to

him but neither he nor Lok could reach across the river. He would have

laughed if it were not for the echo of the screaming in his head. The stick began to grow shorter at both ends. Then it

shot out to full length again.

The dead tree by Lok's ear acquired a voice.

“Clop!”

His ears twitched and he turned to the tree. By his face there had grown a

twig: a twig that smelt of other, and of goose, and of the bitter berries

that Lok's stomach told him he must not eat. [Golding 1955, 106]

As this brief excerpt shows, the novel’s limited point of view presents

difficulties of interpretation for the reader: Lok does not know what bows and

arrows are and cannot (yet) imagine one person attacking another, but Golding must

make us see that the man has just shot a poisoned arrow at him. Halliday’s

analysis argues that the reader’s difficulty is at least partly explained by the

peculiar Neanderthal notion of agency, in which a stick might change length by

itself, and by the novel’s limited vocabulary, in which there are no arrows or

arrowheads, no bows or the drawing of them, and no poison, but rather “a

twig,”

“a lump of bone,”

“a stick,” and “bitter berries.” Fish rejects Halliday’s claim that the

unusual features of the text force the reader to reinterpret “The stick began to

grow shorter at both ends” as the drawing of the bow:

The link between the language and any

sense we have of Neanderthal man is fashioned in response to the demands of

the reading experience; it does not exist prior to that experience, and in

the experience of another work it will not be fashioned, even if the work

were to display the same formal features. In any number of contexts, the

sentence “the stick grew shorter at both ends” would present no

difficulty for a reader; it would require no effort of reinterpretation, and

therefore it would not take on the meaning which that effort creates in

The Inheritors.

[Fish 1980, 84]

Fish may be right that a reader will not necessarily understand this sentence to

mean that a bow has been drawn without the context in which it occurs, but my

experience has been that the passage alone is sufficient context for many readers.

(It seems pointless to quibble that he has misquoted the sentence; if the text is

not the source of the meaning, that should be irrelevant in any case.) But in any

context, the sentence shapes any normal reader's interpretation in very definite

ways–simply by virtue of its grammatical and lexical characteristics and the

grammar and lexicon of English that the reader has learned. The reader must find

some way of assimilating the fact that the stick changes length by itself, and

most readers will reinterpret this sentence by adding the agency that Lok does not

understand.

I have suggested that this sentence might seem relatively normal in a description

of a magic trick or a campfire [

Hoover 1999, 23–4], but an

examination of its occurrences in large corpora suggests further ramifications

that I had not considered: “grow shorter” is essentially an oxymoron, and so

might be expected to be uncommon. The metaphor of “becoming larger is

growing” is a cognitively grounded one in which increasing in size is

modeled on growth, our preeminent natural example of increase in size, and one

that we have all intimately experienced. Inanimate objects do not generally

increase in size without an external cause, and the best examples for the metaphor

are glaciers, rivers, lakes, lava flows, avalanches, and objects like snowballs

rolling down hills, balloons, or crystals. The best examples of decrease in size

are compression, shrinking, erosion, melting, and deflation.

Without “stick” the phrase “grow shorter” seems quite ordinary, in

spite of being an oxymoron, and there are ten examples of a form of “grow”

followed by “shorter” in the BNC:

- The architecture of triticale was altered so that it would grow

shorter

- new selection pressure, and will be pushed towards growing shorter

coats again.

- Nevertheless, I worry about you as the days grow shorter

- As the days grew shorter, the Rectory colder, the pleasure they

took

- emotional and intellectual life as the autumn days grew shorter

- [estimates of] around 2,000 million years, have been growing shorter

anyway

- all of them found their attention span had grown shorter

- [nylon cords] may be showing signs of old age, knotted and growing

shorter

- The stick began to grow shorter at both ends

- The stick began to grow shorter at both ends.

It seems quite significant that two of the ten examples even of this relatively

ordinary phrase are quotations from

The Inheritors.

Only the first two of the ten use “grow” in the biological sense. In all the

others “grow” can be replaced by “become” and only the sentence from

The Inheritors describes an object changing size

in real time. In comparison, there are thirty-nine examples of a form of

“grow” followed by “longer” in the BNC. Perhaps surprisingly, only

nine of these refer to biological growth, and none of the thirty-nine describes an

object changing size in real time. (Surprises are the norm when reading a

concordance [

Sinclair 2003], [

Sinclair 2004]). Phrases

with forms of “become” instead of “grow” are even less frequent.

A Google search for forms of “grow shorter” (7/20/06) returns tens of

thousands of hits, but an examination of several hundred of them suggests that

things that grow shorter tend to fall into a few main categories:

- days and other periods of time, cycles, hospital stays

- articles of clothing, hair, body parts and plant parts (become shorter

over time, or from one generation to the next)

- temper, patience

- meetings, lectures, speeches, phone calls, letters, lists, sentences,

words

- distances

- fuses, candles, cigarettes, cigars, wicks

It is easy to see that the predominant meaning of “grow shorter” is

“become shorter”, that the process of shortening is typically one that

takes place in stages (especially for physical objects), and that many of the

things that become shorter are abstract. By far the most frequent item that grows

shorter is “days,” as the BNC list above also suggests (“grow shorter”

returns more than 100,000 hits; “days grow shorter” returns more than

55,000). When physical objects actually diminish in size, they are usually being

consumed by fire. Finally, there is a smattering of examples that are relevant to

The Inheritors: those that belong to the realms of

fantasy and magic, including transformation stories and role-playing games.

Textual evidence shows that even the relatively ordinary “grow shorter” is

significantly constrained, especially when the subject of the verb is a physical

object and the change is taking place in the present, in real time. And this

evidence supports Halliday’s claims about the oddness of Golding’s sentence and

suggests a cause for the reader’s reaction.

Returning to the full sentence makes this point more forcefully. A Google search

for “the stick began to grow shorter at both ends” (7/20/06) returns only

eight hits, all quotations from The Inheritors, and

dropping “at both ends” returns four additional slightly variant quotations.

A more recent search (7/2/07) returns twenty-one hits, but all are still from the

novel, as are the eight additional hits returned by dropping “at both ends.”

Many six-word sequences from novels will return only quotations as hits, however,

so that it seems reasonable to expand the search by focusing on the crux of the

sentence: “stick grew shorter.” This returns only four additional hits: one

is a paraphrase of Golding, two are duplicates in which a walking stick is worn

away on a long journey, and in the other the stick shortens as it burns. There is

one example of “[observed my searing] stick grow shorter”, which refers to

smoking a cigarette. There are no hits for “stick grows shorter”, but an

earlier search (12/22/05) returned one example referring to cigarette smoking. A

search for “stick grew longer” returns only one hit, in a history of hockey,

where it describes the use of successively longer sticks, but there were three

other interesting hits in my earlier search, one a dream sequence in which a sharp

stick threateningly lengthens toward the dreamer’s face and two pieces of fantasy

fiction, one of which involves the explicit use of magical dust. Fish’s claim that

Golding’s sentence would present no difficulty in “any number of contexts”

begins to seem quite doubtful, and a text-analytic corpus approach both provides

unexpected insights and gives us access to evidence about how sentences are

used–evidence that seems far more reliable than that of unaided intuition.

A much larger corpus would be useful in examining how and what Golding’s sentence

means, but the examples I have found suggest that sticks grow shorter only in

extremely limited contexts outside Golding’s novel, either in relatively prosaic

contexts where they are burnt up or wear away, or in the fantastic contexts of

dreams and magic. Golding’s sentence has precisely the effect Halliday claims for

it: it pushes us into a (necessarily fantastic) Neanderthal world in which

inanimate objects are not really inanimate, in which Lok’s feet are “clever”

and can see, in which logs might crawl off on business of their own. In which

passages like this make sense:

“The stone is a good stone,” said Lok. “It has not gone away. It

has stayed by the fire until Mal came back to it.”

He stood up and peered over the earth and stones down the slope. The

river had not gone away either or the mountains. The overhang had waited

for them. Quite suddenly he was swept up by a tide of happiness and

exultation. Everything had waited for them: Oa had waited for them. Even

now she was pushing up the spikes of the bulbs, fattening the grubs,

reeking the smells out of the earth, bulging the fat buds out of every

crevice and bough. [Golding 1955, 31–2]

Part of the power of “the stick began to grow shorter at both ends” is in the

shape of Lok’s incomprehension. For Lok, the whole world is alive, so that a stick

that changes length is perfectly comprehensible. Readers of the novel, which is

full of passages like the one above, come to see this animistic view as no mere

personification, but rather as an integral part of Lok’s world view, his mind

style. They also comprehend what he does not, until it is too late–the murderous

agency of his enemy, the bender of the bow.

It is true that an appropriate context is required to interpret Golding’s

Neanderthal world, as Fish so forcefully argues, but to focus only on the

interpretive community as a source of possible interpretations of texts is not

only to ignore the creative acts of the writers who created those texts, but also

to deny ourselves access to the most crucial element of the context in which a

reader interprets The Inheritors: the novel itself.

Any theoretical position that ignores, devalues, or rejects the text merely

encourages sloppy thinking and foolish interpretations.

Conclusion

It is time for a return to the text, specifically the electronic, computable text, to

see what scholarly digital editions, corpora, text-analysis, statistical stylistics,

and text-alteration can reveal about meanings and style. Scholarly digital editions

deepen our understanding of texts even as they problematize them, especially by

providing easy access to multiple versions of texts. Corpus analysis can reveal

hidden “semantic prosodies” and

multi-word meaning structures that have eluded thousands of years of textual study

[

Louw 1993], and can clarify and confirm the meaningfulness of a

text’s vocabulary. It can even be used to fine-tune a translation by selecting words

with appropriate frequencies and contexts [

Goldfield 2006]. Contra

Chomsky, McGann, and Fish, we can

Trust the Text

[

Sinclair 2004]. Corpora can also provide usable norms for stylistic

analysis and genre definition [

Biber 1995], and can show that authentic

texts offer a surer basis than introspection for linguistic analysis. While

recognizing the contribution of the reader, text-analysis can reveal kinds and levels

of meaning that are otherwise unrecoverable [

Stubbs 1996], and

statistical stylistics and authorship attribution can provide powerful new tools for

understanding the statistical basis of style [

Burrows 2002a], [

Burrows 2002b], [

Burrows 2002b], [

Burrows 2007], [

Hoover 2004b], [

Hoover 2004c], [

Hoover 2007]. Finally, even the easy malleability of electronic

texts can be put to more constructive uses: altering a literary text is often the

most effective way of understanding it [

Hoover 2004a], [

Hoover 2006]. There is much to be done, and many more ways of doing it

than I have described, but the stage seems finally set for a much fuller realization

of the value of electronic texts, for the end of the irrelevant text.

Works Cited

BNC World 2001

The British National Corpus, version 2 (BNC World). Distributed by

Oxford University Computing Services on behalf of the BNC

Consortium, 2001.

http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk

Biber 1995

Biber, D.

Dimensions of Register Variation: A Cross-linguistic

Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.

Press, 1995.

Burrows 2002a

Burrows, J. F.

“The Englishing of Juvenal: Computational Stylistics and

Translated Texts”. Style

36 (2002): 677-99.

Burrows 2002b

Burrows, J. F.

“

‘Delta’: A Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely

Authorship”. Literary and Linguistic Computing

17 (2002): 267-287.

Burrows 2007

Burrows, J. F.

“All the Way Through: Testing for Authorship in Different

Frequency Strata”. Literary and Linguistic

Computing

22 (2007): 27-47.

Chomsky 1975

Chomsky, N.

Reflections on Language. New York:

Pantheon Books, 1975.

Chomsky 1986

Chomsky, N.

Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use.

New York: Praeger,

1986.

Chomsky 2000

Chomsky, N.

New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind.

Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press,

2000.

Faulkner 1978

Faulkner, W.

“A Rose for Emily”. In R. V. Cassill, The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction (3rd ed.), New

York: Norton, 1978, 431-38.

Fish 1980

Fish, S.

Is There a Text in This Class?

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University

Press, 1980.

Goldfield 2006

Goldfield, J.

“French-English Literary Translation Aided by Frequency

Comparisons from ARTFL and Other Corpora”. Digital

Humanities 2006. Paris: Centre de

Recherche Cultures Anglophones et Technologies de l’Information,

2006, 76-8.

Golding 1955

Golding, W.

The Inheritors. London:

Faber & Faber, 1955.

Halliday 1981

Halliday, M. A. K.

“Linguistic Function and Literary Style: An Inquiry into the

Language of William Golding's The Inheritors”. In D. C. Freeman, Essays in Modern Stylistics, London:

Methuen, 1981, 325-60.

Hoover 1999

Hoover, D. L.

Language and Style in The Inheritors. Lanham,

Md: University Press of America,

1999.

Hoover 2004a

Hoover, D. L.

“Altered Texts, Altered Worlds, Altered Styles”. Language and Literature

13(2) (2004): 99-118.

Hoover 2004b

Hoover, D. L.

“Delta Prime”? Literary and

Linguistic Computing

19 (2004): 477-495.

Hoover 2004c

Hoover, D. L.

“Testing Burrows’s Delta”. Literary

and Linguistic Computing

19 (2004): 453-475.

Hoover 2006

Hoover, D. L.

“Hot-Air Textuality: Literature after Jerome McGann”.

Text Technology, 15(1) (2006): 75-107.

Hoover 2007

Hoover, D. L.

“Corpus Stylistics, Stylometry, and the Styles of Henry

James”, Style

41(2) (2007): 160-189.

Louw 1993

Louw, B.

“Irony in the Text or Insincerity in the Writer? The Diagnostic

Potential of Semantic Prosodies”. In M. Baker, G. Francis, and E.

Tognini-Bonelli, Text and Technology.

Philadelphia: Benjamins,

1993, 157-76.

McGann 2004

McGann, J. J.

Radiant Textuality: Literature After the World Wide Web.

New York: Palgrave,

2004.

Sampson 2005

Sampson, G.

The “Language Instinct” Debate (rev. ed.).

London: Continuum, 2005.

Shillingsburg 2006

Shillingsburg, Peter L.

From Gutenberg to Google: Electronic Representations of Literary

Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.

Press, 2006.

Sinclair 2003

Sinclair, J.

Reading Concordances: An Introduction.

Harlow: Longman,

2003.

Sinclair 2004

Sinclair, J.

Trust the Text: Language, Corpus and Discourse.

London: Routledge,

2004.

Stubbs 1996

Stubbs, M.

Text and Corpus Analysis: Computer-Assisted Studies of Language

and Culture. Oxford:

Blackwell, 1996.

Trillin 1998

Trillin, C.

“The Trouble with Transcripts”. Time

151.19 (May 18, 1998): 34.