Abstract

This article describes Mediate: An Annotation Tool for Audiovisual Media,

developed at the University of Rochester, and emphasizes the platform as a source

for the

understanding of film, television, poetry, pop songs, live performance, music, and

advertising as shown in three cases studies from film and media studies, music history,

and linguistics. In each case collaboration amongst students was not only key, but

also

enabled by Mediate, which allows students to work in groups to generate large

amounts of data about audiovisual media. Further, the process of data generation produces

quantitative and qualitative observation of the mediated interplay of sight and sound.

A

major outcome of these classes for the faculty teaching them has been the concept

of

audiovisualities: the physically and culturally interpenetrating modes of

audiovisual experience and audiovisual inscription where hearing and seeing remediate

one

another for all of us as sensory and social subjects. Throughout the article, we chart

how

audiovisualities have emerged for students and ourselves out of digital annotation

in

Mediate.

Introduction[1]

It has long been a premise in the study of media that multiple senses are in play

when we

view movies, watch television, listen to live or recorded music, read or hear poems

read

aloud, and consume advertising, whether in print or on screens [

Benjamin 1939]

[

McLuhan 1964]

[

Hansen 2004]. Since the late twentieth century, the interplay of seeing and

hearing has yielded richly variegated writing and thinking about, on the one hand,

vision

and visuality and, on the other, the acoustic, the audible, and the aural. In this

essay,

we pursue this interplay into the digital humanities. More specifically, we advance

the

concept of

audiovisualities in order to describe that interplay in the

context of digital annotation of time-based media. In these media, seeing and hearing

are

inseparable and our goal is to understand how processes of digital annotation can

help

scholars and students investigate this entanglement. To do this, we describe a platform

we

have named

Mediate: An Annotation Tool for Audiovisual Media, which was

developed with the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Rochester and has

been

used in undergraduate courses across the humanities and social sciences there. In

these

settings,

Mediate has enabled our students and ourselves to see and hear the

data of our eyes and ears in reflexively collective and recursively interdisciplinary

ways. This collective process in a variety of classrooms is what has brought us —

three

faculty members (two tenure track, one instructional track), two students (an

undergraduate and a graduate student), and two staff members from the library (the

programmer and the Director of the Digital Scholarship Lab) — to the concept of

audiovisualities we explore in this essay.

That concept cannot be disaggregated from visual studies and sound studies, two fields

that have developed alongside their more disciplinary counterparts in art history,

film

studies, musicology, and music theory. Broadly conceived, visual studies offers a

means of

understanding the expansive domain of the visual beyond what disciplines such as art

history or film studies allow us to see. Wildly diverse in the directions it has taken

since emerging in the late twentieth century, one of the central legacies of visual

studies has been the concept of "visuality," or "sight as a social fact," which cannot

be

disaggregated from the act of "vision," or "sight as a physical operation" [

Foster 1988]. Adapting W. J. T. Mitchell, we can think of visuality as a

"dialectical concept" in which the study of "visual culture cannot rest content with

a

definition of its object as the social construction of the visual field, but must

insist

on exploring the chiastic reversal of this proposition,

the visual construction of

the social field. It is not just that we see the way we do because we are social

animals, but also that our social arrangements take the forms they do because we are

seeing animals" [

Mitchell 2002].

As in visual studies, scholars working in sound studies, which took identifiable shape

in

the early twenty-first century, refuse to be content with a definition of its object

as

solely the social construction of the sonic field, but also account for the sonic

construction of the social field [

Bull 2013]

[

Novak and Sakakeeny 2015]

[

Pinch and Bijsterveld 2012]

[

Sterne 2012]. Pushing beyond logocentric and ocularcentric theoretical

frameworks in various established disciplines, sound studies treats the audible and

the

aural, as Jonathan Sterne has put it, as "an artifact of the messy and political human

sphere" [

Sterne 2003]. Pondering that "artifact," three researchers

exploring what they call "digital sound studies," including one of the authors of

this

article, have posed a question about the assumed modes in scholarship itself. "How,"

they

ask, "can scholars write about sound

in sound?" [

Lingold et al. 2018].

A key effect that sound studies has had on visual studies has been to remind those

working in the latter that the sights we see often go hand in hand with the sounds

we

hear. While Sterne's work in

The Audible Past has systematized and

historicized this sight-sound relation, film theorists such as Michel Chion [

Chion 1994] and Kaja Silverman [

Silverman 1988] and media

archeologists such as Siegfried Zielinski [

Zielinski 1999]

[

Zielinski 2006] and Bernard Stiegler [

Stiegler 2014] have

generatively tracked the dialectic of the visual and the audible in their work. We

think

of this dialectic as producing the audiovisualities — the physically and culturally

interpenetrating modes of audiovisual experience and audiovisual inscription where

hearing

and seeing remediate one another for all of us as sensory and social subjects — that

this

essay aims to chart in relation to digital annotation in

Mediate.

At the University of Rochester, students have used

Mediate to annotate

cinematic, televisual, musical, literary, and commercial media in courses housed in

the

Film and Media Studies Program, the Musicology Department, and the Department of

Linguistics. In these courses, the audiovisual specificities of a given medium become

radically legible to students in the data they yield by annotating in

Mediate. Further, as we will show in this article, in exploring the

medium-specific qualities of film or music or advertising in their unique material

forms,

cultural contexts, and social functions, we have unexpectedly ended up in a broader

concept of audiovisuality that cuts across disciplinary differences. To riff on Mitchell

one last time,

Mediate allows us to examine the audiovisual construction of

the social field as much as the social construction of the audiovisual field. Through

the

annotation it supports,

Mediate provides a platform in which that field is no

longer immediately intuited through our senses, but turned into an object of analysis

— an

audible and visible "exteriority" [

Sterne 2003] that allows us to grasp the

interplay of seeing and hearing beyond the often self-contained ways in which we process

sensory data internally and individually.

Mediate and the Audiovisual State of Digital Annotation

Mediate arose out of Joel Burges's desire to have a digital tool that would

enable the collection of large amounts of data about how time works on television.

Originally working with Nora Dimmock, Jeff Suszczynski, and Joshua Romphf by experimenting

with digital humanities projects in the classes "The Poetics of Television," "Film

History, 1989-Present," and "Clocks and Computers: Visualizing Cultural Time" between

2012

and 2016, this desire gave way to the still ongoing project of developing a digital

annotation tool for audiovisual media that would be of more general use. As it did,

we

moved from combining software such as Jubler, DaVinci Resolve, and Adobe Encore to

building our own platform, primarily through the labor of Romphf [

Burges et al. 2016].

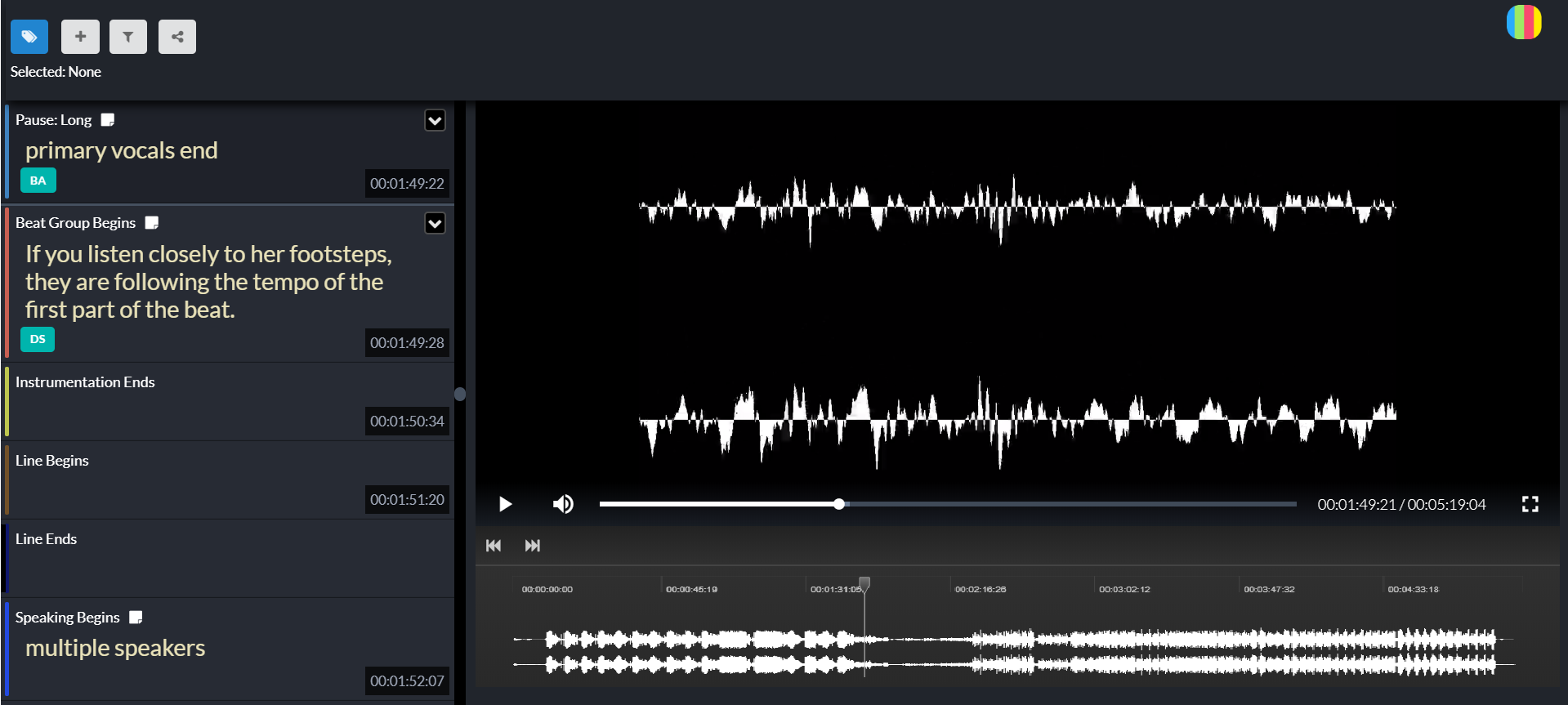

Mediate is a web-based platform that allows users to upload audiovisual

media; produce real-time notes; generate automated and manual annotations (which we

also

call markers) on the basis of customized schema; preserve the annotations as data

that can

be queried; and export the data in CSV and JSON formats for further exploration,

interpretation, and visualization. The platform is built in Python and JavaScript,

and it

makes use of several open source libraries, including Django, OpenCV, FFMPEG, and

React.

Through websockets tied together by a REST API,

Mediate supports concurrent

updates of annotations added by multiple users.

Mediate provides a real-time

system for annotating and analyzing myriad genres that yield audiovisualities in which

sight and sound come into chiastic interplay in medium-specific ways.

There are other tools like

Mediate, including ELAN and NVivo, the subjects

of a recent study of the audiovisual state of digital annotation [

Melgar et al. 2017]. The build of ELAN and NVivo, however, make them technologically and methodologically

distinct from

Mediate. NVivo is not open source, while ELAN is — we hope

Mediate will be open source and widely accessible in the future. Both ELAN

and NVivo are desktop-based programs and have limited collaborative capabilities,

whereas

synchronous and asynchronous collaboration are foregrounded in

Mediate. ELAN

projects can only contain one media file whereas NVivo has a more multimodal approach

and

supports a variety of file formats, similar to

Mediate. ELAN provides tiers

(like the schema we use in

Mediate, described below) with controlled

vocabularies (akin to markers that make up schema in

Mediate, again described

below), whereas the categorization in NVivo is done after annotating through a code

book

approach common in the social sciences. Neither tool offers, as

Mediate does,

automated shot detection, and the ease of querying and exporting data across projects,

media, and/or schema. Furthermore, they both feature high learning curves.

Mediate adopts a more streamlined approach to consuming media in the design

of its interface, which echoes familiar interfaces from our historical moment.

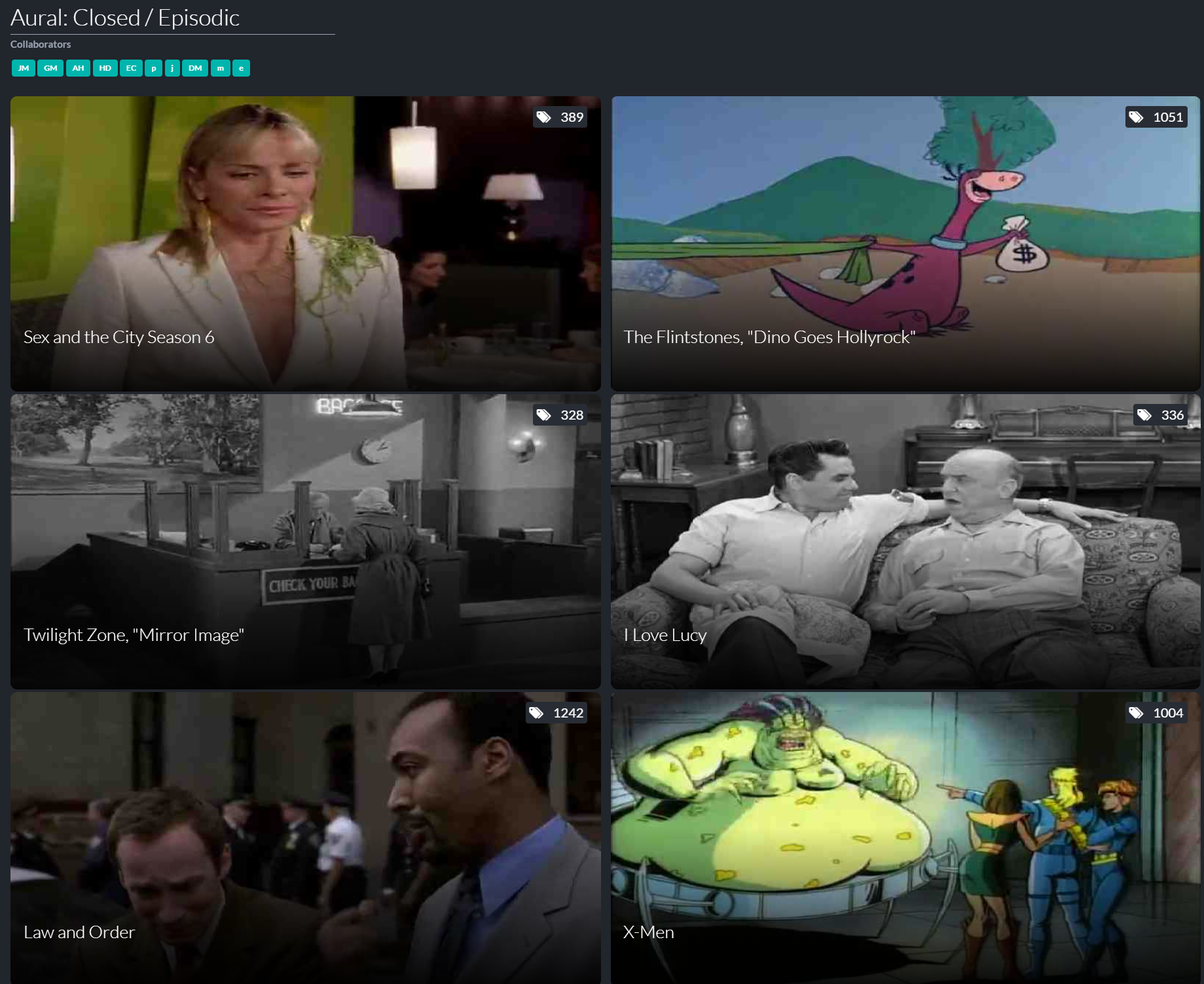

When a user logs into the Mediate website (username: mediate_guest password:

mediate2019!), they encounter the User Interface that displays their research groups.

Each

group includes the initials of the members along with the media assigned to the group.

The

media thumbnails include a count in the upper right-hand corner for annotations already

generated.

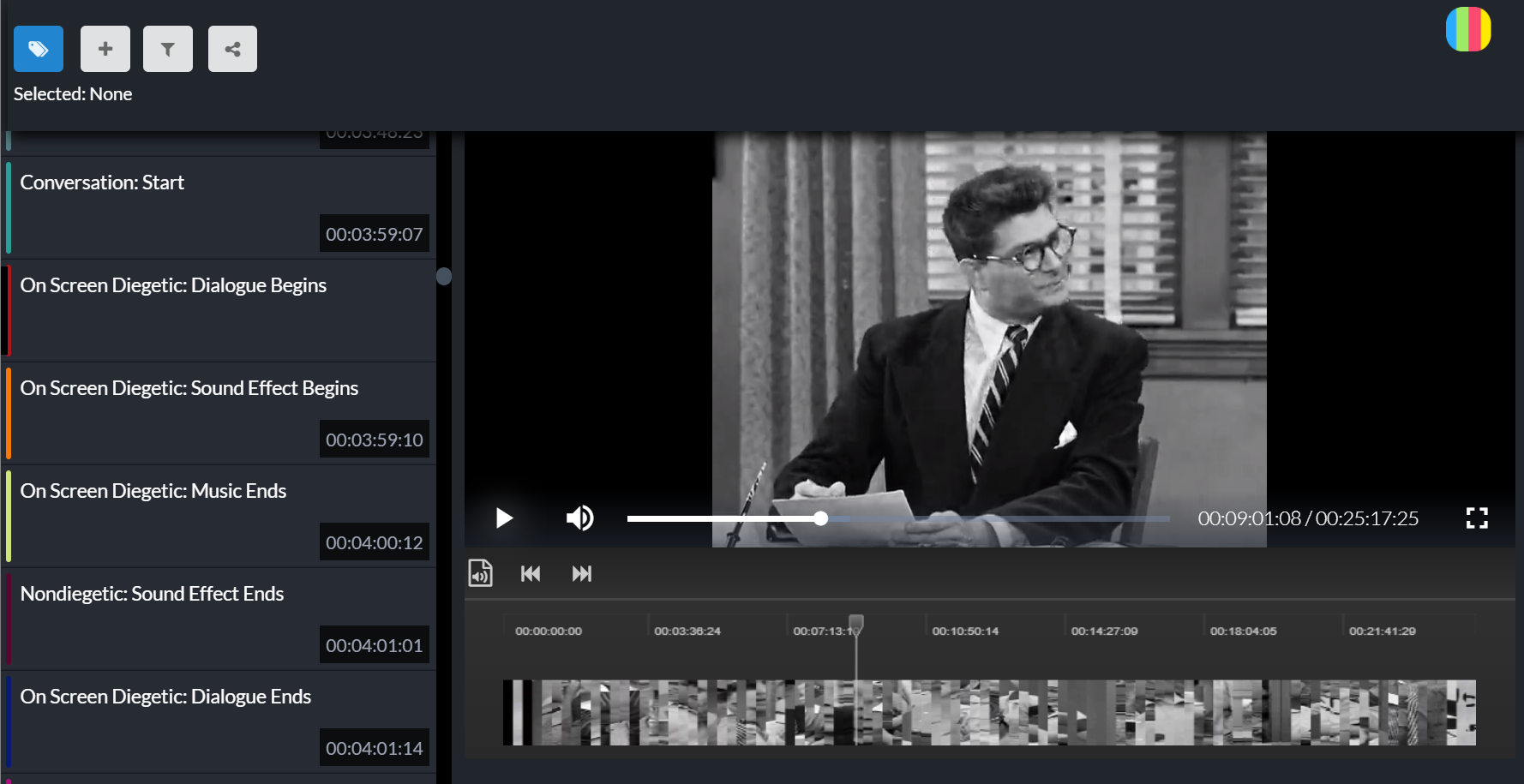

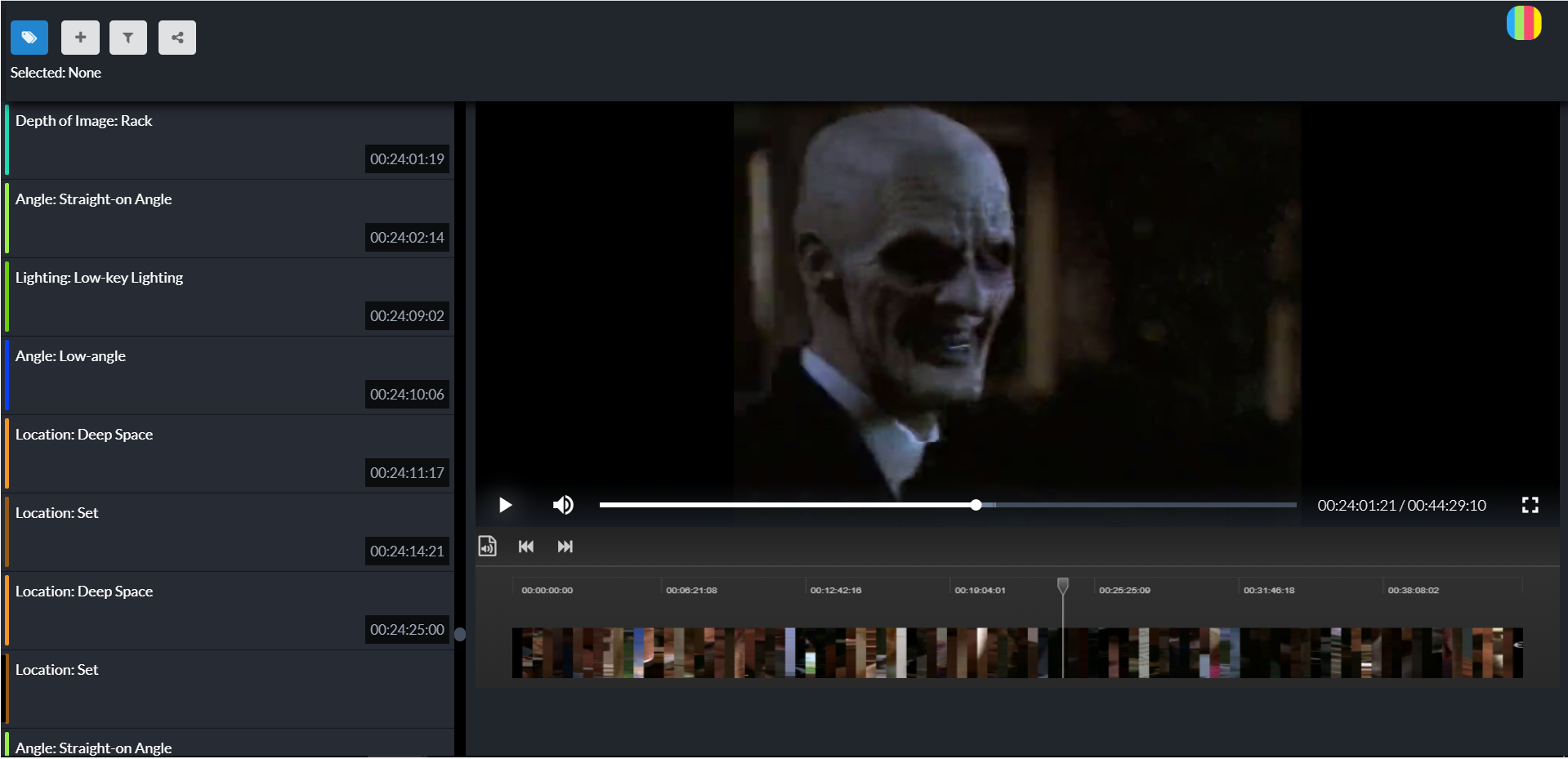

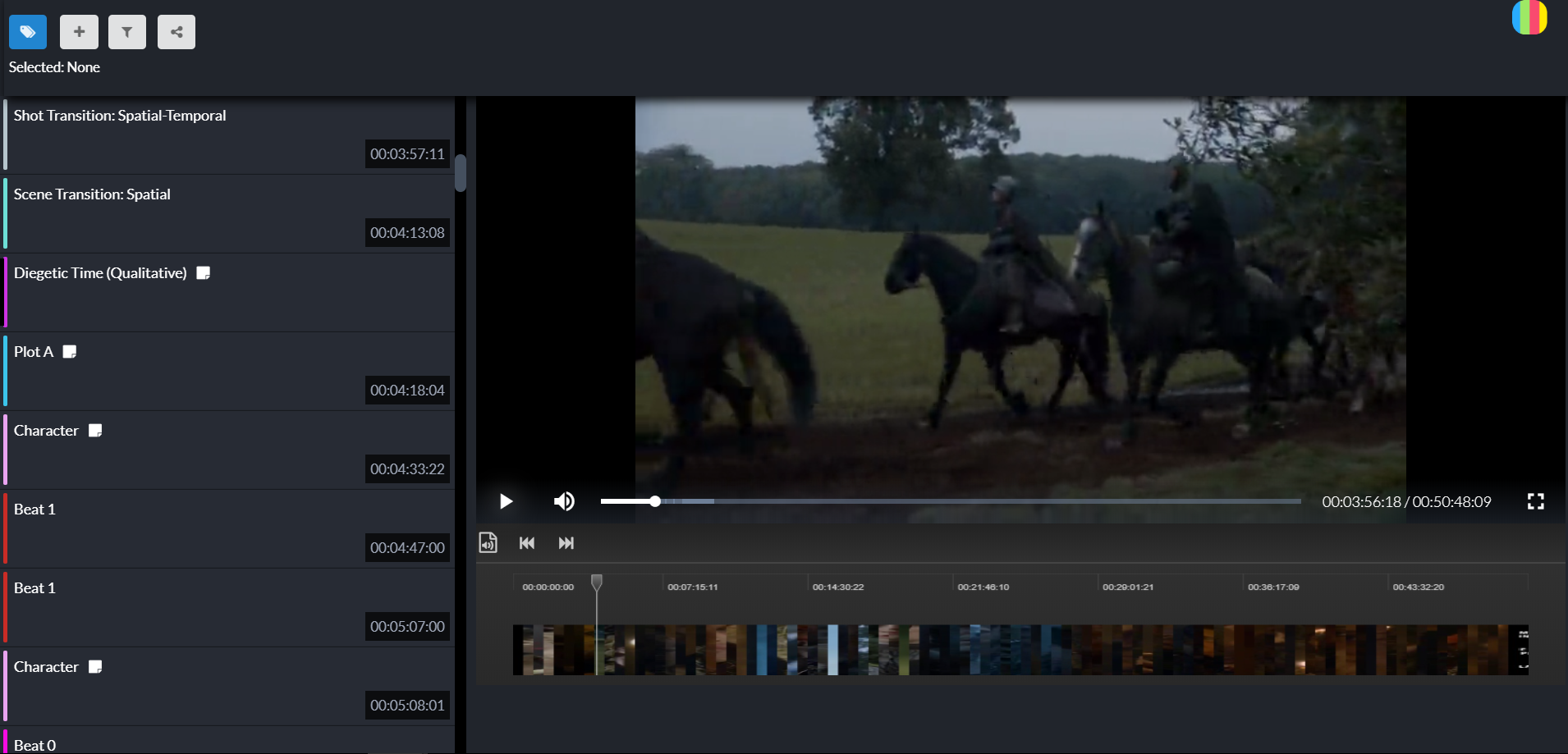

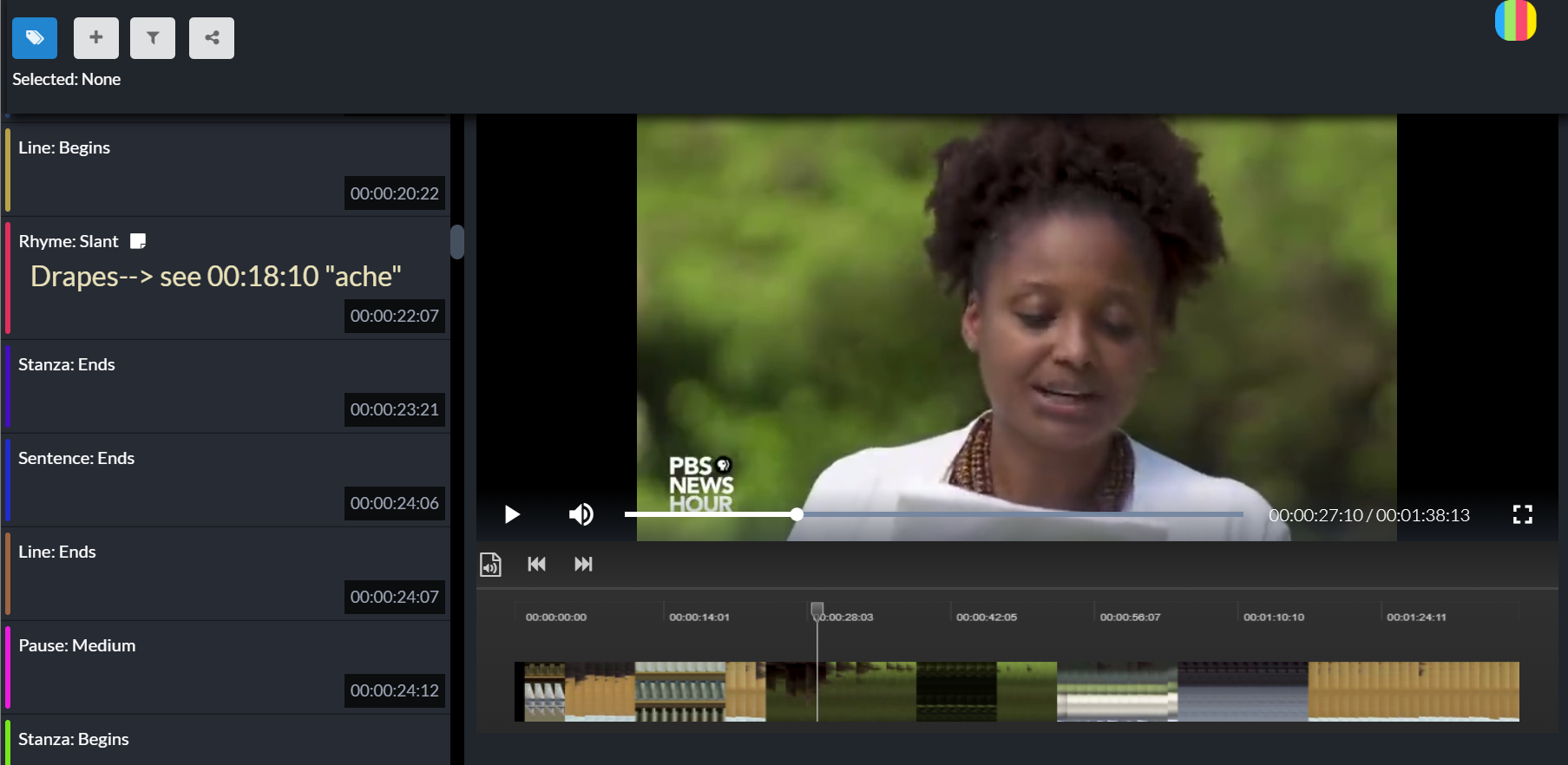

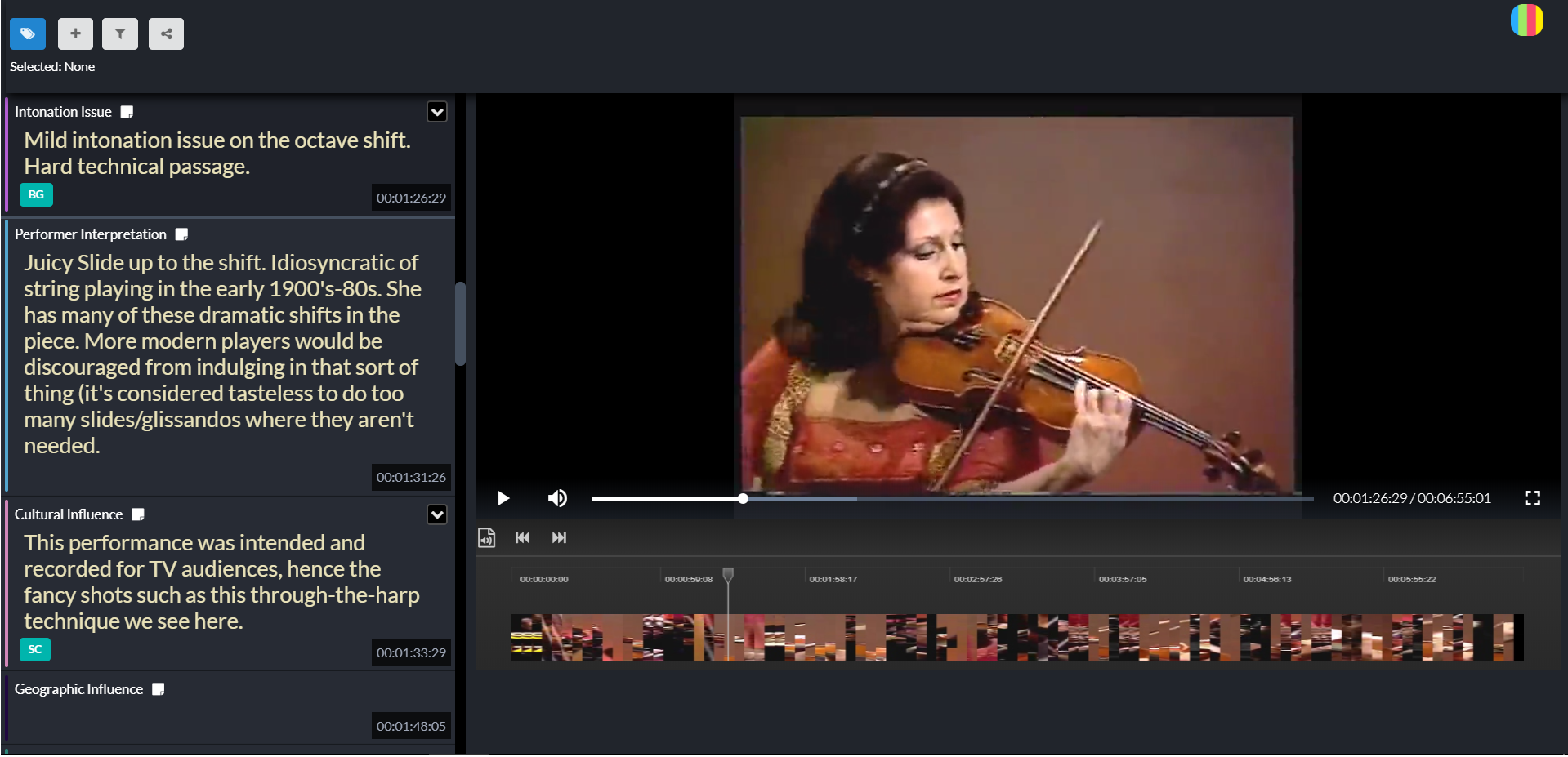

Selecting, for example, I Love Lucy, the user enters the Annotation

Interface. Here they can watch the media in an interface akin to familiar streaming

services, but with the addition of a vertical column of time coded annotations that

scroll

as the media plays.

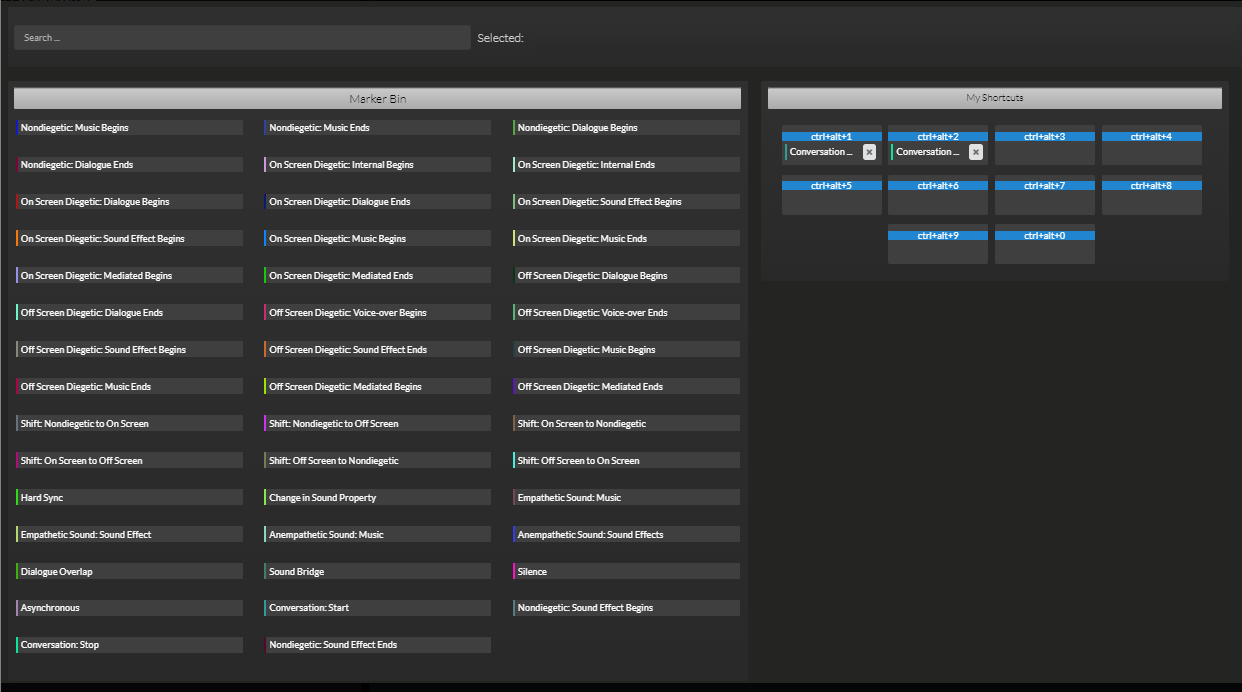

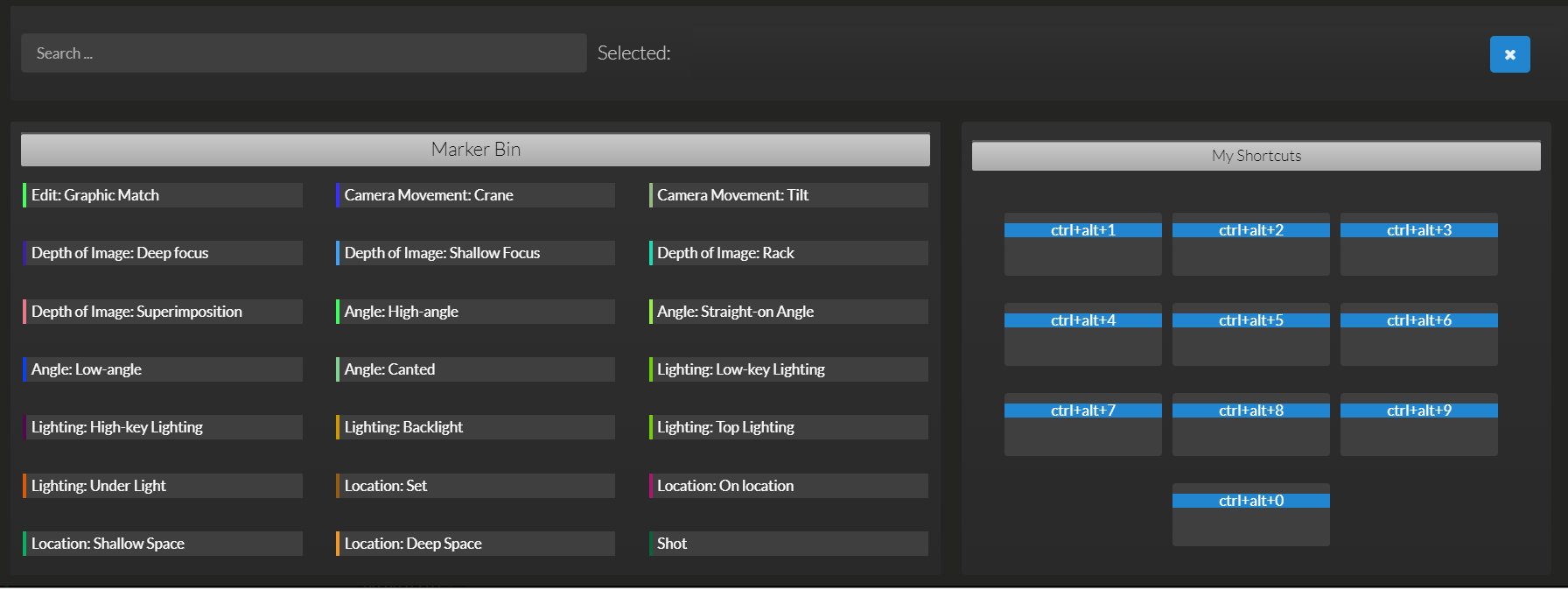

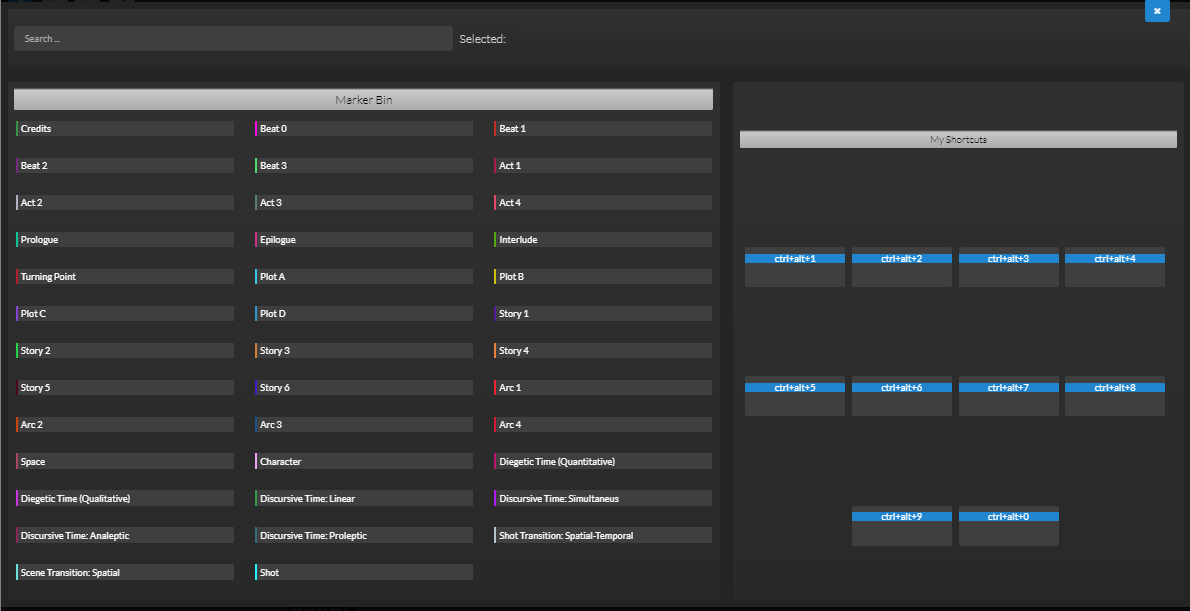

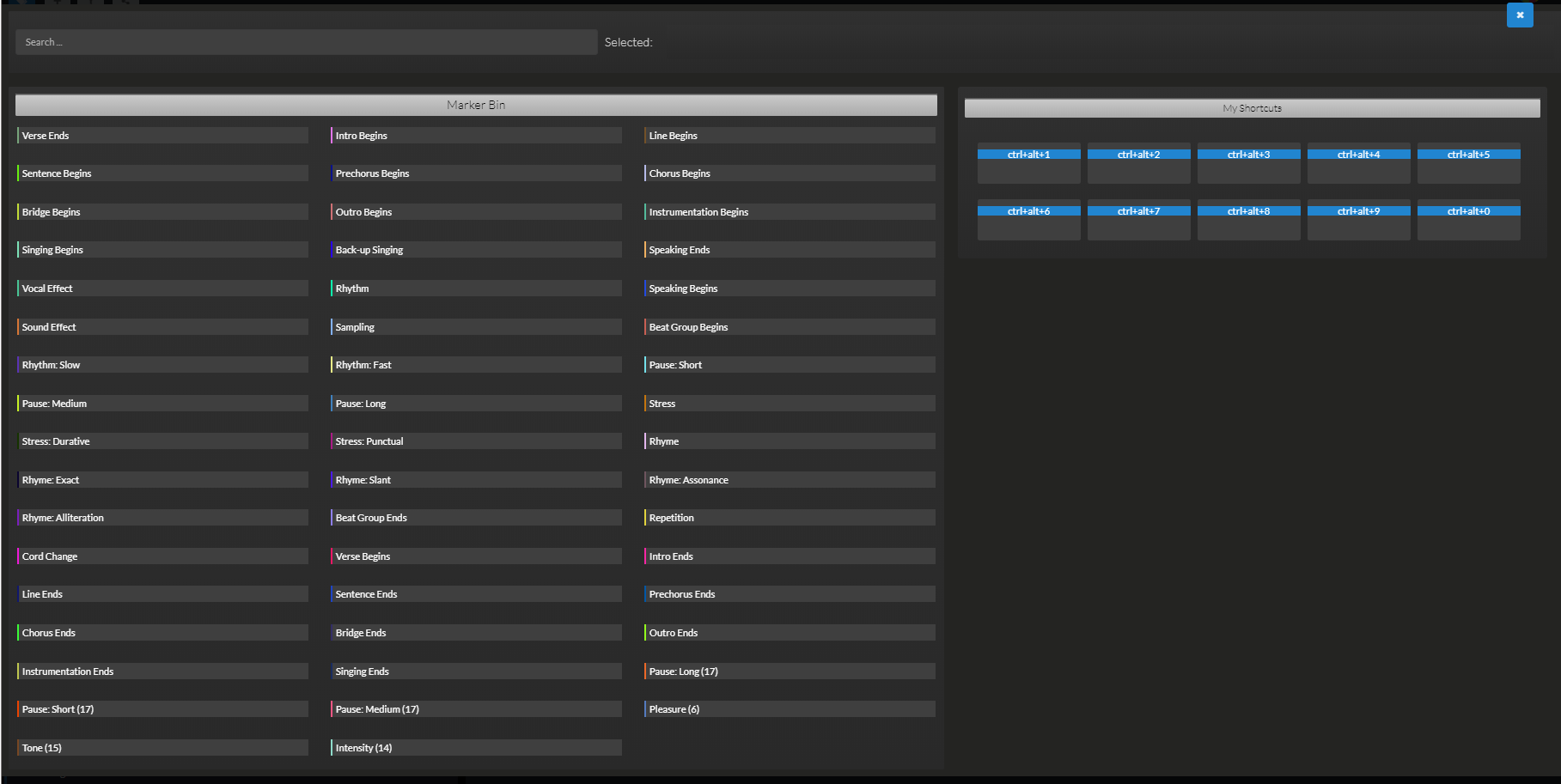

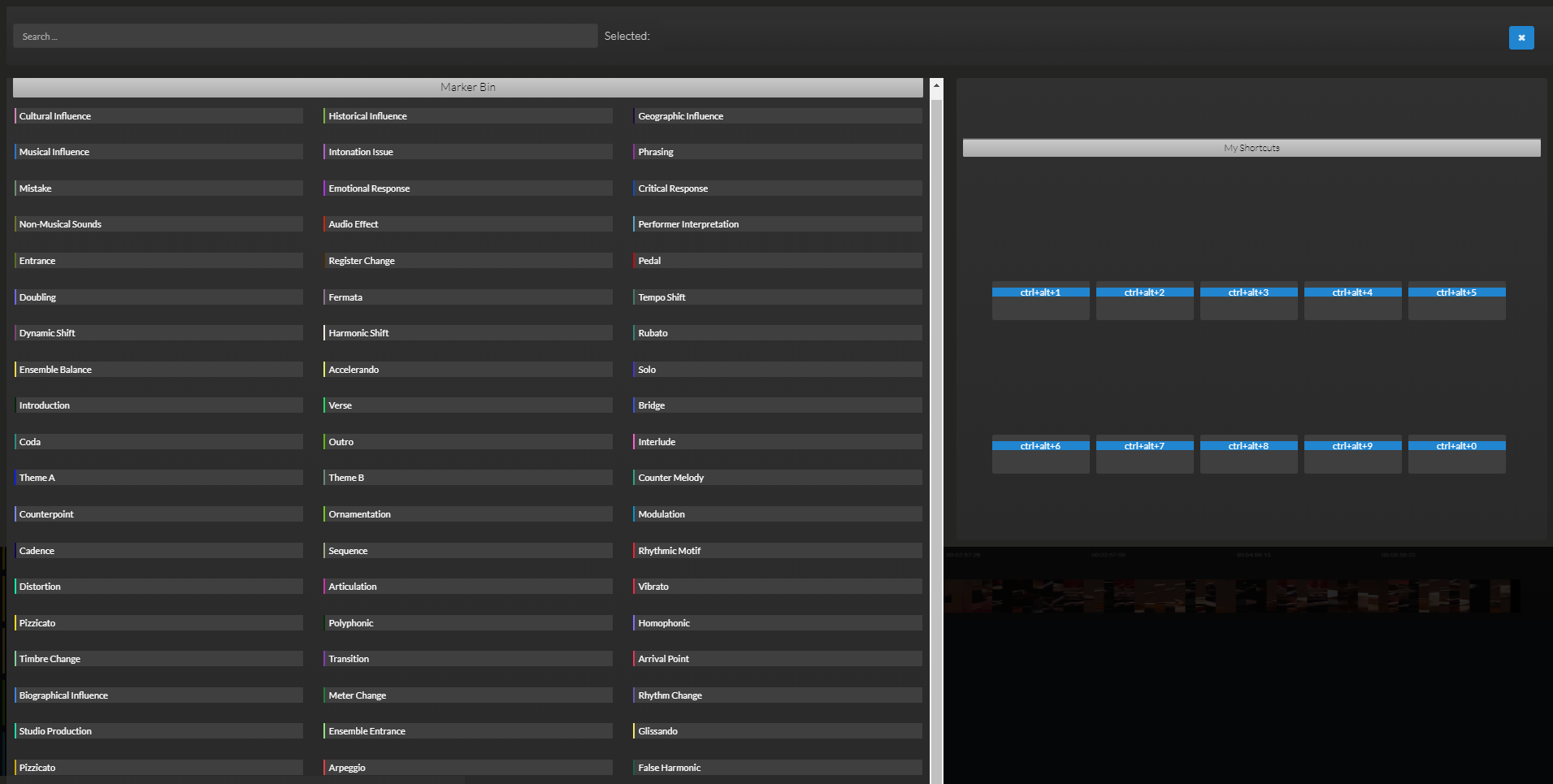

Clicking on the blue marker button in the upper left-hand corner reveals the Schema

Pane.

Here, users select markers and set short-cuts, which enables the marking process once

the

user returns to the Annotation Interface. This process can take weeks, especially

if a

group is marking across multiple objects. The repetitive work of collaborative marking

not

only helps students comprehend the forms they are analyzing, but also reveals the

necessary judgments involved in deciding how and when to mark. As a result, it emerges

that each marker and the concepts it represents become legible as a formal construct

instead of a natural given.

At a high level of frequency across seven years and twelve classes, Armoskaite, Burges,

and Mueller have observed that

Mediate encourages a process of learning that

slows down the rapid-fire consumption of everyday media, upending the seemingly intuitive

and immediate dimensions of the audiovisual field.

[2] Recursive and reflexive, digital

annotation in

Mediate has made our students tune into the audiovisualities

that construct them as seeing and hearing subjects through a range of material forms

that

operate in different cultural contexts and with differing social functions. The digital

annotation in

Mediate align with what Liliana Melgar Estrada et al. [

Melgar et al. 2017] conclude is "the most significant methodological impact" of using

ELAN and NVivo: "making the analytic procedures more explicit," can generate "more

self-reflection about scholarly work." The authors suggest that digital annotation's

greatest strength is its reflexive ability to draw users' attention to various units

of

analysis that they might not otherwise notice. Similarly,

Mediate allows

users to slowly comprehend what makes a film or poem or composition what it is as

a

mediated genre unto itself, but also to grasp how this medium-specificity turns on

"units

of analysis" [

Melgar et al. 2017] that are subjectively chosen in the first place.

Just as all data are capta [

Drucker 2011], the unit of analysis by which a

datum is captured when digitally annotating audiovisual media is itself invented.

The

invented dimension of these units are revealed whenever students discuss and debate

marker

definitions, as we have seen in all of our classes.

The collaborative process of digital annotation enabled by

Mediate, starts

to address one of the concerns raised by Melgar et al. in their analysis of the current

state of digital annotation: that more "collaborative" and "systematic" efforts might

allow scholars to transcend "small scale" analyses easily replicated on paper [

Melgar et al. 2017]. In this, they acknowledge what has long been a both celebrated

and critiqued feature of the digital humanities: its problematically neoliberal stress

on

teamwork that we hope might be rescued as a project of collective reading and

collaborative curriculum [

Burges et al. 2016]

[

Sebok 2014]. Significant as the debate over the political economy and

research efficacy of the digital humanities is [

Allington et al. 2016]

[

Da 2019a]

[

Da 2019b], we nonetheless want to stress that in our courses we have found

that scaling up — collectivizing and collaborating on digital annotation through groups

of

students producing and sharing data with one another about audiovisual media — has

allowed

those students to arrive at analytic findings that go beyond what they are able or

willing

to do otherwise.

To arrive here, we must not assume that our students are "digital natives" who are

naturally better at studying and thinking with computational devices than with pen

and

paper. None of us believes this lazy assumption; some of us actively work against

it in

our classes. As we will show, we have nonetheless seen outcomes that are educationally

remarkable, especially due to the collaborative learning that Mediate

enables, when it comes to how digital annotation in Mediate fuels our

students' grasp of a range of audiovisual media in medium-specific ways. Often such

medium-specificity is tethered to the discipline-specific approaches that we use in

our

courses, as we chart in the next section. But something interdisciplinary has arisen

across our courses too: the cross-disciplinary concept of audiovisualities that this

essay

advances.

Three Disciplinary Case Studies in Digital Annotation

In our courses, we position individual mediums as possessing unique material forms

that

exist in cultural contexts and have some social function, as is reflected in our schemas.

These schemas emerge from discipline-specific frameworks, with some of us stressing

material form, cultural context, or social function more when teaching with

Mediate. In this section we provide three case studies. The first draws on

a number of film and media studies classes where Burges wanted students to understand

how

a range of audiovisual media — television, poetry, and pop songs in the two cases

discussed here — work formally such that they can be materially differentiated from

another medium, even if they share certain properties. While Mueller and Armoskaite

share

this concern to varying degrees, their expertise has driven them to underscore questions

of cultural context and social function more prominently in the study of audiovisual

media. In his history class for music majors, Mueller asks students to interpret how

a

range of historical contingencies influences the creation and performance of specific

musical sounds. Here, Mediate is a prompt to redirect assumptions about music

that students already think they "know." Bringing together questions of material form

and

cultural context, Armoskaite uses Mediate to spark students to delve into how

language in advertising itself is audiovisual — or more precisely, how language has

a

social function in commercial media that turns on how it activates the interplay of

hearing and seeing vis-à-vis linguistic and discursive content meant to induce an

action

in someone.

Case Study 1: Material Form in Film and Media Studies (Burges)

Questions of material form are central in the film and media studies classes I teach

for the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering at the University of Rochester,

including the two I discuss here: "The Poetics of Television" and "Introduction to

Media

Studies". In "The Poetics of Television", for example, we spend significant time

studying the different ways in which the episode is a form of inscription that organizes

the audiovisual experience of television in narratively open and closed ways. In

"Introduction to Media Studies," we discuss television not only from this narrative

perspective, but also from the perspective of television as a historically variable

technology for transmitting sounds and images onto a screen that was, for many decades,

primarily part of the TV set. These are both material to the form of television, with

the latter especially providing the specific audiovisual means by which television

mediates and materializes narrative, information, and advertising for its viewers.

In my

classes, the question of material form — of how a medium is a matter of form — is

not

reducible to solely inquiring into these means in order to secure that which is, to

recall Clement Greenberg [

Greenberg 1960], irreducibly exclusive to it. It

instead involves pursuing lines of inquiry with students in which we explore the

specificity of a range of media — from television and film to poetry and song — through

the shifting constellations of qualities constrained and enabled by diverse audiovisual

means in the first place [

Doane 2007].

Digital annotation in Mediate indelibly contributes to this pursuit,

especially through the schemas that provide the basis of the highly collaborative

— as

we will show — marking that students do over the course of a semester in classes such

as

"The Poetics of Television" and "Introduction to Media Studies." The schemas we have

designed so far try to capture the constellations of qualities that make up any medium

one might annotate in Mediate. In "The Poetics of Television," the schemas

were designed around aural, visual, and narrative qualities in order to show how sound,

image, and story are respectively constructed on TV.

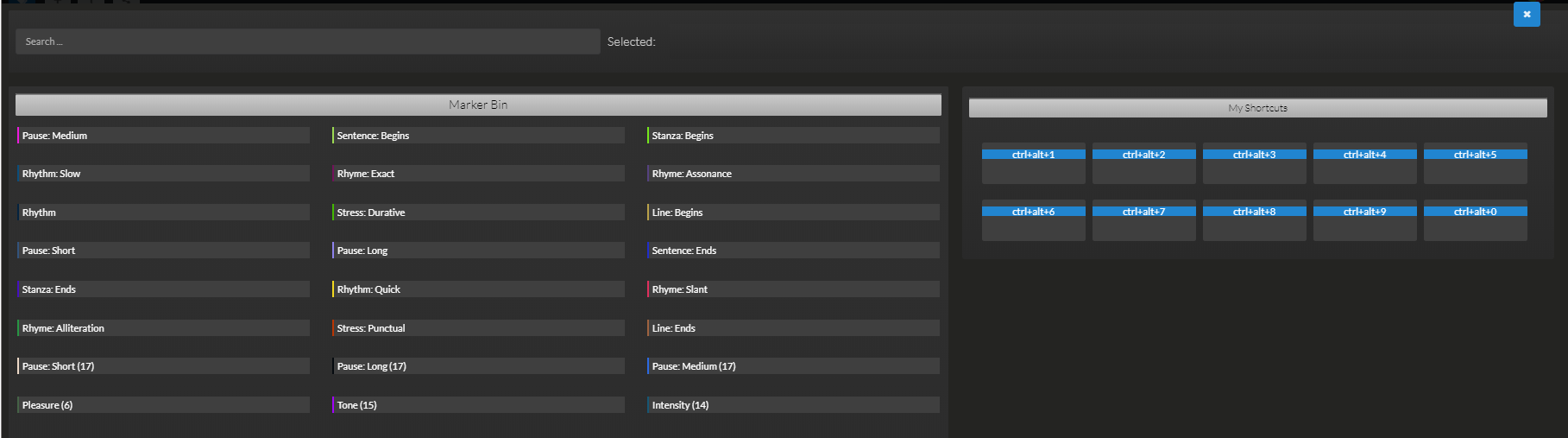

The schemas for "Introduction to Media Studies," were designed with comparison in

mind,

so one focused on a set of markers for annotating poems read aloud by their authors,

the

other on a set of markers for annotating pop songs by individual singers and bands.

Over the course of a semester, students in these two classes worked collaboratively

in

groups of four to six people to annotate on the basis of the schema or schemas that

group was assigned, building toward long papers in which they explored a wide range

of

topics through distant and close readings performed in writing and through

visualizations. Regardless of the topic, these papers almost universally exhibited

a

deep knowledge of the material form of the audiovisual medium under study; the specific

interplay of sight and sound embodied by TV, for instance, became "second nature"

to one

student, "so much so that when I watch TV now I automatically mark the episode in

the

back of my mind" [

Crumrine et al. 2016]. This is the result of what the students

characterize as the "immersive" dimension of

Mediate in which time spent

marking, however "irritating" and "monotonous" and "tedious" in its slowness over

the

semester, generates a profound concept of the qualities that give material form to

their

audiovisual experience [

Allen et al. 2016]. This is most palpable when one looks

more closely at final projects students completed, in which their collaborative efforts

yielded a remarkable level of quantitative data and qualitative observation worth

understanding in greater nuance.

[3]In an essay for "The Poetics of Television" entitled "The Formal Nucleus of Television,

and Its Subservience to Narrative" [

Allen et al. 2016], the students argued that

dialogue is a key element of the "formal nucleus" of TV by exploring the nexus of

sound

and story in four historically and generically variable series defined by open narration

(

Game of Thrones,

Dark Shadows,

Guiding Light,

and

Robotech). On the basis of hundreds of markers the students in this

group annotated, they argue that dialogue is an elementally generative feature of

the

"aural design" of television that "advance[s] the narrative progression of an episode."

This is due to dialogue allowing "all details pertinent to the comprehension of the

narrative, in terms of both plot and character, to be enumerated in explicit,

unequivocal, and economical terms." This group further contends that the television

camera often obeys the human voice, suggesting that visual design flows from aural

design, for instance, on the basis of the 54 on-offscreen and off-onscreen shifts

of

sound vis-à-vis the image and diegesis that the group marked in the infamous Red Wedding

scene of

Game of Thrones while annotating in the Aural Schema. While both

the visible and the audible are subservient to narrative in the argument this group's

paper makes, it nonetheless richly charts the interplay of sight and sound within

storytelling on TV, revealing how that mediated interplay — that audiovisuality —

lets

narrative take material form on screen.

"Introduction to Media Studies" similarly attuned students to material form. But rather

than focusing on one audiovisual medium to achieve this end, as in "The Poetics of

Television," I used a comparative approach in which I asked students to work in groups

to annotate poetry and pop songs to which they listened closely and repeatedly in

Mediate. Students were not allowed to pull print versions of the poems

they were annotating on the basis of oral renditions by their authors, forcing them

to

use their ears to grasp the differences between poems and songs marked using schemas

developed for each of these genres. What one group observed about those differences

will

sound obvious: while rhythmically structured and lineated language is the medium of

poetry, pop songs are much more musical in their means, depending on instrumentation,

chord progression, beat groupings and so on [

Colberg et al. 2019].

But what is less obvious is how the students in this group came to experience this

difference because Mediate introduced annotation into audition. In

annotating, they heard what was material to the form of poetry and pop

songs as a fixed and motivated structure of aural notation. The songs went from being

an

internal experience of sound and music to appearing as an externalized — because now

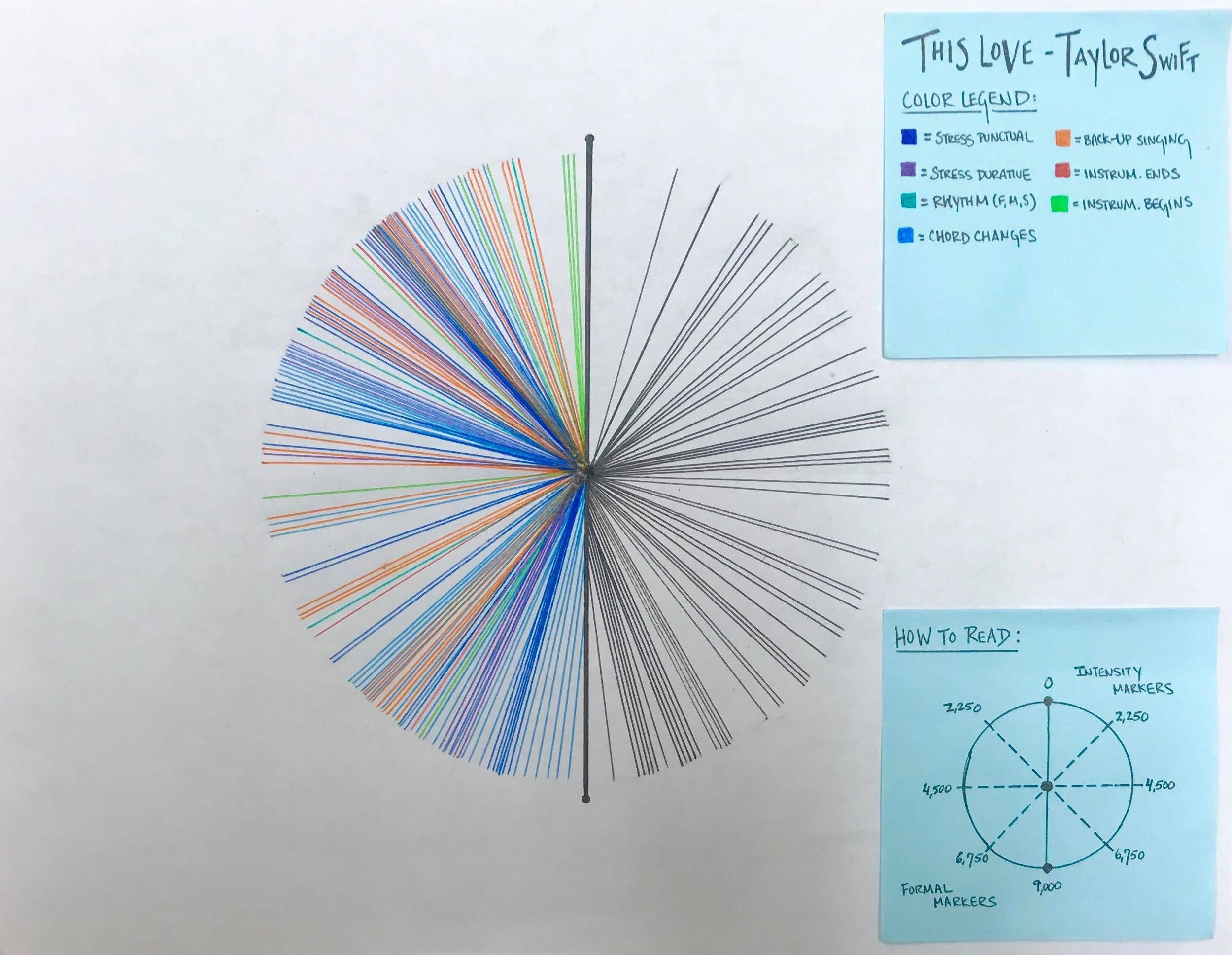

annotated — form of audiovisual inscription. Thus the long paper this group produced

focused less on material form in favor of trying to pinpoint what constellation of

audible qualities inscribe what they call "intensity." For this group, intensity refers

to how "affective response" and "aesthetic emotion" in a mediated genre of sound turns

upon medium-specific features, as in their LP record player-inspired visualizations

of

two songs, Troye Sivan's "Wild" and Taylor Swift's "This Love." Audiovisualities in

their own right, these experimental data visualizations show how distinct kinds of

vocal

stress, chord changes, back-up singing, and instrumentation not only mark the form

of

these songs, but also form the possibility of having a musically "intense" reaction

to

them as well.

In classes such as "The Poetics of Television" and "Introduction to Media Studies,"

digital annotation in

Mediate enables students to work together to see and

hear the material form of a range of audiovisual media. It is important that they

are

working together, collaborating to annotate such that both within and across their

groups they are able to explore audiovisuality in a collective way that has both

quantitative and qualitative effects. On the one hand, the quantitative dimension

of

their collaborative efforts is visible in the plenitude of markers that each group

generates as a working collective, and in how they draw on the audiovisual data produced

by other groups marking in the same class to understand the annotation that has occurred

in a given group. On the other hand, the repeated marking required to yield thousands

of

data points they can share with one another engenders a quality of description and

interpretation that shows how close they understand the material forms of film,

television, poetry, and pop songs from multiple audiovisual angles of seeing and

hearing. As we have more fully argued elsewhere [

Burges et al. 2016], however,

that "truth" depends upon the discussions that often emerge over how to collectively

define and collaboratively mark a unit of analysis within and across groups as they

annotate features of material form; these discussions over how to see and hear, though,

only further shore up both that no medium is a natural given, and that every audiovisual

experience is mediated.

Case Study 2: The Cultural Contexts of Music History (Mueller)

Although connected institutionally, Eastman School of Music (ESM) is quite different

from the rest of the university in terms of its student population, educational goals,

and curriculum. All of ESM's approximately 500 undergraduate students are music majors,

with a primary focus on Western classical music.

[4] Our students are some of

the best young musicians in the world, meaning that most view their classroom activities

through the lens of their future careers in performance, composition, and pedagogy.

To

even gain admittance, they need to have remarkable expertise and years of specialized

training in a tradition built around individual composers and master performers. So,

while these students bring a strong passion for music into the classroom, doing academic

work often forces them to confront viewpoints and approaches that are frequently taken

as natural rather than culturally constructed.

Most of the traditions represented at ESM are heavily reliant on musical notation,

a

highly advanced system of written symbols that has, over many centuries, enabled the

development and circulation of music that originated in Western Europe. In many

respects, the very presence of notation constitutes the tradition [

Taruskin 2005]. Musical notation can also be understood as a form of

audiovisual inscription that communicates specific information about both how to perform

music and also how an individual piece functions melodically, harmonically,

rhythmically, and formally [

Moseley 2015]

[

Rehding et al. 2017]

[

Kittler 1999]. Reading music, as we would say, is a presumed skill that

students rely upon as they move through the robust series of classes in music theory

and

history, both of which differently emphasize score-based analysis of internal (within

a

piece) and external (within a tradition) musical features. As a result, students are

very comfortable working with written music, as well as the specialized language used

to

describe it. Still, the culture surrounding classical music has calcified certain

perspectives, especially on what it means to do analysis. For many students, music

analysis is too often conceived of as an action solely in visual terms, rather than

an

act that takes place in a far more expanded audiovisual realm.

In Fall 2019, I introduced Mediate into my "Experiments at the Edges of

20th Century Music," a required course within the undergraduate music history core.

My

goal was to foreground listening, rather than reading, as the primary means of analysis.

As exceptional performers already, my students listen with an expertly attuned

understanding of musical performance. But while they continually analyze music while

listening, they do not always listen historically — that is, attend to how specific

musical moments express historically contingent beliefs about culture, society, or

the

many processes of music making. There is no inherent problem with their modality of

listening. However, it is not always congruous with my major pedagogical goal: to

examine and interpret how music and its written tradition are both heavily mediated

creations, dependent on historically situated actors with different investments and

values. By asking students to pay attention differently, Mediate not only

foregrounds listening but also asks students to translate that listening into specific

observations represented visually. In effect, this reverses the standard audiovisual

direction of music making. Rather than move from visual inscription (notation) to

aural

expression (performance), Mediate renders what is heard into specific

visual markings of that performance. Unsettling the assumed relationships between

the

visual and the aural — by putting listening first — encourages alternative viewpoints

to

come into the forefront of the analytical process.

Inspired by previous uses of Mediate in the classroom, I had students

complete a semester-long collective analysis project. Our work began before I introduced

the Mediate platform by continually asking students during class

discussions and daily responses to listen through a series of five interrelated

questions oriented towards cultural contexts:

-

Who or what shaped this particular music or performance?

-

What would it be like to perform this music?

-

What are the musical materials used in the creation of this piece?

-

How does this musical material transform?

-

What do you think the creators were trying to say or accomplish with this

music?

[5]

For their Mediate project, students organized into groups of two to four.

Each student within those groups picked one or more of these questions and marked

up

their audio in Mediate from those perspectives. I developed specific

markers for each question to aid in this process, but also encouraged students to

develop others to meet their specific needs.

As they listened, students would mark everything from the seemingly obvious — what

they

might otherwise notice without thinking — to those details obscured by the rapid

unfolding of any time-based art. After creating several hundred markers, each group

began to decipher their efforts and develop a thesis for their written analysis with

the

same five questions again providing a road map. The class went through this process

in

two different iterations. First, all groups analyzed the first movement of William

Grant

Still's Symphony No. 1. Then, each group picked a piece of music or specific performance

from a given list of artists and composers.

Two general observations emerged out of the individual reflections written at the

end

of the semester. First, the slow, sometimes-tedious markup process requires active

listening. Many students discussed how they came to notice subtle details and

complexities precisely because the marking up process made "passive" or "casual"

listening impossible. The intensity involved with repeated listening did not always

change their initial opinions, but rather increased the precision and specificity

of

their observations. One student remarked with surprise about "how much could happen

within one tiny second." Second, the processes of collective listening encouraged

individuals to consider multiple vantage points. Collaboration through group work

is not

always smooth or easy, and it is sometimes unpopular. But by learning from or being

challenged by their colleagues — perhaps even by becoming a "cultural context" in

miniature — many students reported that the dialogic experience enabled them to make

connections that were perhaps not obvious to them before.

The written work of each group also proved how valuable doing analysis away from the

score could be. Many groups wrote about meaningful moments that would have otherwise

remained hidden by only looking at the written notation — the particular use of vibrato,

the background noise in a recording, a reoccurring timbre, or the use of space or

a

particular texture in the orchestration. Through the analysis of seemingly discrete

details in relation to the background of the composer or other cultural influences,

students then found ways to relate what happens musically to what that performance

might

mean more broadly, which is to say historically. As one student commented, the analysis

provided a way to understand how music functioned as an interconnected web of historical

events, musical influences, and experiences of "real life people." In comparison with

previous semesters, the written work of the students in this class was at once more

precise and bolder in their conclusions.

The slow and collective process of listening through Mediate allows

students to re-situate their otherwise expert ears towards music as a form of

audiovisual inscription. Music is a time-based art that exists in performance, yet

it

nevertheless remains heavily dependent on the visual realm. The specialized language

used in traditional forms of analysis — a Neapolitan sixth chord, for one example

—

describes both what music sounds and looks like. As a digital platform that creates

a

method for analysis, Mediate makes the audiovisualities of music clear.

Musical culture is and has always been an audiovisual culture as well, and new

possibilities surface for students about this fact when they experience music through

Mediate.

Case Study 3: Social Function in Linguistics (Armoskaite)

The Department of Linguistics in the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering at

the

University of Rochester, while a part of the social sciences, is a hub of

interdisciplinary research with ties to other departments, including Music (with a

focus

on perception and production of sounds), Brain and Cognitive Science (with a focus

on

meaning and language processing), Anthropology (with focus on culture and language

intersections), and Psychology (with a focus of child language acquisition). As a

field,

linguistics covers a vast number of topics and methodologies, hence it is impossible

to

provide a general description that would fit the range. For the purposes of this case

study, it will suffice to state (i) that linguistics focuses on of the makeup of

grammar, which is a set of sub-systems of sound, form and meaning; (ii) and that these

subsystems are used for communication, a function that interacts with social conventions

and societal values, a.o. [

Fasold and Connor-Linton 2014].

My course "Language and Advertising," requires students to consider language use in

the

context of audiovisual marketing against the backdrop of current social trends. While

Linguistics does not have a Business or Marketing track, the course routinely is taken

by business majors and consistently is a popular elective among other non-Linguistics

majors. I face a diverse group of students with different backgrounds, skills, and

assumptions, though united by the three common denominators. First, the ubiquity of

advertising in their lives gives them a false sense of familiarity and assumed knowledge

of the medium; second, they want to learn the nuts and bolts of the advertising machine;

and third, they possess limited knowledge of linguistics. Over the course of the

semester, they learn that the social function of language in advertising is to

manipulate, with commercial media, working to apply psychological pressure through

a

mode of audiovisuality that depends on influencing our emotions and circumventing

our

rational mind, a.o. [

Sedivy and Carlson 2011]

[

Lewis 2013]

[

Poels and Dewitte 2006].

Situating a familiar medium — advertising — within a likely unfamiliar field —

linguistics — necessarily slows down the students. They learn to analyze the linguistic

components that, to call back to the film and media studies case above, "make" the

medium. The material form that interests a linguist, however, includes not only sounds

and images of the kind that interest Burges and Mueller in their courses, but also

the

very structure of language as humans speak, read, and hear it. For example, each of

the

following posters can be deciphered in the linguistic terms of sound, form, and meaning,

which shows that even print advertising functions as an audiovisual medium.

The American Red Cross "Missing Types" campaign (2018) presents a sound-based

puzzle for the viewer to acoustically fill in, whether in silence or out loud: all

the

missing elements are vowels. The viewer goes in search of those vowels, enjoying a

language game that depends on visual absence engendering audio presence. And because

the

vowels are associated with types of blood, this audiovisual play becomes a linguistic

mechanism for soliciting blood donations.

The

Snickers "Satisfectellent" (TBWA 2007) advertisement plays upon another element

of grammar, namely, derivation of words. In this case, a word that is possible, but

does

not exist, is created. The novelty of the coined word is the striking — and strikingly

audiovisual — feature of the advertisement: the joy of recognition of the brand of

the

snack is fused with the unexpectedness of the word.

Finally, the

Greenpeace "Straws Suck: Gull" (Rethink 2018) advertisement exploits the shades

of meaning of the verb "to suck." The painful visual is certainly not the first

association we have about sucking through straws, which we may think about in sonic

and/or tactile terms primarily. But the unexpected visual connotation is meant to

shock

us into changing our habits of consumption.

However, language in print advertising engenders audiovisual experience in a far more

static way than the advertising that flows across our many screens as moving images

and

dynamic sounds. The latter contains hundreds of speech patterns in addition to

innumerable cues for our ears and eyes. Superimposed on moving images, these patterns

and cues come at a viewer at a speed that barely allows them to register the component

parts, let alone perform a thorough analysis. Mediate creates a space for

such analysis external to the ephemerally immediate modes in which we normally consume

commercial media. In so doing, it makes legible that language plays a constitutive

part

in the interplay of sight and hearing — that all three of these human abilities

contribute to the social function of manipulation that is the raison d'etre of often

brilliant acts of commodified audiovisuality that want us to buy or buy into something.

Mediate gets students to treat the audiovisuality of advertising as a

constellation of elements variously linguistic, optical, and aural — as an object

of

analysis.

This takes time over the course of the semester. In "Language and Advertising" (Fall

2018 and Fall 2019), I spent three weeks teaching students the fundamentals of

linguistics using similar examples to the print advertisements discussed above. Building

on this print unit, we then turned to the challenge of analyzing commercials using

Mediate. The students began by analyzing an ad without the use of

Mediate. Then I modeled the slow and detailed analysis conducted through

Mediate by providing them with samples of my own marked-up commercial. We

discussed their observations, along with my own, which gently lets them understand

how

many details they've missed in their own observations. The students were then trained

on

the platform and introduced to the schema over two class sessions. After that initial

introduction, the students took charge of their own learning with only a light editorial

supervision.

Circumventing the top-down didacticism of the traditional lecture, Mediate

allowed the students to immerse themselves into the material on their own. Working

in

groups, they were tasked with selecting and analyzing at least two video ads, splitting

up the work of marking (what we call "coding" in the field of linguistics) amongst

themselves. Rather than a traditional linguistic analysis of a video ad that might

include a transcription of the text divorced from the audio and visual cues,

Mediate facilitated a holistic approach to the interplay and

interdependencies of the audiovisualities commercial media employ.

In slowing down their observations, they are forced to think about each element in

the

totality of the advertisement such that it emerges as a linguistic object of audiovisual

analysis, with the manipulative properties of this object becoming ever clearer as

its

social function over the time they spend in Mediate. As one student noted,

"there is no escape but to analyze." At the end of the semester, the groups presented

their analyses of commercial media, with the entire class responding. This collective

response included debates over how each group defined certain linguistic, audio, and

visual units of analysis, and about the conclusions about manipulation in commercial

media that each group reached. These discussions — aided by the carefully coded examples

in Mediate — were paramount in helping students build an applied

understanding of the social function of advertising from an audiovisual angle grounded

in linguistics as an interdisciplinary field.

Despite their engagement and increased capacity with audiovisual analysis through

Mediate, there still is room for greater interdisciplinary collaboration

in "Language and Advertising", especially in light of the cross-disciplinary sense

of

audiovisuality we are advancing in this article. In my course, I welcome film experts

as

occasional invited speakers. But through my discussions with Burges and Mueller, I

have

realized that more sophisticated ways of tuning into the linguistic, visual, and sonic

patterns would offer further opportunities to explore the range and means of consumer

manipulation. For example, thus far, I have left out musical aspects completely as

I

lack relevant training. In the future iterations of this course, I think about the

potential for more nuanced analysis if I could harness Mueller's expertise in helping

students define the auditory components, if Burges could work with students to delve

further into the visual form — that is, if students benefitted not only from their

collective defining through marking, but also the collective expertise of a more

intentionally cross-disciplinary approach to teaching and research.

Audiovisualities out of Annotation

Across our individual classes, we have seen our students more fully enter the study

of

audiovisual media as they are defined by material form, cultural context, and social

function within our respective disciplinary frameworks. In sharing these experiences

with

one another across our disciplines, we have been reminded that, when it comes to the

audiovisual field, a film and media studies scholar should sometimes see and hear

that

field

like a music historian who should sometimes see and hear it

like a linguist. In noticing that we should see and hear like each other

more, even as we explored medium-specific matters with our students, we have arrived

at

the cross-disciplinary concept of audiovisualities. Pedagogically and intellectually

segregated from another due to the division of labor that organizes the modern research

university, this concept allows us to think about the interplay of sight and sound

more

promiscuously and productively, overcoming the binaries that too often divide the

audible

and the visual and the divides that splinter disciplines from one another institutionally.

In working together the last few years on digital annotation, we have learned to think

more comprehensively across our respective fields about the (re)mediated sites where

the

physical and cultural operations of audiovisual experience converge. It is these locations

of convergence that construct not only sensory and social subjectivities grounded

in

seeing and hearing, but also material forms and collective technics that set the

conditions of possibility to see and hear to begin with — in short, that construct

a

manifold of audiovisualities. Our work on

Mediate has helped us to estrange,

even to alienate, the "natural order" that has been imposed on our experience of that

manifold, or what Michel Chion describes as the "audiovisual contract" [

Chion 1994, 9].

As this gesture to Chion telegraphs, we are not the first group of scholars to explore

such conditions. The cross-disciplinary concept of audiovisualities on which we have

landed already has a genealogy of thinkers — many of them cited at the outset of this

essay — associated with visual studies and sound studies, not to mention film and

media

studies, behind it. Indebted to them, we nonetheless think the practice of digital

annotation that Mediate provides contributes a collaborative model of

learning through collective reading that allows our students to conceptualize

audiovisualities beyond their individual selves (and our individual disciplines).

It may

do this, as well, for any scholars that take it up, especially, if not only in a

collective and collaborative form. The collectivity of digital annotation can take

that

which feels intuitive and internal and remake it as unfamiliar and external; the

collective act of exteriorizing that occurs in Mediate brings a new awareness

to the qualities and characteristics of a given audiovisual medium.

"History is nothing but exteriorities," writes Jonathan Sterne in

The Audible

Past, by which he means that we can only know the "sonic world" of the past

through its "efforts, expressions, and reactions" [

Sterne 2003].

Mediate embraces this point of view. Digital annotation in

Mediate asks students to exteriorize their reactions to audiovisual media

not only by slowing down their consumption of them, but also by turning what feels

subjectively intuitive, immediate, and internal (listening to and even playing music,

taking in a poem, consuming an advertisement, watching a TV show) into a mediated

object

to be analyzed collaboratively and collectively beyond oneself. Vivid examples of

this

process of exteriorizing abound in our case studies. In "Experiments at the Edges

of 20th

Century Music," students produce digital "notations," so to speak, through their use

of

Mediate, thus resituating the ocularcentric primacy of musical notation

through careful listening and historicizing. Similarly, in "Language and Advertising,"

the

interface renders commercials a constellation of elements that act on us linguistically,

visually, and musically in ways students can tangibly analyze. And the experimental

visualizations of two pop songs for "Introduction to Media Studies" draw on data produced

collectively through digital annotation about the aural experience of intensity to

visually represent the material form of that intensity.

Mediate therefore enables a defamiliarized perception of audiovisialities,

first and foremost, by challenging the consumption of media as an individual and discrete

act atomized from others. The work of collaborative annotation, which sets

Mediate apart from platforms such as ELAN and NVivo, reveals not only the

potential for different experiences of the same mediums, but that the criteria through

which we name and identify media — and indeed, our respective disciplines — can, and

perhaps should, be subject to the scrutiny made possible by collective re-examination.

Our

respective fields are built upon often now unspoken agreements about what constitutes

film

or poetry or music or television or advertising or language. Mediate shows

how "agreeing to disagree" on a given medium's properties remains a necessary move

within

and across disciplines, especially if we are to take into account critiques of both

collaboration and computation leveled at the digital humanities. The reverse of the

earlier claim, in other words, is also true. Our students often debate what a unit

analysis means when marking, mobilizing the differences amongst themselves in

collaborating on digital annotation. Similarly, when it comes to the cross-disciplinary

concept of audiovisualities, a film and media studies scholar should see and hear

the

interplay of sight unlike a music historian who should sometimes see and hear

it unlike a linguist as much as we should see and hear it like

each other.

The case studies recounted in this article reflect this collaborative process of

disagreement — the self-aware reflection upon "units of analysis" — as a pedagogically

necessary exercise in understanding the audiovisual world we inhabit in the present.

However, such a practice is not limited to the undergraduate classroom alone. The

collaborative nature of digital annotation breaks down a process that scholars, at

all

levels, often take for granted: the terms and tools through which we analyze media,

especially within our respective fields. By making us be both like and unlike each

other,

Mediate has allowed us to take hold of those terms and tools anew,

discovering audiovisualities out of annotation as a concept that unsettles what we

do with

the interplay of sight and sound inscribed everywhere into experience at present.

Works Cited

Allen et al. 2016 Allen, Joseph, Josh Barnes, Arielle Lin,

Mark Perilli, and Dean Smiros. “The Formal Nucleus of Television, and

Its Subservience to Narrative.”Unpublished essay, “The

Poetics of Television,”University of Rochester, Fall 2016.

Benjamin 1939 Benjamin, Walter. “The

Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.”In Benjamin, Walter.

Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, 4: 1938–1940. Edited by

Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Vol. 4. 4 vols. Selected Writings. Cambridge,

MA:

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006.

Bull 2013 Bull, Michael, ed. Sound

Studies: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. New York: Routledge,

2013.

Chion 1994 Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision: Sound On Screen. Translated by Claudia Gorbman. New York:

Columbia University Press, 1994.

Colberg et al. 2019 Colberg, Steven, Kayoung Kim, Hannah

O'Connor, and Rachel Yang. “Intensity in Songs: More than a

Feeling.”Unpublished essay, “Introduction to Media

Studies,”University of Rochester, Spring 2019.

Crumrine et al. 2016 Crumrine, Seth, Amber Hudson,

Simone Johnson, Sarah Kerecman, Anna Llewellyn, and Kyle Smith. “'That

sounds so melodramatic': Theatricality and Realism in the Soap Opera and Game of Thrones.”Unpublished essay, “The Poetics of Television,”University of Rochester, Fall 2016.

Da 2019b Da, Nan Z.

“The Computational

Case against Computational Literary Studies.”Critical

Inquiry 45, no. 3 (March 2019): 601–39.

https://doi.org/10.1086/702594.

Drucker 2011 Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.”Digital

Humanities Quarterly 5, no. 1 (2011): 1–21.

Fasold and Connor-Linton 2014 Fasold, Ralph W., and Jeff

Connor-Linton, eds. An Introduction to Language and

Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Foster 1988 Foster, Hal, ed. Vision

and Visuality. Seattle: Bay Press, 1988.

Greenberg 1960 Greenberg, Clement. “Modernist Painting.”In The Collected Essays and Criticism,

Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969, edited by John O'Brian.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Hansen 1992 Hansen, Miriam.

“Mass

Culture as Hieroglyphic Writing: Adorno, Derrida, Kracauer.”New German Critique, no. 56 (1992): 43–73.

https://doi.org/10.2307/488328.

Hansen 2004 Hansen, Miriam Bratu. “Room-for-Play: Benjamin's Gamble with Cinema.”October 109 (2004): 3–45.

Kittler 1999 Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Translated and with an introduction by Geoffrey

Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Lewis 2013 Lewis, David. The Brain

Sell: When Science Meets Shopping: How the New Mind Sciences and the Persuasion Industry

Are Reading Our Thoughts, Influencing Our Emotions and Stimulating Us to Shop.

London; Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2013.

Lingold et al. 2018 Lingold, Mary Catton, Darren Mueller,

and Whitney Anne Trettien, eds. Digital Sound Studies.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

McLuhan 1964 McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: New American Library,

1964.

Melgar et al. 2017 Melgar Estrada, Liliana, Eva Hielscher,

Marijn Koolen, Christian Gosvig Olesen, Julia Noordegraaf, and Jaap Blom. “Film Analysis as Annotation: Exploring Current Tools.”Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image

Archivists 17, no. 2 (2017): 40–70.

Moseley 2015 Moseley, Roger. “Digital

Analogies: The Keyboard as Field of Musical Play.” Journal

of the American Musicological Society 68, no. 1 (2015): 151-228.

Novak and Sakakeeny 2015 Novak, David, and Matt Sakakeeny,

eds. Keywords in Sound. Durham, NC: Duke University Press,

2015.

Pinch and Bijsterveld 2012 Trevor Pinch and Karin

Bijsterveld, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies. New

York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Poels and Dewitte 2006 Poels, Karolien, and Siegfried

Dewitte.

“How to Capture the Heart? Reviewing 20 Years of Emotion

Measurement in Advertising.”Journal of Advertising

Research 46, no. 1 (March 2006): 18–37.

https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060041.

Rehding et al. 2017 Rehding, Alexander, Gundula Kreuzer,

Peter McMurray, Sybille Krämer, and Roger Moseley; “Discrete/Continuous: Music and Media Theory after Kittler.”Journal of the American Musicological Society 1 April 2017; 70 (1): 221–256.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2017.70.1.221

Sedivy and Carlson 2011 Sedivy, Julie, and Greg N.

Carlson. Sold on Language: How Advertisers Talk to You and What This

Says About You. Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell,

2011.

Silverman 1988 Silverman, Kaja. The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema.

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Sterne 2003 Sterne, Jonathan. The

Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University

Press, 2003.

Sterne 2012 Sterne, Jonathan, ed. The

Sound Studies Reader. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Stiegler 2014 Stiegler, Bernard. Symbolic Misery, Volume 1: The Hyperindustrial Epoch. Translated by Barnaby

Norman. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2014.

Taruskin 2005 Taruskin, Richard. The Oxford History of Western Music. New York: Oxford University Press,

2005.

Zielinski 1999 Zielinski, Siegfried. Audiovisions: Cinema and Television as Entr'actes in History.

Translated by Gloria Custance. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999.

Zielinski 2006 Zielinski, Siegfried. Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archeology of Hearing and Seeing by

Technical Means. Translated by Gloria Custance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

2006.