In late fall 1965, John Kemeny wrote a 239-line BASIC program called

FTBALL***. Along with his colleague Thomas Kurtz and a few work-study

students at Dartmouth College, Kemeny had developed the BASIC programming

language and Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS), both of which went live

on May 1, 1964. BASIC and DTSS represented perhaps the earliest successful

attempt at “programming for all,” combining English-language

vocabulary (e.g., HELLO instead of LOGON), simple yet robust instructions, and

near-realtime access to a mainframe computer. Their efforts were funded by

the National Science Foundation and buoyed by their ingenuity and that of

undergraduates invested in the project. Beginning in 1966, Kemeny and Kurtz

rolled out an ambitious training course that, over the next few years,

taught about 80% of Dartmouth students and faculty how to program in BASIC

in just a couple of hours. From the mid-1960s on, they facilitated

connections to the Dartmouth computing network from local high schools and

other colleges, making the computer and BASIC accessible beyond

undergraduates at Dartmouth. Their free licensing of BASIC eventually led

to a splintering of hundreds of versions of the language by the 1970s and

‘80s, one of which was famously written by Bill Gates and Paul Allen and

helped to launch Microsoft, and another of which (less famously) introduced

me to programming on my Commodore 64 in 1982. My own introduction to

programming in the early 1980s was part of a larger movement of “computer

programming for all” in the 1980s, associated with computer

literacy campaigns and renewed emphases on educational technology in the

Cold War. But Kemeny and Kurtz got there first in the 1960s at

Dartmouth.

FTBALL is a great example of 1960s BASIC programming, but its cultural

significance is as a deliberate demonstration of computers as

fun. Preceded by games such as

Tennis for Two and

Spacewar!,

FTBALL was part of an approach to computing that ran counter to the more

dominant applications of defense and the hard sciences at the

time. FTBALL’s author, John Kemeny, was a math professor at Dartmouth, as

well as a former assistant to Albert Einstein at Princeton’s Institute for

Advanced Study and, later, President of Dartmouth College — a position in

which he led admissions for women and the recruitment of Native American

students. Along with his collaborator Thomas Kurtz, Kemeny believed

computers could be fun and should be widely accessible to a general

population of students. In the final report on an NSF grant Kemeny and

Kurtz received for their BASIC timesharing project, they write:

A remark is in order

concerning the use of computers to play games. They are a

magnificent means of recreation. But people feel that it is

frivolous to use these giants to play games. We do not share this

prejudice. There is no better way of destroying fear of machines

than to have the novice play a few games with the computer. We

have noted this phenomenon several times, particularly with our

visiting alumni. And most of the games have been programmed by

our students, which is an excellent way to learn

programming. [Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a)]

Indeed, from its outset and original design, the BASIC lab at Dartmouth and

the BASIC programming language fostered programming games as a way to learn

about computing. Kemeny and Kurtz encouraged students to add to their

libraries of BASIC programs, and in the 1970s, publications of BASIC games

in the book BASIC Computer Games by David Ahl

and in popular computer magazines further supported learning programming

through games.

This article takes a closer look at FTBALL as a crucial program in the

history of “computer programming for all” while gesturing to the

tension between a conception of

all and FTBALL’s context in an

elite, all-male college in the mid-1960s. FTBALL can be seen as an early

indicator of masculine computing culture (see [

Rankin 2018],

[

Ensmenger 2012]) and a product of American college

football culture, areas where women have played a peripheral but

ever-present role. But FTBALL is

also an early example of

computing for undergraduates, for people outside the hard sciences, and for

fun. That a renowned professor wrote it to be played for free by

undergraduates at a time when computers were generally reserved for

“serious” work in calculation makes it an excellent object of

study for the history of BASIC, early computing education, and accessible

programming more generally. Accordingly, I put FTBALL in a historical,

cultural, gendered context of “programming for all” as well as the

historical context of programming language development, timesharing

technology, and the hardware and financial arrangements necessary to

support this kind of playful, interactive program in 1965.

Using methods from critical code studies [

Marino 2020], I point

to specific innovations of BASIC at the time and outline the program flow

of FTBALL. FTBALL demonstrates a number of features typical of early BASIC,

including

LET as an assignment statement

and the infamous

GOTO and

GOSUB statements for program flow. The

GOTO and

GOSUB statements make FTBALL's program flow difficult to

follow — which is also typical for more complex, early BASIC programs. The

convolution of program flow in FTBALL is both ironic and predictable, given

FTBALL’s popularity and attempt at accessibility alongside the common

critiques of early BASIC program structures. Adding to the code analysis in

this article, I use methods from history of computing, drawing historical

context from archival records held by Dartmouth College Libraries, BASIC

fan sites, a 2014 Dartmouth documentary titled

Birth

of Basic, Joy Lisi Rankin’s

A People’s

History of Computing, the collaboratively authored book

10 PRINT, contemporary BASIC programming

manuals, and a personal interview I conducted with Thomas Kurtz in

2017.

[1]

My combined code analysis and archival approach for FTBALL follows in the

footsteps of Dennis Jerz’s examination of Will Crowther's Colossal Cave Adventure (an early text adventure

game from the 1970s) and Nick Montfort’s work on “Zork” (a game inspired by Adventure) in Twisty Little

Passages. While FTBALL is often credited for its early

influence on sports games and its later variations are noted as popular

BASIC games, it has received little scholarly attention and, to my

knowledge, no attention to the composition of its code nor its early role

in popularizing BASIC. As with Adventure and

Zork, the availability of FTBALL’s code

and its textual interface makes it rich for textual analysis. The

popularity of all three games as early genre entries justifies the extended

attention to their cultural and historical contexts as well. Below, I begin

with a short history of BASIC’s early development, put FTBALL in context

with other early games and sports games, then move into the hardware and

technical details that enabled the code before finally reading FTBALL’s

code in detail. My hope is to provide something of interest to computing

historians, critical code studies practitioners, and games scholars and

aficionados.

BASIC and Accessible Computing at Dartmouth

With the skills and needs of liberal arts students at Dartmouth in mind, math

professors John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz began in the 1950s to work towards

an ambitious goal of teaching the entire undergraduate population of

Dartmouth basic computer literacy. They had begun this project by working

closely with students to develop simplified assembly code. During the early

1960s, they moved through several languages and hardware setups prior to

requesting funds from the NSF and the college for a hardware system that

would support their pedagogical goals. With this support and the ingenuity

of undergraduate collaborators, in 1964, Kemeny and Kurtz launched the

BASIC language and the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS). BASIC went

through several rapid revisions in the mid-1960s, and then spread widely

due to its accessible syntax, generous licensing, and local timesharing

access. BASIC was particularly popular among hobbyists. By 1978, BASIC was

“the most widely known

computer language,” according to Kurtz, because it appealed to

a general audience, or, as Kurtz put it: “[s]imply because there are more people in the

world than there are programmers” [

Kurtz 1981, 535].

Kemeny and Kurtz had lifelong investments in education, and Kemeny had been

involved in nationwide mathematics education efforts prior to BASIC. Kemeny

was a Jewish immigrant from Hungary; he had come to the US at fourteen

years old in 1940 when his father recognized the danger of increasing

anti-Jewish regulations in Europe. His brilliance, especially in math,

shone almost as soon as he arrived: he graduated valedictorian of his high

school in New York and was drafted into the Manhattan Project while he was

an undergraduate in math and philosophy at Princeton. Los Alamos was

Kemeny’s first exposure to computing. Kurtz says of Kemeny: “he had been drafted and sent to

Los Alamos where he worked on the precursor to the atomic bomb.

They had IBM accounting machinery, …adding and subtracting was

the only thing they did. They figured out a way to solve partial

differential equations using equipment, and he was involved in

that” [

Kurtz 2017a]. He came to

Princeton and got a Ph.D. in Mathematical Logic, then joined their

Philosophy Department, after which he was recruited to Dartmouth to lead

the Math Department. Kemeny was connected to some of the most brilliant and

influential thinkers in physics, math, and computing: at Los Alamos,

Richard Feynman was his supervisor and he worked with John von Neumann; at

Princeton his dissertation was supervised by Alonzo Church and he was

Albert Einstein’s mathematical assistant. (Kemeny once remarked that

Einstein needed an assistant because “Einstein wasn’t very good at

math” [

Campion 2001].) Kemeny began at

Dartmouth as a full Professor of Mathematics at twenty-seven, became chair

shortly afterward, then later recruited Thomas Kurtz from Princeton, along

with other colleagues, to build up the Dartmouth Math Department. Kurtz

described Dartmouth at the time: before the interstate highway system,

Dartmouth was “way up here” and isolated, with

only one graduate program — in business administration [

Kurtz 2017b]. But Kemeny was loyal to Dartmouth: he served

over a decade as its president (1970-1981), his two children attended

Dartmouth, and he loved Dartmouth sports.

Dartmouth undergraduates in science in the early 1960s were motivated to

learn how to use computers because the applications for computers were

apparent to them and relatively easy to access with the use of

locally-designed programming languages based on ALGOL. But these languages

had technical limitations and more widely used languages such as ALGOL and

FORTRAN were built for physics and the hard sciences. Kemeny and Kurtz

wanted to reach the other 75% of Dartmouth undergraduates, those who were

majoring in the humanities or social sciences. They figured that these

students would be turned off from computing by the slow turnaround time of

batch processing and specialized languages that relied on arcane knowledge

of computer engineering. For a system to appeal to these students, it had

to be accessible and intuitive and must have quick turnaround times. Kemeny

and Kurtz also knew that lectures on computing wouldn’t cut it; students

actually had to try their hand at programming. So, they worked toward a

system that would simulate real-time responsiveness and have something

closer to English language syntax: what eventually became the Dartmouth

Time-Sharing System (DTSS) and the BASIC computer language [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (b)].

Kemeny and Kurtz wrote:

The

primary goal motivating our development of DTSS was the

conviction that knowledge about computers and computing must

become an essential part of liberal education. Science and

engineering students obviously need to know about computing in

order to carry on their work. But we felt exposure to computing

and its practice, its powers and limitations must also be

extended to nonscience students, many of whom will later be in

decision-making roles in business, industry and

government. [Kemeny and Kurtz 1968, 223]

In their motivations to teach nonscience students to learn more about

computers, the resonances with literacy education are apparent. Thomas

Kurtz confirmed in a personal interview I conducted with him in 2017 that

they did indeed think of their pedagogical project as literacy education.

While they generally described their pedagogical motivations along the

lines of civic engagement, as above, Kurtz also told me they were invested

in the creative potential of the computer. There were others who argued

earlier for computer literacy — George Forsythe in 1959 and Alan Perlis in

1961 — but Kemeny and Kurtz were the first to develop a working system to

support it [

Kurtz 2017b]. Given the hardware and programming

languages of the time, it wasn’t clear to anyone how widespread computer

education could actually work. The LOGO programming language — which

emphasized graphics and was designed for younger children — was developed

very soon after BASIC. Kemeny and Kurtz admired Seymour Papert and the LOGO

development team for their focus on abstract thinking and creativity,

though Kurtz pointed out that LOGO stumbled a bit because it seemed to need

an expert overseeing the learning process [

Kurtz 2017b]. In

contrast, BASIC was designed to be learned with very little support — just

a couple of lectures or a manual. While both BASIC and LOGO circulated

widely with microcomputers in the 1980s, LOGO tended to thrive in formal

educational contexts and BASIC in informal, home, and hobbyist contexts,

including the circulation of games like FTBALL.

Initially, Kemeny and Kurtz were not in agreement about the need for a whole

new language to teach computing but did agree that timesharing was

necessary to keep the interest and attention of nonscience students.

Through a regional computer-sharing agreement with MIT, Kurtz had served as

the Dartmouth representative since 1956 and made trips to Boston every two

weeks to use their IBM 704. He learned Assembly language for the 704 and

would turn in his punch cards when he arrived at MIT in the morning then

pick them up in time to catch the last train back to Dartmouth in the

evening. Kurtz experienced first-hand the frustration of long turnaround

times, as correcting a mistake in his programming meant he would need to

wait two weeks until his next trip to MIT. John McCarthy, an early leader

in artificial intelligence who knew the context at Dartmouth because he had

previously been mathematics faculty there, suggested timesharing during one

of Kurtz’s visits to MIT [

Kurtz 1981]

[

Kurtz 2017b]. Kemeny and Kurtz figured that undergraduates

would tolerate timesharing a computer better than batch processing punch

cards — especially if they were using teletypes that were responsive enough

to disguise the fact that the timesharing was happening.

Through Kurtz’s regular train trips to MIT, Kemeny and Kurtz also learned

that a simpler language was often better than a more efficient one. The

two-week turnaround raised the stakes on errors in their code, even minor

ones. Kemeny and Kurtz used SAP (Share Assembly Language) on the IBM 704

but were frustrated by the complexity and opacity of it. Kemeny devised

DARSIMCO (DARtmouth SIMplified COde) in 1956, although it wasn’t used much

because FORTRAN came out the next year. But, according to Kurtz,

“DARSIMCO reflected

Dartmouth’s continuing concern for simplifying the computing

process and bringing computing to a wider audience” [

Kurtz 1981, 516]. Moreover, after the

difficulties of programming in SAP versus the much more intuitive FORTRAN,

Kurtz recognized “that programming

in higher level languages could save computer time as well as person

time” because the programs were less subject to human error,

even though they might be technically more inefficient. Kurtz initially

thought a subset of ALGOL or FORTRAN would be sufficient for their

pedagogical goals, but the ways those languages treated loops and variables

finally convinced him that Kemeny was right: to teach a general population

of undergraduates, they needed a new language [

Kurtz 1981, 519].

In addition to the need for faster turnaround times and a simplified

language, Kemeny and Kurtz made another early realization: undergraduates

could do serious work in computing. As an undergraduate in 1959, Robert

Hargraves developed the DART language on the newly-arrived LGP-30 computer

[

Kurtz 1981, 516]. Undergraduate George Cooke wrote

a program in DART to predict results in the 1960 election and it predicted

the results correctly — unlike NBC. Stephen Garland wrote an ALGOL

interpreter for the LGP-30 while he was an undergraduate at Dartmouth as

well [

Murray and Rockmore 2014]. When Kemeny and Kurtz applied for

NSF funding to support their pedagogical project, the fact that they had

only undergraduates as assistants apparently made the grant reviewers raise

an eyebrow; however, Kemeny’s reputation carried the day, and they received

their funding anyway [

Murray and Rockmore 2014]. Later, Kemeny and

Kurtz both credited undergraduates as key to the development of the success

of BASIC and DTSS. They noted that in April 1964, their undergraduates

worked 50 hours a week on the system — although they were keen to point out

that none of them failed any courses as a result [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1968, 224–5]. A lot of the actual

development of the language and timesharing system was handled by

undergraduates Michael Busch and John McGeachie; Robert Hargraves and

Stephen Garland also worked on the system. Anthony Knapp had sketched out

an initial hardware configuration draft for timesharing after a visit he

and Kurtz made to GE in 1962 [

Kurtz 1981]. In our interview,

Kurtz repeatedly emphasized the brilliance of the undergraduates working on

BASIC. Referring to himself and Kemeny, he insisted, “we were the leaders of the band; we weren’t the performers”

[

Kurtz 2017b]. That undergraduates were the main audience for

programs also influenced the kinds of programs that got written, including

games.

Dartmouth was aided by the talent and energy of undergraduates as well as the

fact that the university had very little government-supported research and

thus was freed from the apparent constraint to charge faculty and students

for computing services. Kemeny and Kurtz were dead-set on open access of

computing resources at Dartmouth, using open stack libraries as a model.

Kurtz recalled, “At the time, Dartmouth had of one

of the largest, if not

the largest, open stack

library among universities in the country. So, the idea of open

stack, open computing, open access computing is natural and

obvious” [

Kurtz 2017b]. Universities

had different tactics for supporting recreational use of computers at the

time — Kurtz insisted they weren’t necessarily iconoclastic in this.

Princeton apparently had a small block of time for “unsupported”

computer use. Dartmouth, which was more focused on undergraduate education,

had a more open policy, which charged all uses of the computer to the Dean

of the Faculty, who had the budget for the computer, and the Dean then

charged government grants for the use. Kurtz called this a “fictitious charging scheme,” which enabled the

computer to be available at Dartmouth like an open stack library [

Kurtz 2017b]. John McGeachie, who worked on BASIC and DTSS

as an undergraduate, confirmed the availability of the system: “the undergraduates who

were part of the student assistantship program basically had

priority of access to the machine. For all intents and purposes,

it was our machine — which we shared with John Kemeny” [

Murray and Rockmore 2014].

Dartmouth College was the site of other important early innovations in

computing, including a demonstration in 1940 by George Stiblitz of Bell

Telephone Laboratories — the first use of a computer over a communications

line and using a teletype. The “Dartmouth Summer

Research Project” organized by then-faculty John McCarthy in

1956 was first to use the term

artificial intelligence as well

as the birthplace of LISP. Thomas Kurtz pointed to these historical events

as priming Dartmouth for BASIC [

Kurtz 1981].

The fact that Dartmouth attracted such attention to computing was key to the

development of DTSS and BASIC, but even more important was that Dartmouth

is a small liberal arts university, focused on undergraduates as both

researchers and students. Kemeny and Kurtz were savvy enough to align their

goals with the goals of the institution: “the

administration and the Board of Trustees of Dartmouth gave us

their full support as they, too, realized and accepted the goal

of ‘universal’ computer training for liberal arts

students” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1968, 223].

Myron Tribus, then the Dean of the Thayer School of Engineering and a

staunch advocate of Kemeny and Kurtz’s work, wrote of the original design

principles behind Dartmouth computing:

I remember

quite vividly an afternoon conversation with John Kemeny in which

we agreed that certain requirements would be met even if it meant

indefinitely postponing the computer. - Students would have free access.

- There would be complete privacy. No one would know

what the students were doing.

- The system should be easy to learn. The computer

should contain its own instructions.

- The system would be designed to save the time of the

user even if it appeared that the computer was being

“wasted.”

- Turnaround time should be sufficiently rapid that

students could use the system for homework.

- The system should be pleasant and friendly.

Kemeny

and Kurtz stayed true to this vision in the technical and semantic

decisions they made for BASIC, how the student computer time would be

charged, and in the social structure they set up in the computing lab.

With computer literacy as a goal — rather than any grant-sponsored research

agenda — the Dartmouth computing project could embrace uses of the computer

that would engage students. FTBALL was an example of one of those engaging

uses of the computer. As Kemeny and Kurtz noted in their final grant report

for the NSF, the use of computers for games is not frivolous at all. They

maintained that there was no better way to dispel fear of the computer than

to play games, and that programming games was a great way to learn

computing.

BASIC FTBALL as a computer game

The high expense of early computing and the seriousness of it — applications

for war and big science such as ballistics, cryptography, engineering and

physics — would seemingly work against its recreational applications. But

there was a playful side to computing from the start. The Mark II at

Manchester had a loudspeaker that emitted sounds from certain instructions,

and Alan Turing discovered that “the hooter” could produce musical

notes by repeating these instructions. In an all-night programming session,

Christopher Strachey composed “God Save the

Queen” with these instructions and, consequently, landed

himself a job at the lab. A recently restored recording session from 1951

captures this plus “Baa Baa Black Sheep” and

“In the Mood,” composed perhaps

collaboratively by Strachey and other members of the lab [

Copeland and Long 2016]. In 1952, Strachey wrote a “Love Letters” program that spat out saccharine

and silly statements such as “DARLING CHICKPEA, YOU ARE MY AVID

ENCHANTMENT” signed “M.U.C.” for Manchester University

Computer [

Wardrip-Fruin 2009]. Allen Newell, J.C. Shaw and

Herb Simon wrote a chess game at Rand Corporation in the 1950s; chess has

been a testing game for AI ever since [

Ensmenger 2012]. The

game

Spacewar! had been written at MIT in 1962

on an inexpensive DEC PDP-1, which had a primitive CRT graphic display.

Spacewar! circulated among university and

business computing site for years and was famously described by Stewart

Brand in a 1972 issue of

Rolling Stone

[

Brand 1972]. IBM attempted to ban it for its unseriousness,

but then rescinded the ban because the game itself was a lab for

computational experiments. “Ready

or not, computers are coming to the people,” Brand wrote [

Brand 1972]. As Brand and so many others recognized in the

1950s and ‘60s, games of all kinds were an ideal conduit for learning about

computing.

So, there was precedent for Dartmouth FTBALL as a recreational use of

computers. And while Kemeny and Kurtz were serious mathematicians, they

recognized that to encourage computing, recreational applications such as

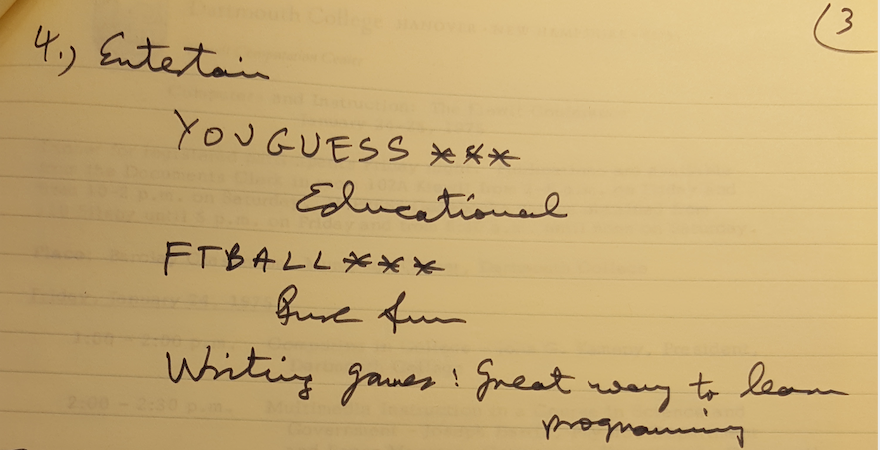

games were key. In his notes for a public lecture, Kemeny noted that FTBALL

was “pure fun” and that “Writing Games” was a “Great way to learn

programming” [

Fig. 1].

FTBALL wasn’t the only game at Dartmouth, either. In the 1967 final report on

their grant for the NSF, Kemeny and Kurtz wrote, “Our library contains some 500 programs, including many games. We

have found that a computer is an efficient and inexpensive source

of entertainment” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a), 6–7]. They go on to describe the games briefly: “The student can challenge the computer to a game of

three-dimensional tic-tac-toe, or quarterback Dartmouth's

football team in a highly realistic match against arch-enemy

Princeton. The program is somewhat biased — Dartmouth usually

wins” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a), 8]. A

local survey in 1967 revealed that Dartmouth students used the computer for

leisure one-third of the time and enjoyed playing games [

Thomas Kurtz Papers, Box 6]. The other

games in the local library of programs were compelling, but FTBALL was

exceptionally popular.

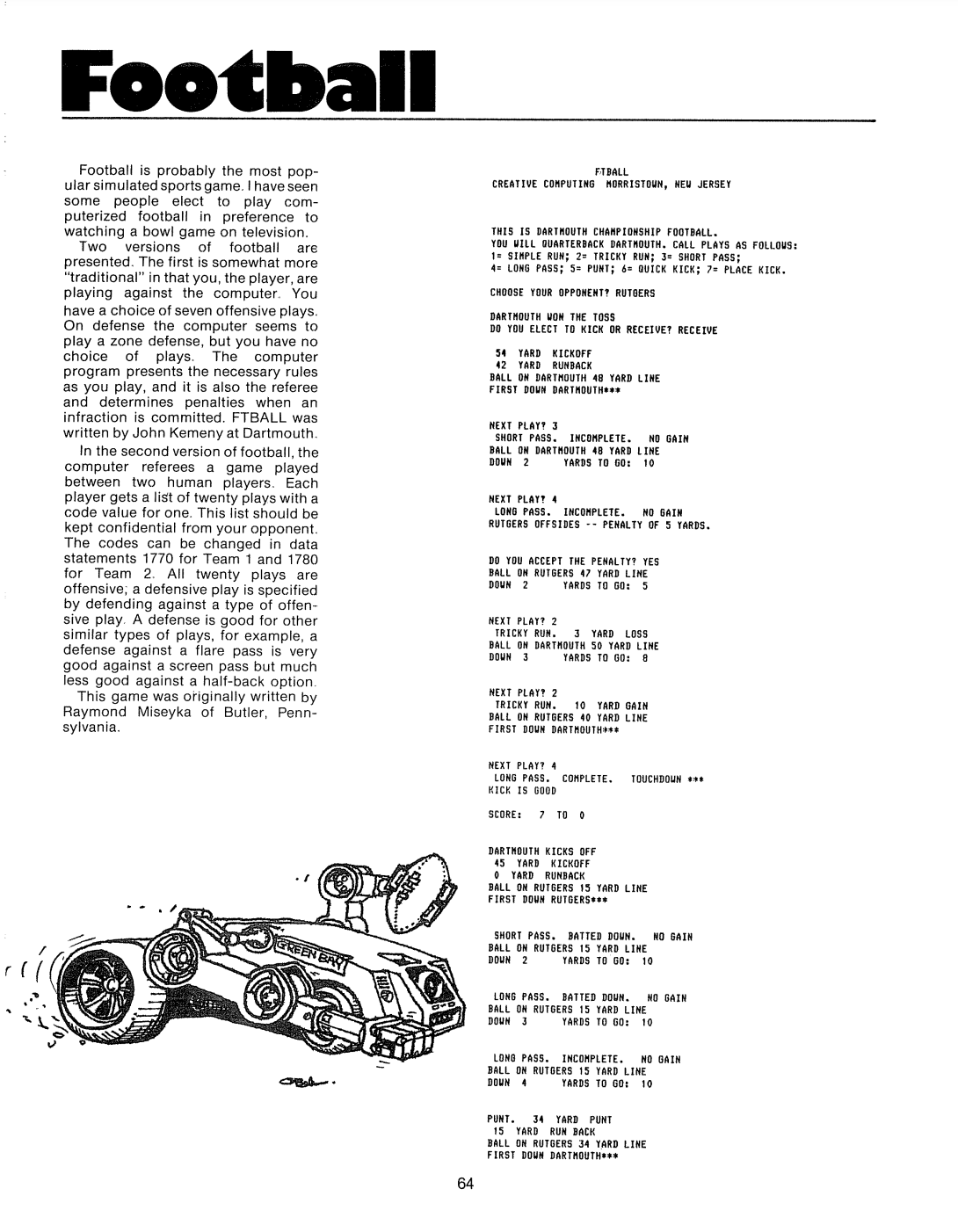

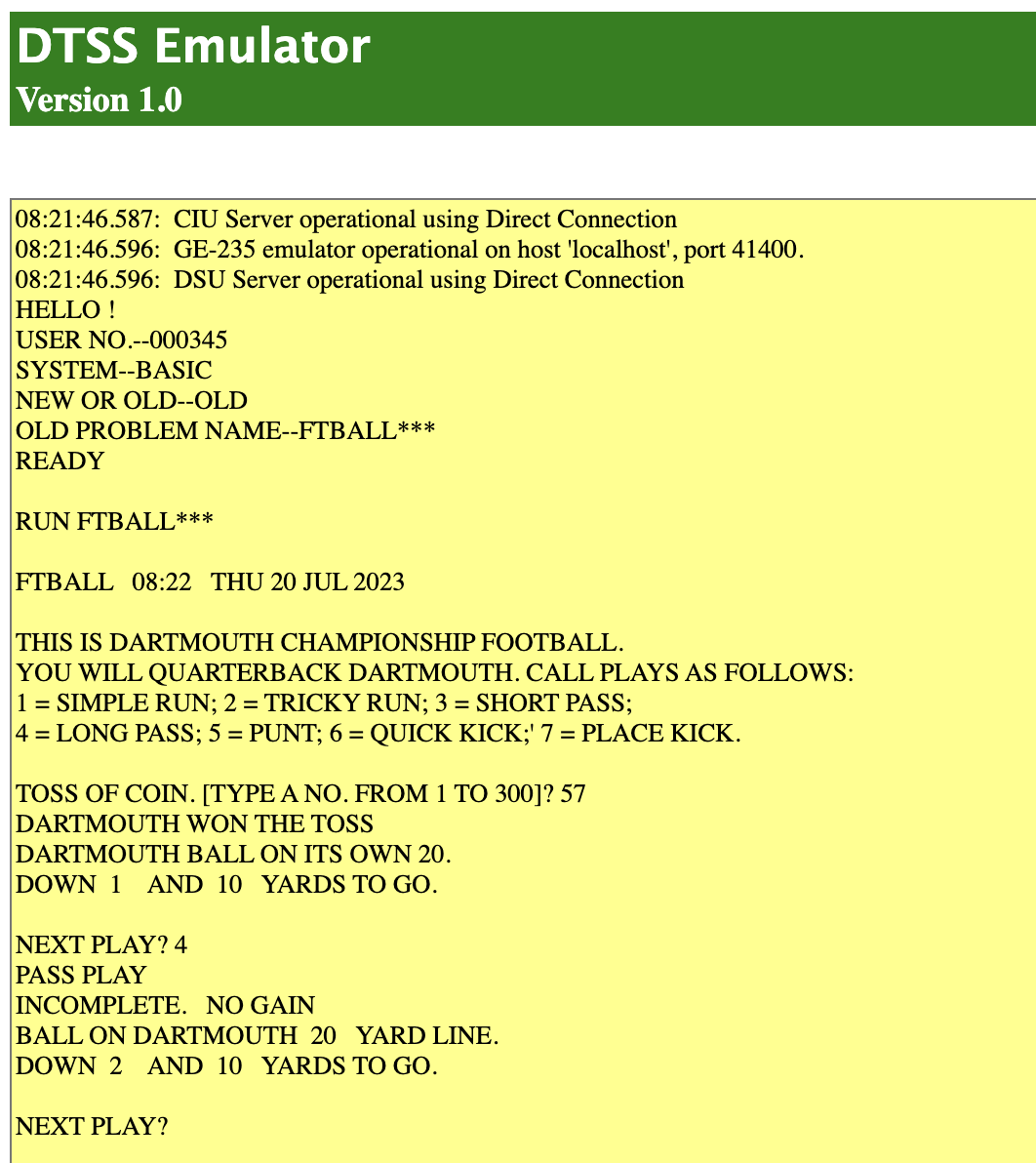

In Kemeny’s first version, FTBALL was a one-player game, though later

versions were multiplayer. A more detailed explanation of how the code

worked is in a subsequent section, but here is the basic gameplay. The

player — likely a Dartmouth undergraduate associated with the lab, or with

connections to it — would queue up FTBALL from the lab’s library and be

greeted with this opening:

THIS IS DARTMOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP FOOTBALL

YOU WILL QUARTERBACK DARTMOUTH. CALL PLAYS AS FOLLOWS:

1 = SIMPLE RUN; 2 = TRICKY RUN; 3 = SHORT PASS;

4 = LONG PASS; 5 = PUNT; 6 = QUICK KICK;' 7 = PLACE KICK.

TOSS OF COIN. (TYPE A NO. FROM 1 TO 300)

The game features typical football plays familiar to any fan, so no further

explanation was given. Note that although the game is played against

Princeton, Princeton isn’t mentioned initially, and the player can only

quarterback for Dartmouth. After this intro prompt, the player then enters

a number for the coin toss, which results in either Princeton or Dartmouth

winning the coin toss and the console’s printout indicating

PRINCETON WON THE TOSS or

DARTMOUTH WON THE TOSS. For either team’s

kickoff, the ball starts on the team’s own 20-yard line, which simulates

the team taking a knee at the kickoff. When Dartmouth is on offense, the

player can then input plays 1-7; however, when Princeton is on offense, the

program chooses plays for Princeton. The program kept track of who was on

offense, yardage for plays, downs, position on the field, and gave results

of plays such as interceptions, successful kicks, and touchdowns. The game

continued for at least 50 plays, and each play beyond that had a 20% chance

of ending the game. The game ending indicated a final score:

END OF GAME ***

FINAL SCORE: DARTMOUTH S(2); PRINCETON S(0)

The console printed the value of the variables

for Dartmouth’s and Princeton’s score, and the FTBALL program ended.

A public conversation between Nancy Broadhead, an operator and self-described

“housemother” at the lab, and John Kemeny at the National

Computer Conference in 1974 provides some context for FTBALL’s origin and

role at Dartmouth computing:

| Nancy Broadhead | Speaking of phone calls and things, one of probably the

earliest programs in the program library was FTBALL. A lot

of us here know who wrote it. I remember one night we had

been apparently having some problem somewhere along the line

and I got a phone call at home one night to tell me in

absolute panic, “FTBALL has been clobbered in the

library!” I live a good half hour away from

Dartmouth and I really wasn't about to jump in the car and

trot in to reload it from cards, or paper tape was probably

what we had for backup at that point. So I just sort of

sleepily said “Well, I'll put it back in the

morning.” [To Kemeny:] What did you really expect

me to do? |

| John Kemeny | We were probably trying to recruit a new football coach and

that seemed so terribly important. I don't remember who

wrote it [Kemeny was being facetious here!] but I do

remember when that program was written, it was written on a

Sunday. Those were the good days when time-sharing still ran

on Sundays. It was written on Sunday after a certain

Dartmouth-Princeton game in 1965 when Dartmouth won the

Lambert trophy. It's sort of a commemorative program. |

Kemeny’s playful refusal to claim authorship of the program in front of an

audience who would have known otherwise recalls the playfulness of the

program itself.

[2] And yet

his description of the possible context that drove him to call Broadhead

after-hours also suggests that the program was more than fun: it served as

a demonstration program for a non-expert to see what Dartmouth computing

could do. In their report on the grant, Kemeny and Kurtz write, “We have lost many a distinguished visitor for

several hours while he quarterbacked the Dartmouth football team

in a highly realistic simulated game” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a), 6–7]. Kemeny’s FTBALL

game, written on a Sunday in response to a real-world game between

Dartmouth and Princeton, would have appealed to the local undergraduates,

but it also had real-world applications for recruiting and impressing

distinguished visitors.

Games, including FTBALL, were among the more popular exports of the Dartmouth

computing library over the DTSS network that included local high schools in

Hanover and neighboring Lebanon as well as regional colleges.

[3] Members of the network also wrote games, exemplifying

Kemeny and Kurtz’s claim in their final grant report to the NSF in 1967

that “most of the games have been programmed by our

students, which is an excellent way to learn programming”

[

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a)]. Rankin names a few of the projects of

students listed in the

Kiewit Comments from

1967, including solitaire by 12-year-old David Hornig and checkers by

13-year-old Julia Hawthorne [

Rankin 2018, 77]. Game

programs were popular at Exeter Academy, an exclusive, all-male (at the

time) prep school 100 miles southeast from Dartmouth College that joined

the Dartmouth network early on. John Warren, the collaborating teacher at

Exeter who later trained other secondary school teaching partners when they

joined the network, claimed in 1966 that Exeter “students and faculty have written several thousand programs,”

and that games were not “idle pasttimes” because

writing them took serious skill [

Rankin 2018, 81].

Traditional sports and card games such as football were early entries in

American computer gaming in part because of their cultural familiarity —

they required few directions to players. Moreover, the scoring of

traditional card and sports games could be represented in numbers, which

computers handled easily. Many Americans already knew the basic rules for

solitaire, checkers, tennis, and football, so they could draw on existing

knowledge to play these games in the limited interfaces of early computers.

It’s perhaps no accident that

Tennis for Two

was the first known interactive video game (written with graphics on an

oscilloscope), followed by the popular

Pong by

Nolan Bushnell in 1972 [

Anderson 1983]. A space game Bushnell

released in 1971 sold few units, but the stripped-down interface of

Pong and the relatable action of hitting a ball

across a net led to

Pong’s huge popularity a

year later [

Wills 2019, 7]. Like FTBALL,

Pong and

Tennis for

Two were iterations of a game many people already knew how to

play. Preceding arcades and graphical interfaces of later football games,

FTBALL was a purely textual and turn-based game, but in 1965, sports fans

would have been familiar with radio broadcasts of play-by-play commentary

in football and baseball.

[4] Consequently, the low-bandwidth of the game’s textual

version of football would not have seemed so clunky to contemporary users

as it might to modern players used to graphical depictions of games.

Later football games, arguably influenced by FTBALL, have been big players in

the genre of sports games.

Atari Football

(1978) was popular in arcades, as was Atari’s home version for VCS, which

was released the same year. Home console football games for the

Intellivision and Nintendo NES continued the trend with

NFL Football (1979),

10

Yard Fight (1983) and

Tecmo Bowl

(1987) [

Wills 2019, 34]. Then came one of the most

popular video game franchises ever:

John Madden

Football, released in 1988 by Electronic Arts and again yearly

since 1990.

Madden combines complex plays and

detailed graphics with official licensing from the American National

Football League (NFL), enabling former NFL coach and famous football color

commentator John Madden to narrate plays that reflect real NFL strategies

and recognizable NFL players and franchises.

Madden is often seen as the first game that non-computer

nerds took up beginning in the early 1990s. It also drew new fans into

football by teaching scoring, plays, and strategies. More recent versions

even include mechanics about team rosters and salary caps, so players learn

about the NFL as well as the plays and strategies of football. Because so

many current NFL players and coaches now grew up playing it,

Madden has influenced the sport itself [

Foran 2008], an interesting reversal from early computer

games influenced by sports.

Because they translate well and rely on cultural knowledge not associated

with computing knowledge, sports games have helped to bring computer games

to a wider audience. Sports games also affected the evolution of computer

games more generally, according to John Wills in

Gamer

Nation:

[T]hese early sports games

enshrined the medium of video games as fundamentally sport-like

and competitive. The opportunity to play American sports proved

eminently attractive, and game consoles sold on their strength of

sports titles. Video games served as an extension of fan service,

part of the ritual of following favorite teams and championship

events… [Wills 2019, 35]

FTBALL is

thus part of this early lineage of fan service, both at Dartmouth

specifically — it celebrated a Dartmouth championship game, after all — and

in sports and computer games more generally.

Examining the cultural context, Rankin associates the popularity of FTBALL

and its subsequent iterations with the masculine culture of Dartmouth

computing. Dartmouth then and now is associated with a kind of “jock”

culture and was all-male at the time Kemeny composed FTBALL. Rankin drew on

interviews and archives to describe the Dartmouth computing lab scene in

which FTBALL was played: Dartmouth men courting women students from nearby

Mount Holyoke College, prank-calling teletypes, error messages that ribbed

fellow student-workers, and frequent late night computing sessions. The

participants and culture of the lab were inevitably shaped by the

demographics of Dartmouth at the time. And beyond Dartmouth, dominant

masculinity in computing spaces shaped the culture and kinds of programs

developed in these spaces. Games of contestation — especially those that

echo the masculinity of fighting, war, and sports — figure prominently in

computing game history [

Wills 2019]. This dominant and

dominating thread of masculinity in computing and in gaming is being pried

apart by contemporary historians of computing such as Rankin, Janet Abbate,

Mar Hicks and Nathan Ensmenger. The scene at Dartmouth computing in the

basement of College Hall was certainly shaped by the fact that all the

students were men, most of them white and some from affluent backgrounds,

although many of the students who worked with Kemeny and Kurtz did so

through work-study support [

Murray and Rockmore 2014]. It is

important to note however, that Kemeny and Kurtz, as math Professors, did

not have control over the student body’s composition at the time. Later, as

President of the College, Kemeny pushed for and presided over Dartmouth’s

1972 transition to co-education, along with developing programs to expand

Native American student enrollment [

Campion 2001].

Kemeny was an avid fan of Dartmouth football, and he often attended games

with his math colleagues. As one of his colleagues recalled, “They made all manner of bets based on probabilities

of obscure game occurrences, such as the odds on three flags

being thrown twice in a quarter” [

Campion 2001]. Kemeny wrote FTBALL on Sunday, Nov 21, 1965, a celebration

of Dartmouth winning the Lambert trophy in a surprise upset against

Princeton on Nov 20, 1965.

[5] The game featured in FTBALL is between Dartmouth and Princeton, but

Princeton isn’t in the title — it’s

Dartmouth Championship

Football. The title and the opponent, a major Ivy League rival, presumes an

internal audience of Dartmouth football fans. As Kemeny and Kurtz admitted,

“The program is somewhat biased —

Dartmouth usually wins” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (a), 8]. Quarterbacking for Dartmouth, users could choose

among seven different running, passing, and kicking plays. At the time that

Kemeny wrote the game, BASIC was interactive — it could take input from the

user unlike earlier versions of BASIC — but it wasn’t yet capable of

multiplayer games. A later iteration of FTBALL was multiplayer and

announced as

FOOTBALL in the Nov 1969

Kiewit Comments newsletter [

Rankin 2018, 48]. Rankin noted the significance of this

networked version, as it meant that students at Kiewit could play

FOOTBALL with others in the local DTSS New

England network, including secondary schools and other colleges in the area

[

Rankin 2018, 48–49].

Beyond the Dartmouth network, the offspring of Dartmouth Championship FTBALL

had longstanding appeal outside of Dartmouth as well.

FOOTBL (“Professional football”)

and

FOTBAL (“High School

football”) circulated in the first BASIC computer games book,

written by David Ahl and published by DEC in 1973 [

Good 2017]. The 1978 edition featured Dartmouth Championship Football with the

byline of Raymond Miseyka, though credit was given in the accompanying text

to John Kemeny for the original version. The 1978 version of FTBALL is

clearly based on Kemeny’s: for instance, it features Kemeny’s original

seven plays. It augments Kemeny’s original by allowing the user to input an

opponent name, handling errors, and including chance events like “

GAME DELAYED. DOG ON THE

FIELD.” This line refers to a bizarre but regular

occurrence in 1960s Dartmouth football: wild dog stoppages. According to

Jean Kemeny’s memoir

It’s Different at

Dartmouth, wild dogs often ran free on campus and then

occasionally on the football field during game days, where they would delay

play.

[6] In the version from Ahl’s book, the remark (REM) reads: “JEAN’S

SPECIAL,” suggesting this feature was added by Kemeny. The fact

that Miseyka’s version works from Kemeny’s is further indication of the

free circulation of BASIC games during this period. As the authors of

10 PRINT demonstrate, the BASIC language

and programs traveled widely and freely and thus shaped computational

culture in the 1960s through the 1980s [

Montfort et al 2014].

In the “Acknowledgements” of

BASIC Computer Games, Ahl thanks Dartmouth

College “For recognizing games as a legitimate

educational tool and allowing them to be written on the Dartmouth

Timesharing System” [

Ahl 1978, xi].

Ahl also thanks Microcomputer Manufacturers “for putting computer games within the reach of every

American in the comfort of their own home.” The first wave of

mass-market home computers hit just prior to his publication; many of them

shipped with a version of BASIC preinstalled, and games were indeed a

popular application — both the playing and writing of them. Although the

success of BASIC with home computers wasn’t necessarily anticipated by

Kemeny and Kurtz, the technical decisions they made about the language as

well as the way they allowed it to freely circulate were key to its

popularity.

Hardware and technical details

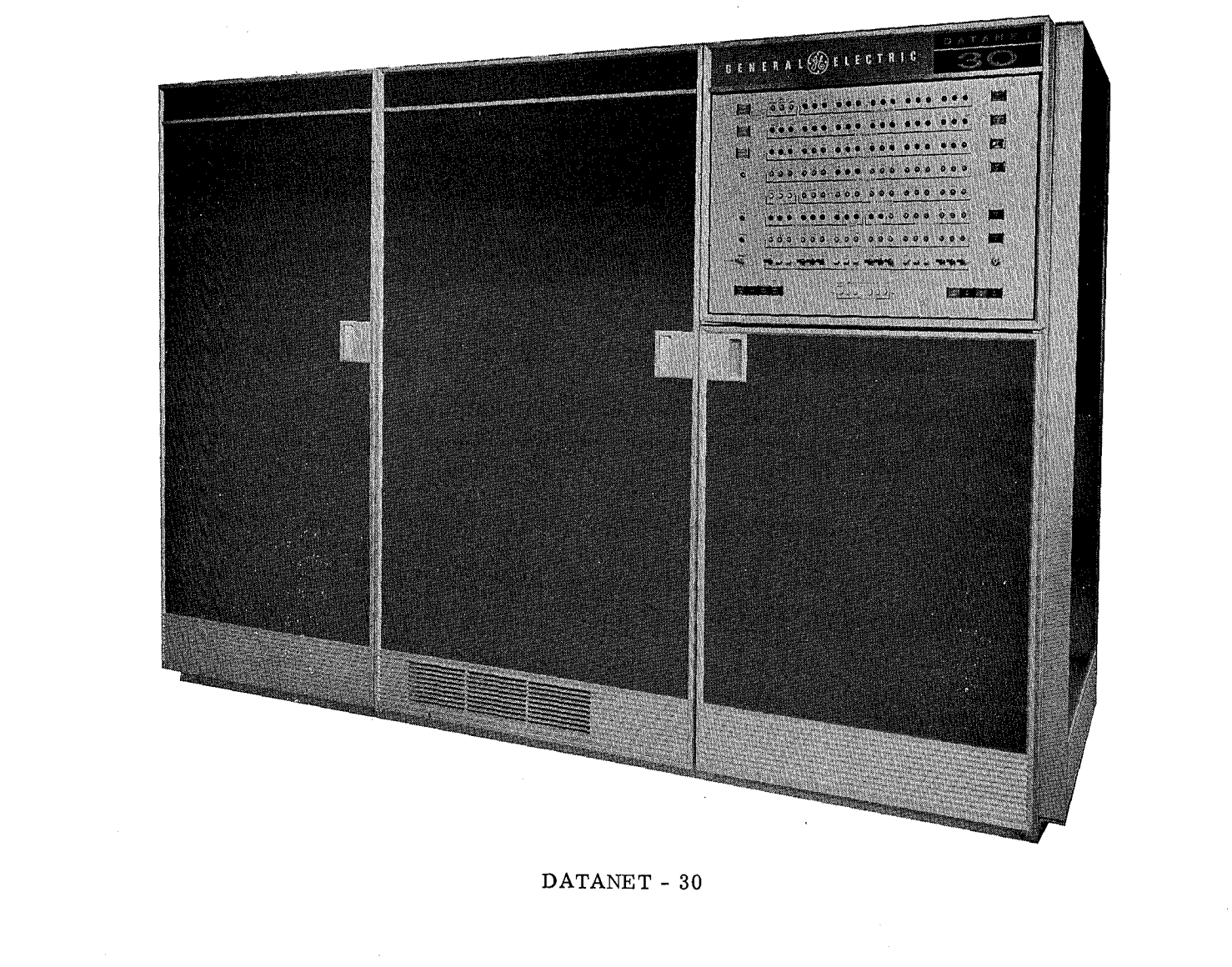

Early versions of BASIC and DTSS ran on GE computer hardware, which was

purchased with the NSF grants that Kemeny and Kurtz obtained, support from

Dartmouth College, and discounts from GE.

[7] The

first iteration of BASIC/DTSS (Phase I), which ran from 1964 to sometime in

1967, ran on two computers: a GE-235 to execute programs and a GE

Datanet-30 to handle communications with the teletypes and to schedule the

execution of programs on the 235 [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (b)].

Undergraduate Anthony Knapp had designed an early version of this setup

with Kurtz [

Kurtz 1981, 532]. Kemeny had borrowed a

GE-225 in the Boston area to prototype the BASIC compiler in 1963, and

Kurtz and undergraduate Mike Busch ‘66 traveled to GE in Phoenix, Arizona,

to learn how to program the equipment [

Dartmouth College]. The

Dartmouth team called the resulting hybrid system the “GE-265” because

it was a marriage between the GE-235 and Datanet 30.

[8] As Kemeny and Kurtz wrote in 1968, this two-part

“system anticipated the current

understanding that communication, not calculation, is the primary

activity in a time-sharing system” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (b), 226].

[9] The DTSS thus signaled

a new computing paradigm: the most exciting challenges and affordances of

computer systems in the 1960s were related to communication as opposed to

the calculation paradigm of the previous decade.

Jerry Weiner was the GE project manager working with the Dartmouth team; he

flew in system parts when they burned them out. He noted that: “Although the Datanet 30 was standard off the shelf,

it was standard off the shelf numbered double zero and one of ten

unique machines. We rebuilt it without telling other

people” [

American Federation of Information Processing Societies 1974, 2]. Kurtz

provided more detail on their choice of the GE system when I spoke with him

in 2017:

We looked around for computers that we

thought could do time-sharing. Now, there was no timesharing

software available in the market, but we were looking for

computers which would lend themselves to this. And we got

proposals from four companies or something like that. Including

IBM proposed something similar to what they were doing down at

MIT, and others. BENDIX proposed something, and General Electric

had a computer department in those days, and for some strange

reason they had their regular computer which was called GE-225,

which is an old-fashioned machine that used punch cards and so

on. Then they had another computer which was designed to support

a teletype communication network, they called it the DATANET-30,

and it was designed to allow teletypes to communicate the same

way as phones. […] [The main machine had] floating point

hardware, which we felt was essential. […] I don’t know what the

application was that they were thinking of, but along the way —

and I don’t know if they really knew what they were doing — along

the way they figured out a computer interface unit to put these

two computers together. They hadn’t done anything with it, but

that was available as something you can buy from

them. [Kurtz 2017a]

The descriptions

from Weiner and Kurtz are indicative of computing hardware at the time:

even the off-the-shelf systems were bespoke and uncharted.

The GE-225 had been designed, in part, by Arnold Spielberg, the father of

Steven Spielberg. In an internal GE publication, the younger Spielberg

recalled,

I remember visiting the [GE plant in

Phoenix, AZ] when dad was working on the GE-225....] I walked

through rooms that were so bright, I recall it hurting my eyes.

Dad explained how his computer was expected to perform, but the

language of computer science in those days was like Greek to me.

It all seemed very exciting, but it was very much out of my

reach, until the 1980s, when I realized what pioneers like my dad

had created were now the things I could not live

without. [GE Reports Staff 2015]

The GE-225 was designed in 1959, and with dozens of early sales, it was a

marketing success. Several banks bought the GE-225, and a machine at First

Union National Bank predicted the 1964 Johnson-Goldwater race. Related to

FTBALL, a GE-225 was used by the Cleveland Browns for ticket sales. As

GE Reports quotes, “‘Who knows,’ quipped the Browns’

president Art Modell in 1966, ‘there might come a

time when computers will help call the next play.’”

[

GE Reports Staff 2015]

BASIC was designed with a teletype interface rather than punch cards for

accessibility reasons [

Kurtz 1981, 521]. Along with

better teletypes for interfacing, the development of ASCII in 1963

“came along in the nick of

time” [

Kurtz 1981, 519]. Following

up on his description of the “GE-265” setup, Kurtz narrated:

Then we would set this up and the whole

idea was, we would put teletype machines in the various

departments around on campus; we’d have a place where students

could go and sit on a teletype machine and write

programs. [Kurtz 2017b]

When FTBALL

was written (1965), there were about 30 of the Teletype Models 33 and 35

terminals around campus and the computing lab was located in College Hall.

They were planning to replace the hardware with a GE-635 and move to a new

building; the Kiewit Center was dedicated in 1966 [

Kurtz 1981, 528]. With this bespoke hardware setup for FTBALL sketched out,

we can move into the language design of BASIC at the time.

BASIC as a beginner’s language

In the early 1960s, computation was at such a premium that most computer

experts believed that languages needed to prioritize computational

efficiency at the expense of usability. Mark Marino discusses John von

Neumann’s supposed response to FORTRAN as a more accessible language: he

believed that it was a waste of computer time to have it do the clerical

work of legibility and style. This tradeoff takes on a gendered meaning

given that clerical staff and computer technicians were often women, while

the machine language writers and designers were men [

Marino 2020, 149]. Kemeny and Kurtz did not share von

Neumann's view. Kurtz had come to the realization — after finding FORTRAN

more efficient than assembly languages, which were more prone to human

error — that the tradeoff between human use and computational efficiency

wasn’t so simple. A language that was easier to use would be quicker for

students to learn, more students could learn it, and they would be more

successful in their programs. Kurtz explained in an internal memo from

1963: “In all cases where there is a choice

between simplicity and efficiency, simplicity is chosen”

(quoted in (

Kurtz 1981),

520).

Consequently, a number of technical decisions were made in BASIC to

prioritize simplicity and legibility of the language over computational

efficiency.

Some examples of technical choices Kemeny and Kurtz made to simplify BASIC

include: hiding

object code from the user, who could make

edits directly in BASIC by using line numbers; keeping case-insensitivity

even when 8-bit ASCII allowed for both upper and lower case; and reducing

compiling time by skipping an intermediary language [

Kurtz 2017a]. BASIC treated numbers in ways that valued an

intuitive sense of users over computation time. For example, BASIC

“wasted” computer time by treating all numbers as

double-precision floating point numbers, the most computationally expensive

and precise representation of numbers at the time, rather than having users

specify number type.

[10] Moreover, the user didn’t need to

know about formatting the number for printing, as other languages

required.

Commands in BASIC were designed to be

friendly (see the

Tribus memo quoted above) and written in

non-technical words lay English speakers would understand. BASIC used

monitor commands such as

SAVE,

HELLO,

RUN,

GOODBYE instead of

LOGON and

LOGOFF. Short error messages in English and limited to only

five messages per run of the code worked toward simplification as well as

good pedagogy [

Kurtz 1981, 522]. The use of English

words and commands in BASIC were thought to make the program easier to

understand. Of course, this assumes users would know at least basic English

vocabulary, which was the case for any Dartmouth College student. In his

analysis of FLOW-MATIC, which also relied on English vocabulary to make

programs ostensibly easier to read,

Marino

breaks down some of the challenges to English-syntax as accessible

programming design (

149-152). Beyond the

obvious critiques of Global English as a tool for colonization, because

languages like FLOW-MATIC, COBOL, or BASIC cannot handle the complexities

of English syntax, they end up reading as stilted and awkward rather than

the

natural language they aspire to. Whether they are more

legible than more abstract symbolic representation is a matter of debate.

However, for the very newest users who might be turned off by jargon — the

very users Kemeny and Kurtz were aiming for — the friendlier “HELLO”

might have helped them overcome an initial fear of computing.

Given BASIC’s purpose as a learning language, Kemeny and Kurtz built good

pedagogical principles of composition feedback into the system itself. To

encourage students to correct their own errors, Kemeny and Kurtz designed

the compiler not to check line by line prior to compiling [

Kurtz 1981, 522]. As they wrote in 1968, “We find the instantaneous

error messages of other systems annoying and a waste of time. It

is very much like having an English teacher look over your

shoulder as you are writing a rough draft of a composition. You

would like a chance to clean up a draft before it is

criticized” [

Kemeny and Kurtz 1968, 227]. This insight aligns with best practices in writing feedback,

especially in Writing Center research, that instructors giving too much

attention to lower-order concerns such as individual grammar errors can

detract from a writer’s own recognition of error patterns.

Though they steered away from instantaneous error messages that would

discourage self-correction, Kemeny and Kurtz realized that rapid response

was key for a timesharing system. Batch-processing, where a computer tech

feeds in cards and users receive results hours later, was not going to work

for casual users. But Kemeny and Kurtz saw that if users received a

response to their program in less than 10 seconds in a timesharing system,

users had the helpful illusion that the computer was

theirs

[

Kemeny and Kurtz 1968, 227]. Interpreted languages could

provide this more rapid feedback; however, they were more computationally

expensive. Had BASIC been an interpreted language, it would have been

prohibitive to run anything more complex than the simplest programs on the

hardware they had available. Consequently, early versions of BASIC,

including the one FTBALL is written in, were compiled rather than

interpreted. Later versions of BASIC for minicomputers such as the PDP/8

were interpreted [

Kurtz 1981, 523].

Recognizing the value of rapid feedback, Kemeny and Kurtz worked toward the

one-pass ideal that interpreted languages offer by implementing a

pass and a half system to speed up compiler time for

BASIC [

Kurtz 1981, 522]. The BASIC compiler could handle

everything in one pass,

with one exception — a

GOTO statement could refer

to a point later in the program, a point not yet reached by the

compiler. The solution was to produce a linked-list of the

location of GOTO statements in

the student’s program. At the end of the compile main run, it ran

through the linked list, filling in the blanks. We sometimes

called it a “pass and a

half.” [Kurtz 2017a]

BASIC scaled well for more complex programs by using this

single-pass plus linked-lists compiling design.

Earlier language development and experimentation set the stage for the

development of BASIC, giving Kemeny and Kurtz key insights on what language

features were critical to a student-oriented system and simplified user

interface. At Dartmouth, they developed ALGOL 30, so-named because it ran

on the LGP-30, which could not run a full implementation of ALGOL 60, an

influential and popular language at the time, especially among academics.

From ALGOL 30, which had to be run on paper tape and was a two-pass,

batched system, they learned that “the delays between presenting the source code tape and the execution

were too great to allow for widespread student use.”

Subsequently, undergraduate (and later faculty member) Stephen Garland

developed SCALP (Self Contained ALgol Processor), to avoid batching. The

success of SCALP (hundreds of students learned it at Dartmouth in the early

1960s) taught Kemeny and Kurtz that quick turnaround and use of only source

language for programming and patching were key for a system that might have

wider implementation among students [

Kurtz 1981, 517].

DOPE (Dartmouth Oversimplified Programming Experiment, written by Kemeny in

1962) was also a precursor to BASIC and contributed, among other things:

line numbers that served as jump locations; interchangeable upper and lower

case letters; printing and input formats [

Kurtz 1981, 518].

Line numbers were how a BASIC program in 1965 managed program flow and edits.

BASIC programs were typically organized by line numbers counted by 10s,

which left space in-between for additions. Every line that began with a

number was assumed by the system to be part of the program, and (through

the

pass and a half system) line numbers were automatically

sorted in order so that additions, deletions and edits could be appended

and then sorted correctly into the program flow at compile time. Commands

that didn’t begin with line numbers were read as monitor commands [

Kurtz 1981, 521].

The

GOTO command was used in program flow to

jump to different parts of the program, often after conditional statements,

e.g.,

GOTO LINE 20.

GOTO was not an innovation of BASIC, as even

FLOW-MATIC had used the command along with

JUMP

TO

[

Marino 2020, 139–144]. Later, structured languages

allowed for function call by name instead of line numbers and BASIC itself

became a structured language in later versions. But in 1965,

GOTO was the way to direct program flow to

different functions based on input.

GOTO

was famously derided in an article by Edsgar Dijkstra in 1968, “GOTO Considered Harmful”, which launched a whole

genre of computer science articles on “considered harmful” practices

in the profession. Dijkstra was opposed to

GOTO because the unique coordinates of the

GOTO affected program flow but they were

“utterly unhelpful” in tracing the progress

of the program — that is, in the user figuring out just what was going on

when. Moreover, the

GOTO statement is

“too much of an invitation to make a

mess of one’s program” [

Dijkstra 1968].

As a result of Dijkstra’s influence, deriding

GOTO seems almost as popular a sport among programmers as

football. However, the strong claim against

GOTO, especially for understanding program flow, isn’t clear.

Frank Rubin wrote to

Communications of the ACM

in 1987 against the religious belief against

GOTO and pointed out examples where

GOTO reduced complexity in programs [

Rubin 1987]. For new users who are unfamiliar with programming structures, following

program flow by line number is simple. As with many choices for BASIC,

Kemeny and Kurtz elected to implement what might be most self-explanatory

for

new users. With the background of these technical

decisions in the language of BASIC itself, let's move on to the specific

commands and code of FTBALL as representative of early BASIC in 1965.

FTBALL’s code

The code for FTBALL is written in the third edition of BASIC, the first

edition to be interactive — effectively, the first edition that was

conducive to games. The first edition of BASIC was outlined in a reference

manual, likely written by Kemeny; the second edition was described in a

primer, likely written by Kurtz. These documentation shifts from technical

manual to primer indicate how the Dartmouth team was developing the

language to handle a larger scale of users. The third edition added the

INPUT statement to BASIC, which allows

programs to take data from the user. This meant BASIC programs could change

results based on user input. So, a user could play a game and expect the

result of the game to be affected by their choices. The third edition

manual is dated 1966 but since FTBALL was written in the fall of 1965 by

Kemeny, it’s likely he was implementing the newer version of BASIC code

ahead of the documentation of it [

Kurtz 1981, 526].

FTBALL was called that because of a six-character limit for strings in BASIC

at the time. All functions were limited to three characters:

LET,

INT,

RND are examples of such functions

described below. Kurtz later called this decision “unfortunate” for legibility [

Kurtz 1981, 524]. FTBALL also demonstrates the original

BASIC convention of variables consisting of one letter and one number.

Kemeny and Kurtz specified variables this way for the sake of time: shorter

variables were quicker during the computer’s symbol table lookup. Plus,

they figured it was faster to compose programs with shorter variable names

and, because they were mathematicians, they were accustomed to

single-letter variable names. It didn’t seem consequential to have

variables named in this obscure way, although like the three-character

function limit, it later became clear that more descriptive variable names

might make the program easier for users to read [

Kurtz 1981, 523]. But, as with any language design decision, the tradeoffs

were often between legibility and how much space a program would take up.

Characters took up space in memory.

As with every BASIC program of its time, each line of FTBALL contains an

instruction number (line #), operation (such as

LET), and operand (e.g., a variable) [

Kurtz 1981, 522]. And also demonstrated here, all BASIC statements begin

with an English word, including the final

END. Although the ASCII standard had recently allowed for

lower-case letters and BASIC accepted them, the commands for FTBALL are in

all-caps likely because of convention — either lower or upper case would

have been interpreted the same [

Kurtz 2017a].

The BASIC commands in use in FTBALL are (in the order they appear in the

program):

- REM: comments or

remarks. They didn’t pull the syntax of

“comments” from FORTRAN or ALGOL, and Kurtz admits

“the reason is not recorded

for choosing the statement REM or REMARK in BASIC” [Kurtz 1981, 525].

- PRINT: This command prints

characters from the teletype. There were no automatic line breaks

or wrap around on the paper output. Consequently, note that in

the beginning prompt, there are two PRINT lines in a row to force breaking the

directions into two lines. There are blank PRINT lines, too, just to print a

space. (This technique is also featured on the cover of Rankin’s

book.) The PRINT statement

allowed for expressions and quoted material and used the comma as

a separator. Later versions of BASIC required a colon or

semicolon to separate the expression and the quoted material [Kurtz 1981, 524].

- INPUT: reads from a teletype

file. This command made BASIC an interactive language and wasn’t

present in the original BASIC [Kurtz 1981, 521]; it came in the third edition of BASIC. It stopped program

flow and waited for input from the user, prompted by

“?” It was usually accompanied by the PRINT statement to specify what

kind of INPUT was called for. The

semicolon that accompanies the PRINT statement at the beginning of FTBALL allows

the teletype to stay on the same line and character position.

(Alternatively, the comma keeps the teletype on the same line,

but moves the character position over one column, or some

multiple of 15 spaces from the left margin [Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (b), 13].

- GOTO: This is a program flow

command, enabling a permanent jump from one part of the program

to another. GOTO is a sign of

what is now called unstructured programming in light

of later programming languages that controlled program flow by

function name. The command is used here to jump to particular

plays in the program.

- GOSUB: This is another program

flow command, but one which causes a temporary jump in program

flow. The program jumps to a subroutine and then returns back to

where it came from upon the RETURN command. The GOSUB routines in FTBALL are at Line 4100, 4200 and

4300, which are part of the KEEP

SCORE subroutine, so it makes sense that they are

called periodically as interruptions in the program.

- LET: This assignment statement

allows for “LET x=x+1”

rather than the more standard (then and now) x=x+1 because the LET made more sense to novices

[Kurtz 1981, 524]. The similar appearance

of the assignment statement and the equals statement was

confusing to novice programmers (both then and now).

- FOR: This term came from ALGOL,

although the three loop-controlling values (initial, final, step)

came from FORTRAN. Kemeny and Kurtz borrowed “the more natural testing for loop

completion before executing the body of the

loop” from ALGOL [Kurtz 1981, 521].

- NEXT: This command is paired

with FOR and used for stepping

through a loop.

- IF/THEN: This is a conditional

statement common in programming languages then and now. There was

no ELSE statement in BASIC at the

time; the ELSE is implied so that

if the flow isn’t stopped by any of the IFs, then the program flows automatically to the

next statement (see FTBALL Lines 190 and

191). Conditional statements are so fundamental to

programming that we see them first in Ada Lovelace’s writing on

the Analytical Engine, the ENIAC allowed for such jumps, and

they’re in FORTRAN as well. But FORTRAN at the time had 3-way

branching (IF-THEN-ELSE) and BASIC’s was simplified to remove the ELSE.

- RND: This function provides a

number between 0 and 1, not inclusive, to facilitate random

chance in a simulation. As Kemeny and Kurtz explain, “An important use of computers is the

imitation of a process from real life. This is known as

a simulation. Since such processes often depend on the

outcome of chance events, a key tool is the simulation

of random events” [Kemeny and Kurtz 1967 (b), 65]. RND

was one of ten original functions provided with BASIC [Kurtz 1981, 524].

It required an argument, even a dummy one, an issue which they

fixed later.

- INT: This function turns a

decimal number argument into an integer. Originally, it truncated

toward zero — it just cut off any number after the decimal. It

was designed to conform to the common “floor” math function

in the third edition of BASIC. INT is one of the original ten functions of

BASIC.

- STOP: This is the final

statement of the main program flow.

- END: Every BASIC program ended

with this statement.

The main game loop of the FTBALL program begins at line 360, which increments

the number of plays in the game (variable

T) and either sends the program flow to the various possible plays

(1-7, stored in variable

Z) or to the end

game sequence (lines 375-378).

[11] The plays, result of

play, and other possibilities come after that, with

GOTO and

GOSUB used to direct program flow to those possibilities based

on user input. The title to the program is in a

REM (Remark) line and user is greeted with a series of print

statements to initiate the game (the last

PRINT statement simply prints a blank line, and being numbered

45 suggests that it was added later for aesthetic reasons):

0 REM * FTBALL *

10 PRINT "THIS IS DARTMOUTH CHAMPIONSHIP FOOTBALL."

20 PRINT "YOU WILL QUARTERBACK DARTMOUTH. CALL PLAYS AS FOLLOWS:"

30 PRINT "1 = SIMPLE RUN; 2 = TRICKY RUN; 3 = SHORT PASS;"

40 PRINT "4 = LONG PASS; 5 = PUNT; 6 = QUICK KICK; 7 = PLACE KICK."

45 PRINT

In this initial version, there was no option to play for another team — users

had to play for Dartmouth. These numbered plays refer to actual football

plays and so a user familiar with football wouldn’t necessarily need a

description in order to play. Even those unfamiliar with the specific plays

could cycle through them just by entering the corresponding number.

Next, the program initializes three variables that will come into play in the

game:

50 LET T = 0

60 LET S(0) = 0

70 LET S(2) = 0

Other variables that are relevant to the play are set elsewhere:

- Y keeps track of yardage on the

plays

- F marks whether or not a play

has failed (e.g., a fumble or interception)

- X is the yardage position on the

field (Princeton goal is X=100;

Dartmouth goal is X=0)

- Z is the play, according to the

key revealed at the game’s beginning (1-7)

- T represents how many plays have

occurred in the game. The game has at least 50 plays, and each

play beyond that has a 20% chance of ending the game.

- D keeps track of which down the

offensive team is on

The program uses the same code for plays no matter if Princeton or Dartmouth

are on offense, but it marks the distinction between the two with the

variable P: if P=

-1 Dartmouth is on offense and if P=1 Princeton is on offense. The user plays Dartmouth and

calls the plays when they are on offense using the seven options offered at

the start of the game. The block of code beginning with 2680 REM PRINCETON OFFENSE begins the logic

of the computer opponent, or game AI. Princeton’s choice of play on offense

is governed by RND functions, which down

Princeton is on, and how many yards to go. Kemeny could have had Princeton

just randomly select a play 1-7, but this (somewhat dizzying block) of code

provides a little strategy for the computer opponent, making the game more

realistic and unpredictable — and probably more fun.

The code allots space for failures on plays such as interceptions and

fumbles, which are marked with the variable

F. Some aspects of the game are not simulated. For instance,

the kickoff return results in the opposing team getting the ball on their

20-yard line, as if they had taken a knee upon receiving an average

kickoff. The variable

T counts the plays in

the game up to 50, at which point the game ends or has an 80% chance of

continuing.

S(0) is Princeton’s score and

S(2) is Dartmouth’s score; these are

arrays that store values based on the results of plays. They are updated in

the

LINE 4000-4220 block and are printed at

LINE 4200 and in the end game

sequence. The

GOSUB routine is one way the

program flow gets to the score code block, and then the

RETURN takes the program back to where it

left off:

4200 PRINT "SCORE: " S(2); "TO" S(0)

4210 PRINT

4220 RETURN

The code for FTBALL is simple, but it’s difficult to read for a few different

reasons, some of which were due to the design of BASIC at this time.

Different functions for the plays are called by GOTOs and line numbers rather than function names, so you

can’t tell where the program is going unless you go to that line and figure

it out. The line numbers clutter up the visual presentation of the code,

and only the line numbers for lines that are called by the program through

GOTOs or GOSUBs actually provide information. The GOTOs and GOSUBs in this version of FTBALL do indeed result in some

“spaghetti code” in that different plays and results will jump

around to a half-dozen arbitrary lines before resolving. (The later version

in Ahl does away with some of this jumping.) The variables are single

letters, which makes them difficult to understand what they represent. And

in debugging, it is much more difficult to search for Y than Yardage, especially using the

“find” tools available in a modernday editor. There are simple

remarks (REMs) to demarcate different parts

of the program, but they don't explain what it’s doing or where it’s

going.