Abstract

Annotating – understood here as the process in which segments of a text are marked as

belonging to a defined category [Reiter, Willand, and Gius 2020] – can be

seen as a key technique in many disciplines [Macmullen 2005],

especially for working with text in the Humanities [e.g. Unsworth 2000], the

Computational Sciences (e.g. [Sivasothy et al. 2021]; [Doleschal et al. 2022]), and the Digital Humanities [Caria and Mathiak 2019]. In the field of Digital Humanities, annotations of

text are utilized, among other purposes, for the enrichment of a corpus or digital

edition with (linguistic) information (e.g. [Lu 2014]; [Nantke and Schlupkothen 2020]), for close and distant reading methods (e.g.

[Jänicke et al. 2015]), or for machine learning techniques (e.g. [Fiorucci et al. 2020]). Defining categories to shape data has been used in

different text analysis contexts, including the study of toponyms (e.g. [Kyriacopoulou 2019]) and biographical data (e.g. [Aprosio and Tonelli 2015]).

The paper at hand showcases the use of annotations within the Vienna Time Machine

project (2020-2022, PI: Claudia Resch) which aims to connect different knowledge

resources about historical Vienna via Named Entity Recognition (NER). More

specifically, it discusses the challenges and potentials of annotating 18th century

death lists found in the Wien[n]erisches Diarium or

Wiener Zeitung, an early modern newspaper which was

first published in 1703 and has already been (partly) digitized in form of the

so-called DIGITARIUM [Resch and Kampkaspar 2019]: Here, users can access

over 330 high-quality full text issues of the newspaper which contain a number of

different text types, including articles, advertisements and more structured texts,

such as arrival or death lists. The focus of this article lies on the semi-structured

death lists, which do not only appear in almost every issue of the historical Wiener Zeitung, but are also relatively consistent in their

structure and display a high semantic density: Each entry contains detailed

information about a deceased person, such as their name, occupation, place of death,

and age.

Annotating these semi-structured list items opens up multiple possibilities: The

resulting classified data can be used for efficient distant or scalable reading,

quantitative analyses [Nanni, Kümper, and Ponzetto 2016], and as a gold

standard for both rule-based and machine learning NER approaches (e.g. [Jiang, Banchs, and Li 2016]). To reach this goal and as a first step of the

annotation process, the project team conducted a close reading of various death lists

from multiple decades to identify recurrent linguistic patterns and, based hereon, to

develop a first expandable set of categories. This bottom-up approach resulted in

five preliminary categories, namely PERSON, OCCUPATION, PLACE, AGE and

CAUSE-OF-DEATH, which were color-coded [Jänicke et al. 2015] and,

accompanied by annotated examples, documented in the form of annotation guidelines as

intersubjectively applicable and concise as possible. These guidelines were then used

by two researchers familiar with the historic material to annotate a randomly drawn

and temporally distributed sample of 500 death list entries in the browser-based

environment Prodigy (https://prodi.gy). Hereby,

the emphasis was put especially on emerging “challenging” cases, i.e. items

where annotators were in doubt about their choice of category, the exact positioning

of annotations or the necessity to annotate certain text segments at all. Whenever

annotators encountered such ambiguous items, these were collected, grouped and – as a

third step in the annotation process – discussed with an interdisciplinary group of

linguists, historians and prosopographers. Within this collective, a solution for

each group of issues was agreed on and incorporated into the annotation guidelines.

Also, existing categories were revised where necessary. The new, more stable category

system was then again used for a new sequence of annotation and discussion of

ambiguities, resulting in an iterative process where annotation and category

development became intertwined. This approach, explained in the article in more

detail, demonstrates that tagsets are never entirely final, but always depend on

particular knowledge interests and data material and that even the annotation of

inherently semi-structured lists requires continuous critical reflection and

considerable historical and linguistic knowledge.

At the same time, it can be exemplified by this work that it is precisely these

“challenging” cases which carry a great potential for gaining knowledge and

can be considered central to the development of a valid annotation system (cf. [Franken, Koch, and Zinsmeister 2020]).

Introduction

Digital processes and research practices have given new relevance to the formation of

categories for textual analysis, as evidenced by the presence and complexity of the

term

annotation. The annotation of data can be seen as a key technique

in many disciplines [

Macmullen 2005], especially for working with text

in the Humanities (e.g. Unsworth, 2000), the Computational Sciences (e.g. [

Sivasothy et al. 2021]; [

Doleschal et al. 2022]) and

subsequently, the Digital Humanities [

Caria and Mathiak 2019]. Rehm [

Rehm 2020, p. 299] also reaffirms this, stating that the “annotation of textual information is one of the most fundamental

activities in Linguistics and Computational Linguistics including neighbouring

fields such as, among others, Literary Studies, Library Science and Digital

Humanities”.

In the broad field of Digital Humanities, annotations of text are used in

multifaceted ways, as they pose a crucial methodological step for the further

analytical processing of text sources within different analytical procedures [

Franken, Koch, and Zinsmeister 2020]. For example, they allow for the

enrichment of a corpus or digital edition with (linguistic) information (e.g. [

Lu 2014]; [

Nantke and Schlupkothen 2020]), for the use of

close and distant reading methods (e.g. [

Jänicke et al. 2015]), or for

machine learning techniques (e.g. [

Fiorucci et al. 2020]).

Annotation can broadly be defined as the “addition of metadata,

comments, markup, or other information that supplements the original data and

renders it richer or more usable”

[

Flanders and Jannidis 2019, p. 313]. It potentially includes the

assignment of (e.g. descriptive, technical or bibliographical) metadata,

text-structural information, mark-up on the lexical or grammatical level as well as

semantic annotations of varying depth or complexity – depending on the objects and

project goals or research questions [

Lordick et al. 2016, p. 188].

The paper at hand defines annotating as the process in which segments of a text are

marked as belonging to a defined category [

Reiter, Willand, and Gius 2020, p. 329], which will be applied for the analysis of death lists in the 18th

century newspaper

Wien[n]erisches Diarium. In the course

of this paper, we will demonstrate, based on concrete examples, how defining

categories can also be beneficial for the study of toponyms (e.g. [

Kyriacopoulou 2019]; [

Palladino 2021]) and biographical

data (e.g. [

Aprosio and Tonelli 2015]). Especially texts with a high

information-density, such as the lists investigated here, allow for a fruitful

application of annotations, making them a valuable contribution for digital textual

scholarship. However, there is a variety of different obstacles and hurdles to

overcome when annotating (historical) text, which will be described in detail.

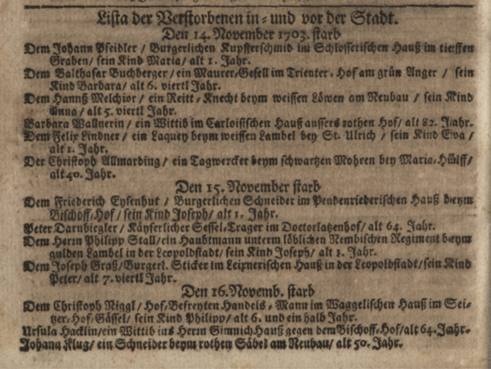

What’s in the news? Historical newspapers as rich knowledge (re)sources

The paper at hand showcases the use of annotations within the Vienna Time Machine

project (2020–2022, PI: Claudia Resch), which aims to connect different knowledge

resources about historical Vienna via Named Entity Recognition (NER). More

specifically, it discusses the challenges and potentials of annotating 18th century

death lists found in the Wien[n]erisches Diarium, an

early modern newspaper which was first published in 1703 and renamed Wiener Zeitung in 1780. For a considerable time period

during the 18th century, it held the undisputed position of being the most important

newspaper within the Habsburg Monarchy. The Diarium was

published twice a week in its first century, was printed in quarto format and

contained between 8 and 40 pages, with a considerable increase in volume towards the

end of the century. The fact that the entire collection as an intact body of issues

published since its inception has been preserved, substantially increases its

significance for scholarship.

The historical

Wiener Zeitung has already been (partly)

digitized in form of the so-called

DIGITARIUM

[1]

[

Resch and Kampkaspar 2019]: here, users can access over 330 high-quality

full-text issues of the newspaper provided as XML/TEI files. As results in

recognizing the German blackletter typeface with traditional OCR software are usually

far from satisfactory, the layout and text recognition relied on the HTR technology

provided by Transkribus. To train an initial model

[2], selected issues

were transcribed completely by hand. In order to create a scientifically sound basis

for a wide range of philological research interests, we preferably avoided

normalising interventions and the historical language was reproduced as close to the

printed original as possible. Those resulting reliable transcriptions then served as

a training and test data set (ground truth) for a new model that was applied to

further issues, whereby the recognition greatly improved over time [

Resch and Kampkaspar 2019, pp. 56–59].

Death lists in the DI(GIT)ARIUM

The historical Wiener Zeitung contains a number of

different text types, including articles, official announcements and advertisements,

but also more structured texts, such as arrival or death lists. The focus of this

article lies on the semi-structured death lists, which do not only appear in almost

every issue of the newspaper, but are also relatively consistent in their structure

and display a high semantic density: sorted by date of death and frequently also by

location (inside vs. outside the city), the persons who died in Vienna since the last

issue of the newspaper are listed.

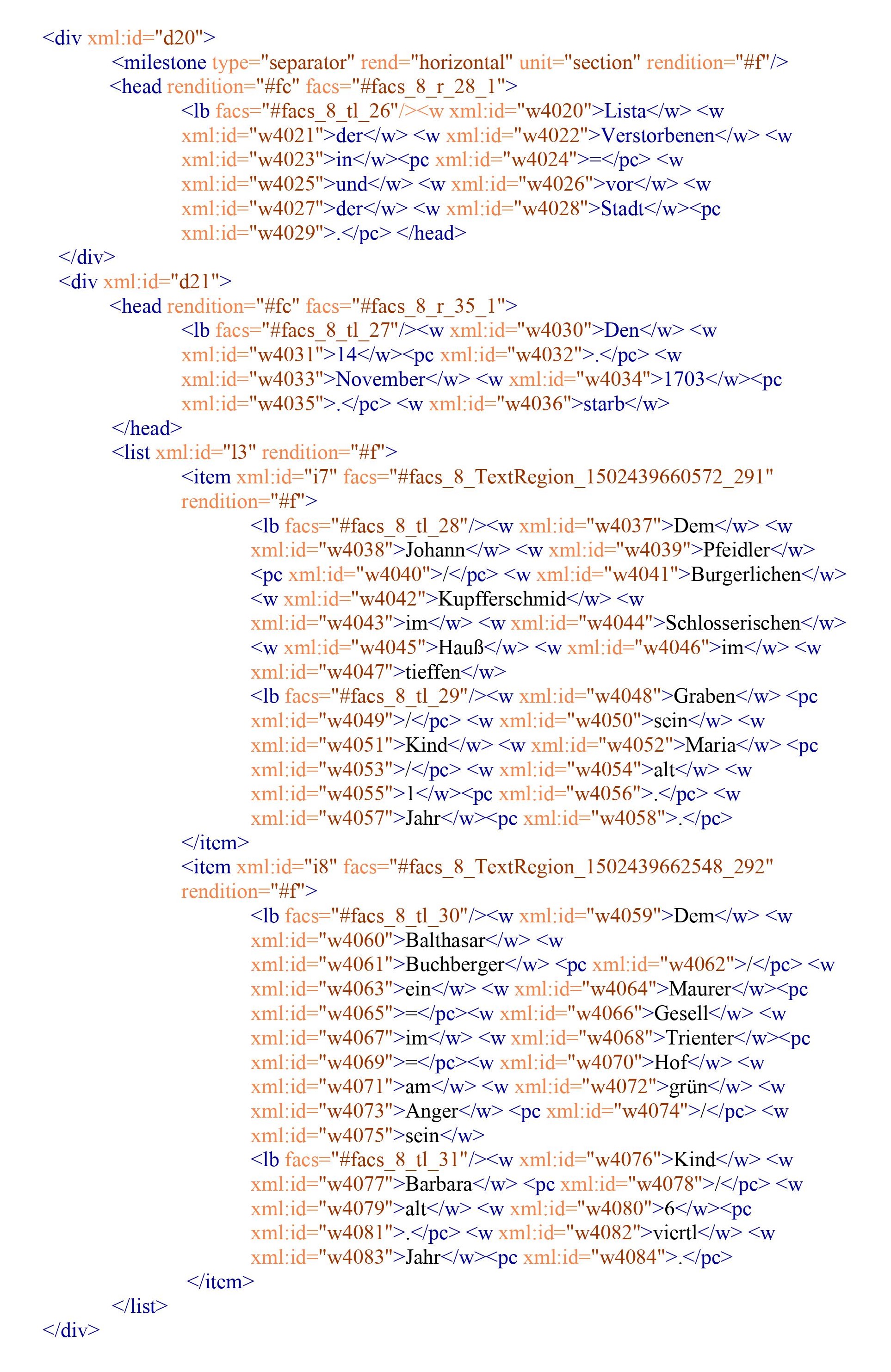

Within the DIGITARIUM, each newspaper issue of the

Diarium was edited using the TEI/P5 guidelines. This

includes the TEI header and several other elements, as for example divisions

(<div>), paragraphs (<p>), words (<w>) and highlighted text, to

distinguish passages or words printed in Antiqua font from its surroundings

(<hi>). For the structural annotation of lists, the <list> element was

used to encode any sequence of items organized as a list. Each distinct item in the

list was then encoded as a distinct <item> element (see TEI Guidelines, Section

3.8). Additionally, (sub-)headings which, in case of the death lists, were used to

group list entries according to time and/or space were encoded through the

<head>-element:

Each of these entries or <item>-elements contains detailed information about a

specific deceased person, for instance their name, occupation, place of death, and

age. Generally speaking, the process of annotating such entities can be analogue or

digital, whereas the latter can again be subdivided in manual, semi-automatic and

fully automatic practices. While analogue annotations serve to organize, structure,

acquire and pass on knowledge, the digital paradigm exceeds these functions, e.g.

allowing for the observation of patterns, further processing of the annotations, as

well as the usage of large amounts of data [

Rapp 2017, pp. 254–255]. At the same time, especially when processing larger (historical) amounts of data,

it is of central importance that the category formation and annotation process is

well-regulated and adheres to clear guidelines. In the special case of death lists in

historical newspapers such guidelines as well as a category system itself are first

to be developed, as such texts have so far only been considered for individual

studies focusing on selected aspects and/or time spans where no systematic annotation

of the material was carried out (e.g. [

Peller 1920]).

Annotation process

To reach this goal and as a first step of the annotation process, the project

team

[3] conducted a

close reading of various death lists from multiple decades to identify recurrent

linguistic patterns and, based hereon, to develop a first expandable set of

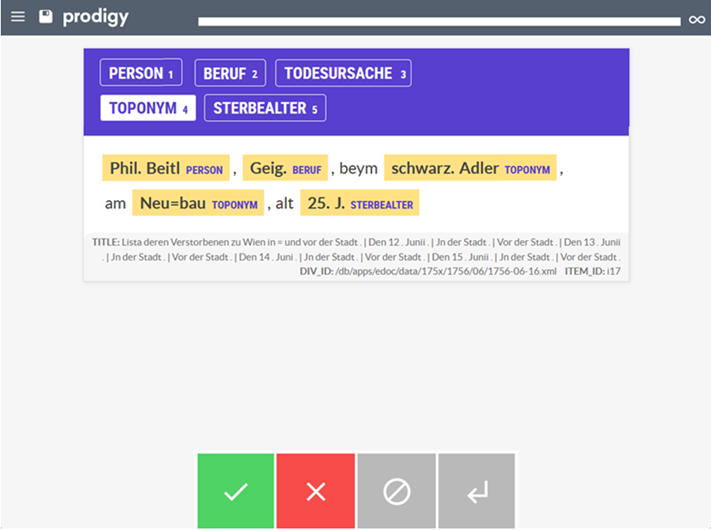

categories. This bottom-up approach resulted in five preliminary categories, namely

PERSON, OCCUPATION, PLACE, CAUSE-OF-DEATH and AGE, as annotated in the exemplary item

below:

-

(1)

Der Johann Rendt / ein Zuckerbacher in Berdronischen Hauß

in Offenloch ist an der Lungelsucht beschaut alt 35. Jahr. (WD

08.08.1703: 9

[4])

PERSON

OCCUPATION

PLACE

CAUSE-OF-DEATH

AGE

The categories derived from the text were color-coded (cf. legend above; [

Jänicke et al. 2015]) and, in combination with annotated examples,

documented in the form of annotation guidelines as intersubjectively applicable and

concise as possible. These guidelines were then used as concrete aids for

decision-making by two researchers familiar with the historic material to annotate a

randomly drawn and temporally distributed sample of 500 death list entries in the

browser-based environment Prodigy (

https://prodi.gy). The software provides annotators with a graphic user

interface, where they are shown one item at a time accompanied by the pre-defined

tagset:

Annotations are made by first choosing a tag through clicking on it and then marking

one or multiple words to which the tag should be assigned. In case of errors or

re-decisions, markings can be easily deleted and redone. Furthermore, Prodigy allows

for unclear items to be omitted and for multiple users to (re-)annotate the same

dataset.

During this annotation process, the emphasis was put especially on emerging

“challenging” cases, i.e. items where annotators were in doubt about their

choice of category, the exact positioning of annotations or the necessity to annotate

certain text segments at all. Whenever annotators encountered such ambiguous items,

these were collected, grouped and – as a third step in the annotation process –

discussed within the interdisciplinary team of philologists, historians and

prosopographers. Within this collective, a solution for each group of issues was

agreed on and incorporated into the annotation guidelines. As a consequence, existing

categories were revised where necessary. The new, more stable and mature category

system was then again used for a new sequence of annotation and discussion of

ambiguities, resulting in an iterative process where annotation and category

development became intertwined. This approach roughly corresponds to Rapp’s [

Rapp 2017, pp. 256–257] basic notion of an annotation process,

which she breaks down into the following five steps: it involves an initial

exploratory data analysis, an initial definition of categories and formulation of

guidelines, the annotation itself, an evaluation, and the repetition of these steps.

Concrete findings that emerged through this process are discussed in the following

sections on the basis of sample items.

PERSON

Since each death list item documents one person that died in- or outside the city

of Vienna, the tag PERSON can be considered fundamental for the annotation task.

It refers to information identifying the individual whose death is detailed,

specifically, their first and/or last name, as given in (2):

- (2) Carl Richter / Burgerl. Schuh=macher / bey dem golden

Lammel / auf der Wieden / alt 44. J. (WD 21.06.1730: 8)

However, not every death list entry follows the prototypical pattern of [first

name] + [last name] given in (2) which provides annotators with a clear conception

of where the PERSON tag should start and end. Instead, items can also, among other

things, involve maternal names (cf. 3), additional titles (cf. 4), and even

unnamed persons (cf. 5). In order to facilitate later disambiguation and to

distinguish items with unknown persons from items missing an annotation tag, we

decided to also subsume such (as well as similar) cases of additional identity

information under the PERSON tag:

- (3) Dem Hern Augustin von Damian, Käyserl. Wasser=Ambts

Gegenhandler / beym rothen Thurn in seim Hauß aussers rothen Hoff / sein

Frau Anna gebohrne von Hoffmann; ist am Schlag=Fluß beschaut / alt 46.

Jahr. (WD 08.08.1703: 8)

- (4) Die (Titl) Fräulein Maria Sibilla Stögerin / von und

zu Ladendorff / im Graff Herbersteinischen Hauß am alten Kühn=Marckt / alt

82. Jahr. (WD 06.02.1706: 9)

- (5) Eine unbek. Weibspers. alt b. 56 J. ist in d. Donau

ertrunken gefunden worden. (WZ 04.06.1796: 13)

Nevertheless, not all issues encountered when annotating could be solved solely by

widening (or narrowing) the scope of the PERSON category. For instance, as example

(3) has already depicted, one death list entry might contain references to more

than one (named) person: As women (e.g. Walburga in 6) and children (e.g. Joseph in 7) were considered less autonomous

than men, no separate entry is recorded under their name; rather, they are

identifiable by the mention of their husband (cf. Karl Wesselly in 6) or father (e.g. Friedrich Eysenhut in

7):

- (6) Dem Karl Wesselly, bürgl. Schneiderm. s. W. Walburga,

alt 39 J. b. St. Ruprecht N. 473. (08.07.1786: 10)

- (7) Dem Friedrich Eysenhut / Burgerlichen Schneider im

Pendenriederischen Hauß beym Bischoff=Hof / sein Kind Joseph / alt 1.

Jahr. (19.11.1703: 8)

It might be argued that one could simply use the sequence of person entities in

each item to discriminate the related (first named) from the deceased person

(second named). However, not all items that include two or more persons

necessarily express a kinship or partnership relation. The entry shown in (8), for

example, accumulates three deceased persons whose only (known) connection is their

same place of death, namely the city hospital:

- (8) Lorentz Gräz / alt 25. Jahr : Mich. Gassenthaler /

alt 21. Jahr : und Rosina Schinnaglin / alt 73. Jahr : alle 3. im dem

Kranken=Haus. (WD 13.03.1732: 7)

Due to such cases as well as the high frequency of items involving more than one

person, an adjustment of the initial tagset was deemed necessary: instead of

assigning the overarching tag PERSON to all (un-)named persons, the category was

split into two separate tags, namely PERSON-DECEASED and PERSON-RELATED. Although

this conceptualisation is currently sufficient for our research interests, further

sub-categories are certainly possible. For instance, depending on the respective

purpose, one could additionally distinguish between first, second and last name,

or between maternal and married name.

OCCUPATION

Another type of personal information included in (almost) all death list entries

is occupational information. Here, in contrast to the previous category, no

additional distinction between the occupation of a deceased person and the

occupation of a relative/spouse needs to be made since given occupation titles

generally refer to male persons:

[5]

- (9) Joh. Wurm, gew. Wirth, alt 36. J. [...] im spanisch. Spit. Mil. Zimm. (WD 20.05.1772: 8)

- (10) Dem Frantz Dietz / burgerl. Fleisch=hackern / s.

Tochter Maria Anna / in seinem h. an der Wien / alt 16. J. (WD

14.07.1734: 7)

In (9) the deceased himself is an innkeeper (Wirth), while in (10) it is the father of the

deceased child whose profession (burgerl.

Fleisch=hacker

“civic butcher”) is mentioned by name. The same principle applies to death

list entries for married women and partly even widows (e.g. Glasermeist. Witw.

“master glazier’s widow”). In this respect, the assignment of OCCUPATION

entities to PERSON entities does not pose an issue. Rather, the difficulty lies in

defining the start and the end point of an OCCUPATION tag since, as it can already

be seen from the examples above, occupational information frequently includes

additional attributive adjectives (e.g. burgerl., gew. [gewester]). Depending on the semantics of

these adjectives, they can either be considered central occupational distinctions

(e.g. Kayserlicher

Schneider

“imperial tailor” vs. Burgerlicher

Schneider

“civic tailor”) or other descriptive supplements (e.g. gewester

“been”).

As another challenge, various textual elements were discovered that cannot be

classified as an occupation, but still reveal essential information about a person

and his or her role in society (e.g. ohne

Condit. [Condition]

“without occupation”, Wittwe

“widow”, verh.

[verheiratet]

“married”, Kind

“child”, armes Mensch

“poor person”, Töchterl

“daughter”, Weib

“wife”). To account for this valuable information as well, a new category and

tag was introduced, namely SOCIAL-ROLE, as annotated in the exemplary items

below:

- (11) Der Anna N. ledigem Menschen / in der Roßau / ihr

Kind Leopold / alt 9. Wochen. (WD 07.02.1711: 9)

- (12) Jos. Gruber, Armer, zur Meerfräule im Lichtenthal,

alt 66. J. (WD 16.05.1772: 7)

PLACE

While information belonging to the categories OCCUPATION and SOCIAL-ROLE is

frequently, but not always present in a death list entry, the place of residence

and/or death is consistently specified. According to our category system, such

toponyms – understood as names for identifiable and thus namable parts of the

earth’s surface (cf. [

Dräger, Heuser, and Prinz 2021, p. V]) – are to

be annotated with the tag PLACE. However, it turned out that an even more precise

working definition of place names must be available for this purpose. For

instance, the prototypical item given in (13), where the life and/or death of the

guardsman Gregori Korber is located near (

bey) the house

grüne[r] Jäger in the urban area of

Lerchenfeld, already raises several

questions:

- (13) Gregori Korber / Guardi=Soldat / bey dem grünen

Jäger im Lerchenfeld / alt 41. J. (WD 13.02.1732: 7)

The first thing to ask is which words are specifically part of the toponym to be

annotated, i.e. whether to include or exclude preceding definite articles from

annotation (dem grünen

Jäger vs. grünen

Jäger). Here, it helps both to compare different texts of the

source material with each other and to include further knowledge resources:

additional list items showcase a frequent merging of preposition and article (e.g.

bey dem > beym)

which makes it impossible to mark only the latter as part of the place name, and

historical city maps (e.g. Steinhausen 1710) refer to houses without articles when

listing them in their legend (e.g. gulden

Löw, Neue Weldt). Thus, both approaches provide arguments for

not regarding articles as part of toponyms.

Secondly, it must be decided whether one (grünen Jäger im Lerchenfeld) or two PLACE tags (grünen Jäger, Lerchenfeld)

should be placed in item (13). As we based the annotation category on the idea of

identifying not places but place names, we chose to go with the latter variant.

This approach also has the advantages that the extracted spatial entities can both

be directly compared and/or linked to other resources and possible spatial

relations are made visible through the presence of multiple PLACE tags within a

single item.

Hence, of the four possible ways to allocate the PLACE tag(s) in (13) which are

shown in (14), version (14b) is considered the “correct” way according to our

annotation guidelines:

- (14)

- a) Gregori Korber / Guardi=Soldat / bey dem grünen

Jäger im Lerchenfeld / alt 41. J.

- b) Gregori Korber / Guardi=Soldat / bey dem grünen

Jäger im Lerchenfeld / alt 41. J.

- c) Gregori Korber / Guardi=Soldat / bey dem grünen

Jäger im Lerchenfeld / alt 41. J.

- d) Gregori Korber / Guardi=Soldat / bey dem grünen

Jäger im Lerchenfeld / alt 41. J.

In addition to this guidance for assigning PLACE tags, further aspects must be

taken into account for when annotating toponyms. On the one hand, within the death

lists, toponyms may appear not only in the form of proper names but also as

appellatives (e.g. Kranken=Haus

“hospital”) and, on the other hand, it may be difficult to distinguish

between place names and place descriptions, as the following item

demonstrates:

- (15) Dem Lud. Schieber, Maur. s. W. Anna Ma. wo die Jgfer

zum Fenst. aussch. am Alsterb. alt 22. J. (WD 05.03.1768: 6)

Although the phrase wo die Jgfer

[Jungfer] zum Fenst. [Fenster] aussch. [ausschaut]

“where the spinster looks out of the window” gives the impression of a place

merely being vaguely described instead of precisely located, it is in fact a

toponym, namely the name of a concrete house. As the Wien Geschichte Wiki (2022),

a historical knowledge platform for Vienna, documents, this house sign stems from

a legend: a girl, who had been looking out for her beloved from the window for

many weeks during the plague in 1410 and 1411, saw his body in the swollen Alsbach

stream flowing past, whereupon she threw herself into the stream and drowned.

Besides such peculiarities of the historical material, the structure of location

information also tends to change over time, as Fischer [

Fischer 2019, pp. 143–144] notes: while early death list items usually contained a

house, street and/or area name, later entries were often more precise and

additionally also included a house number. Accordingly, this can be seen as

another starting point for potentially refining the annotation system for specific

research interests in the future: for instance, one might want to distinguish

between names for different localities (e.g. street, square, district, house) or

provide a specific tag for house numbers.

CAUSE OF DEATH

Besides the aspects already discussed, some (esp. early) death lists also

contained the cause of death for certain persons, which could, among other things,

be a disease (cf. 16), an accident (cf. 17) or a crime (cf. 18):

- (16) Der Anton Huebauer / in Burger=Spital / an

innerlicher Faulung / alt 12. Jahr. (WD 03.01.1722: 8)

- (17) Dem Paul Mattes / Königl. Reit=kn. / s. T. Elisab. /

welche den 9. dieses bey dem Ritter St. Georg in der Josephstadt vom Fenster

herunter gefallen / und gestern darauf gestorben / ist alda vom Königl.

Stadt=Gericht beschauet worden / alt 14. J. (WD 15.09. 1742: 8)

- (18) Joh. Schwimtzky, Gem. vom Löbl. Lasc. Jnf. Reg.

welcher erstochen, und vom K. K. Stadt u. Lgr. in der Alsterg. Casarm

beschaut worden. (WD 05.04.1766: 8)

As indicated by these examples, textual elements that are to be tagged with

CAUSE-OF-DEATH can be given in various grammatical forms; for instance, both nouns

and noun phrases (e.g. innerliche

Fäulung

“internal rot”, Hectica=Fieber

“Hectica fever”) as well as adjectives, verbs and verbal phrases (e.g. erstochen

“stabbed”, vom Fenster herunter

gefallen

“fallen down from the window”) may occur. Furthermore, a new agent is

introduced in this context, namely an inspecting and/or attesting authority who

examines the deceased and officially determines the cause of death, like the Royal

City Court (Königl.

Stadt=Gericht) in (17). Depending on one’s research

interests, such institutional entities could potentially also be assigned a

specific annotation tag in the future. But even if this is not the case, the

list-internal distinction between causes officially autopsied and others only

mentioned of death still very much informs the annotation process, as it has

proven relevant for list items which include both a description of the death

situation (cf. underlinings) and the result of a pathological examination:

- (19) M. Anna Ecksteinin, schutzv. Schneid. Wit. welche

aus dem Bethe gefall. und hierauf gestorb. ist v. k. k

Stadt= u. Landger. am Schlagfl. b. 12. Apost. in der Josephst. beschauet

word. alt 76. J. (WD 16.05.1772: 7)

- (20) Jos. Kayser, Schuhkn. welcher auf eine Schuhale

gefallen und sich verwundet, ist in das

Bäckenh. überbracht, und gestorb. ist v. k. k. Stadt= und Landger. an Brand

besch. word. alt 22. J. (WD 16.05.1772: 7)

For the sake of clarity and with the prospect of automatic analysis of the

annotations, officially autopsied causes of death were given precedence over

unofficial observations and thus annotated solely when present. Only if no

official statement concerning the cause of death was provided in a list entry,

other (descriptive) information about it was marked.

AGE

Last but not least, each death list item found in the Diarium includes the age of the deceased person which is to be marked

with the tag AGE. An advantage here is that no separation in the sense of

PERSON-DECEASED and PERSON-RELATED is necessary, as age statements exclusively

refer to deceased and never to related persons. Nevertheless, challenges still

arise in regard to tagging death lists according to the AGE category. One is the

reappearing question about the limits of what should be annotated; here

concretely, whether the recurrent measurement Jahr

“year” (abbreviated as J.) should be considered as part of the age information and

thus be annotated (cf. 21a) or whether it should be excluded as redundant (cf.

21b):

- (21) a) Johann Daupy / ein Lagey im Gräfl. Walsteinischen

Hauß in der Herrn Gassen / ist an der Lungelsucht beschaut / alt 48. Jahr.

(WD 12.08.1703: 8)

b) Johann Daupy / ein Lagey im Gräfl. Walsteinischen

Hauß in der Herrn Gassen / ist an der Lungelsucht beschaut / alt 48. Jahr.

(WD 12.08.1703: 8)

An answer to this question can be found through further engagement with the

textual material: Although first glances into the death lists give readers the

impression that the age of deceased persons was exclusively counted in years,

closer looks into the historical texts show that a multitude of age measurements

can be attested. Besides cases of half years (e.g. 2. und ein halb Jahr), third years (e.g. 3. und ein drittel Jahr)

and quarter years (e.g. 6. Viertl

J.), also months (e.g. 4. Monat), weeks (e.g. 4 Wochen), days (e.g. 9.

Tag) and even hours (e.g. 2. Stund) were used to

quantify the life span of a person.

For the annotation process, this means that it is of central importance not only

to annotate the respective numerical age specification, but also to include its

verbal unit of measurement. In general, it has proven useful to take into account

verbal supplementary information when annotating age(s). For instance, another

special case that needs to be considered are entries where the age of the deceased

person seems to have been estimated and is thus preceded by bey, bei or b.

“close to, around, approximately”, as in (22) and (23):

- (22) Eine unbekannte Manns=Person / bey der

Schlag=Brucken in der Leopold=Stadt / alt bey 60. J. (WD 11.04.1731:

7)

- (23) Ein Unbekanter armer Mann / in der Roßau / alt bey

40. Jahr. (WD 12.10.1709: 9)

As demonstrated in the two examples above, we decided to also annotate this

lexical marker of age estimation as it makes a viable difference for interpreting

a person’s age. This decision was confirmed by further quantitative and

qualitative analyses of the death lists’ age statements (cf. [

Kirchmair and Rastinger 2021]; [

Rastinger, Kirchmair, and Resch 2022]), which showed that the small word

bei is associated with

the socio-demographic characteristics of the deceased: especially when documented

persons were unknown and/or poor, their age needed to be estimated.

Possibilities and an exemplary application scenario

The preceding considerations and reflections on each category document that a

reliable annotation of our research data is complex and labor-intensive. However, it

should be emphasized that the annotation of precisely these semi-structured list

entries is also a rewarding task: ultimately, the annotations make the inherent

structure of the texts computer-readable, which in turn can become the starting point

for further research.

An essential function of categorising this data is its deeper classification, which

could then be integrated into the existing prototype

DIGITARIUM and in this way enrich the edition. The TEI offers extensive

coding recommendations that would be applicable in the case of persons and places.

Another advantage would be the retrievability of already annotated entities, which

could then be searched for specifically, as frequently wished for by users [

Fischer 2019, pp. 149].

Also, especially important seems to be the fact that reliably annotated data sets

(like the one described) can be used as a training set for machine analysis methods.

To use the dataset “as a gold standard for both rule-based and

machine learning NER approaches”

[

Jiang, Banchs, and Li 2016], was at the same time one of the primary

intentions of the annotation project described (cf. [

Resch, Rastinger, and Kirchmair 2022]). If such approaches prove successful,

they can potentially also be applied to other similar texts, e.g. the arrival lists

of the

Wien[n]erisches Diarium (cf. Rastinger, 2022) or

lists in other early modern periodicals.

[6]

Another important application area that should not be underestimated opens up when

thinking about the future of annotation: if it is the case that annotation decisions

will increasingly also be made by artificial intelligence, the definition of sound

categories determined and approved by experts takes on a special significance as such

category systems can increase the probability of valid and consistent annotations.

For instance, when using Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 (

https://openai.com/gpt-4) for NER, users

are given the possibility to state the labels they would like to use for tagging

their texts which then, in turn, heavily influences the quality of the output.

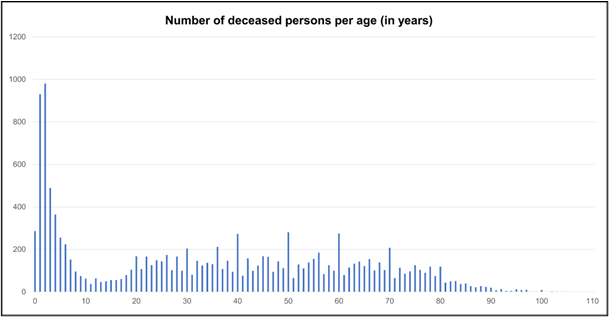

That annotations also enable quantitative analyses [

Nanni, Kümper, and Ponzetto 2016], and make them more transparent, will

finally be shown by an exemplary application scenario. From the multitude of

categories (name, occupation, cause of death etc.), it is the age specifications that

are visualized here as they allow for automatic extraction over the whole dataset.

Before being analyzed on a quantitative level, however, these age specifications had

to be translated from verbal age expressions to numerical values. Hereby, varying

measurements of age (e.g. years, quarter years, days), as well as graphematic

variation (e.g. “quarter years” as

Vierdtel Jahr versus

Viertel=Jahr versus

Viertl J.), needed to be taken into account. Also, the age

expressions could be given in a half-verbal manner which requires high historical

knowledge, as their conversion to numbers diverges from contemporary expectations

multiple times. For example,

dritthalb

Jahr

“three half years” must be translated to 2.5 (i.e. 3 minus 0.5) years instead of

being interpreted as 3.5 (i.e. 3 plus 0.5) years. Through such extensive data

preparation, the verbal age expressions of 13.084 list items were converted to a

numerical form and visualized in the graph below, where the age span of the deceased

in the death lists ranges from two hours to 109 years.

As shown in the plot, the child mortality in the 18th century can be considered to be

very high and, in reality, might have been even higher, as, according to Peller [

Peller 1920, p. 229], stillborn children and children in the first

year of life are often not included in the death lists. While child deaths seem to be

very common during this time period, cases of centenarians can be considered to be

relatively rare, since only 20 of them could be observed in our data. What seems to

be striking are the spikes at round numbers such as 30, 40 or 50. This phenomenon is

already discussed by an academic in the 18th century, namely by Süßmilch [

Süßmilch 1761, p. 362–363], who clarifies that those spikes must

not be interpreted as more people dying at a round age, but rather as an artefact of

a preference for round ages divisible by ten. Stolberg [

Stolberg 2007, p. 50] also links these spikes to socio-cultural circumstances and infers

that the division of life into decades seems to have determined the subjective

experience of the course of life. As this exemplary use case highlights, annotations

of the death lists can be deployed very fruitfully for the investigation of mortality

in the 18th century. However, contextual knowledge is very much needed for

interpreting the results.

Findings and Conclusion

Based on the examples and the application scenario discussed, it has become clear

that the annotation of seemingly simple and short list entries can by no means be

considered a trivial task. Annotating these texts requires specific knowledge and

great familiarity with the source, including an overview of the time period and

knowledge of the early modern newspaper landscape. A hurdle that should not be

underestimated arises from the fact that we are dealing with a level of language that

is remote in time today, and therefore we cannot always rely on our natural sense of

language and judgment. In addition to the graphematic variation, which was not at all

uncommon at the time, there are abbreviations that have become increasingly frequent

over the course of the century, which make text comprehension more difficult and (as

in the next example) must be correctly resolved.

- (24) Dem Phil. [Philip] Noe, Barb.

[Barbier] s. [sein] W.

[Weib] Cath. [Catharina] Nro.

[Numero] 116. nächst der Mariahilferlin.

[Mariahilferlinie] alt 40. J. [Jahre] (WD 09.06.1773:

8)

In order to understand these abbreviations, not only linguistic-historical knowledge

is needed, but also topographical knowledge of Vienna in the 18th century – the

letter

M, for example, can

stand for

Markt

“market”,

"Mühle

“mill” or more meanings.

[7] In all cases of doubt, it is advisable

to compare the respective entry with others or to search for similar (complete) forms

that have already occurred and from which the abbreviations can be derived. For the

recognition of professions that no longer exist today, the annotators will also need

profound historical-cultural knowledge, otherwise it can happen that an occupation

(such as

Viehmayr in the

following example) is misinterpreted as a personal name.

- (25) Elis. Heimbergerin, Viehmayrs Wit. alt 70 J zu

Margareth. N. 26.

In the course of the annotation process and the intensive effort to form tangible

categories, it has become apparent that our understanding of the death lists and

their entities has deepened increasingly. The initial five categories soon became

insufficient to adequately describe the lists. The expansion of the original five to

seven descriptive categories, namely PERSON-DECEASED, PERSON-RELATED, OCCUPATION,

SOCIAL-ROLE, PLACE, CAUSE-OF-DEATH, and AGE, can therefore also be seen as a

consequence of a growing comprehension and our competence to make increasingly

accurate discernments about the texts analysed. If the annotation process is compared

to a spiral cycle (schematically illustrated in [

Lemnitzer and Zinsmeister 2015, p. 103]) or to an extended hermeneutic

circle (cf. [

Bögel et al. 2015, p. 124]), this annotation cycle can

theoretically be understood as open-ended.

[8]

With this in mind, it is even more important that tools are developed that support

undogmatic annotation and provide users with the possibility to modify existing as

well as "create" new tags even during the annotation process (such as CATMA (

https://catma.de), MAXQDA (

https://maxqda.com) or Annotation Studio (

https://www.annotationstudio.org), so that researchers can dynamically adapt

their tagset when they identify limitations and/or contradictions in their initial

assumptions.

In practice, these open and flexible annotation cycles, where tagsets are never

entirely final, are not seldom confronted with a project reality whose reporting does

not tolerate any postponement or provisionality, but often requires quick decisions.

It is therefore all the more important to allow sufficient time for annotation

processes and also to plan for iterative phases of analysis, discussion and

evaluation. The experience shows that it is worth investing more effort and time in

this phase of the investigation, since it is often precisely through this continuous

critical reflection that new insights into the data material are gained. Last but not

least, a reliable system of categories with well-considered annotations can spark off

a whole new range of questions and ideally has the potential to become a springboard

for further research.

Tools and Websites mentioned

Austrian National Library 2022 Austrian National Library.

(2022) ANNO. Available at

https://anno.onb.ac.at (Accessed: 01 December 2022)

Explosion 2017 Explosion. (2017) Prodigy. Available

at

https://prodi.gy (Accessed: 02 December

2022).

Gius et al. 2022 Gius, E., Meister, J. C., Meister,

M., Petris, M., Bruck, C. Jacke, J. Schumacher, M., Gerstorfer, D., Flüh, M., and

Horstmann, J. (2022) CATMA 6 (Version 6.5). Available at

https://catma.de (Accessed: 02 December

2022).

VERBI Software 2021 VERBI Software. (2021) MAXQDA 2022.

Available at

https://maxqda.com (Accessed: 01

December 2022).

Works Cited

Aprosio and Tonelli 2015 Aprosio, A. P., and

Tonelli, S. (2015) “Recognizing Biographical Sections in

Wikipedia”, Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on

Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 811–816. {Available

at: DOI: 10.18653/v1/D15-1095.}

Bögel et al. 2015 Bögel, T., Gertz, M., Gius, E.,

Jacke, J., Meister, J. C., Petris, M., and Strötgen, J. (2015) “Gleiche Textdaten, unterschiedliche Erkenntnisziele? Zum Potential vermeintlich

widersprüchlicher Zugänge zu Textanalyse”,

Proceedings DHd 2015 Von Daten zu Erkenntnissen.

Book of Abstracts, pp. 119–127. {Available at:

http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:dhd2015.abstracts-vortraege (Accessed: 02

December 2022).}

Caria and Mathiak 2019 Caria, F. and Mathiak,

B. (2019) “Annotation in Digital Humanities” in Kremers,

H. (ed.), Digital cultural heritage. {1st edn.} Cham:

Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 39–50. {Available at: DOI:

10.1007/978-3-030-15200-0_3. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Doleschal et al. 2022 Doleschal, J.,

Kimelfield, B., Martens, W., and Peterfreund, L. (2022) “Weight

Annotation in Information Extraction”, Logical Methods

in Computer Science, 18(1), pp. 1–18. {Available at: DOI:

10.46298/lmcs-18(1:21)2022. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Dräger, Heuser, and Prinz 2021 Dräger,

K., Heuser, R., and Prinz, M. (2021) “Vorwort” in Dräger,

K., Heuser, R., and Prinz, M. (ed.): Toponyme.

Standortbestimmung und Perspektiven. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter

(Germanistische Linguistik 326), pp. V–VIII.

Fiorucci et al. 2020 Fiorucci, M.,

Khoroshiltseva, M., Pontil, M., Traviglia, A., Del Blue, A., and James, S. (2020)

“Machine Learning for Cultural Heritage: A Survey”,

Pattern Recognition Letters, 133, pp. 102–108.

{Available at: DOI: 10.1016/j.patrec.2020.02.017. (Accessed: 01 December

2022).}

Fischer 2019 Fischer, N. (2019) “Von Orten im Wien[n]erischen Diarium. Anmerkungen zu den Voraussetzungen einer

Annotation von Ortsnamen”, Wiener

Geschichtsblätter, 74(2), pp. 137–149.

Flanders and Jannidis 2019 Flanders, J.,

and Jannidis, F. (2019) The Shape of Data in the Digital

Humanities. Modeling Texts and Text-based Resources. {1. edn.} London, New

York: Routledge.

Franken, Koch, and Zinsmeister 2020 Franken, L., Koch, G., and Zinsmeister, H. (2020) “Annotationen

als Instrument der Strukturierung” in Nantke, J., and Schlupkothen, F.

(ed.), Annotations in Scholarly Editions and Research.

Functions, Differentiation, Systematization. {1. edn.} Berlin, Boston: De

Gruyter, pp. 89–108. {Available at: DOI: 10.1515/9783110689112-005. (Accessed: 01

December 2022).}

Ide and Pustejovsky 2017 Ide, N., and

Pustejovsky, J. (ed). (2017) Handbook of Linguistic

Annotation. {1. edn.} Dordrecht: Springer Dordrecht.

Jiang, Banchs, and Li 2016 Jiang, R., Banchs,

R. E., and Li, H. (2016) “Evaluating and Combining Named Entity

Recognition Systems”, Proceedings of the Sixth Named

Entity Workshop, pp. 21–27. {Available at: DOI: 10.18653/v1/W16-2703.

(Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Jänicke et al. 2015 Jänicke, S., Franzini, G.,

Cheema, M. F., and Scheuermann, G. (2015) “On Close and Distant

Reading in Digital Humanities: A Survey and Future Challenges”, Proceedings of EuroVis — STARs, pp. 83–103. {Available at:

DOI: 10.2312/eurovisstar.20151113. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Kirchmair and Rastinger 2021 Kirchmair,

T., and Rastinger, N. C. (2021) “Corpus-based insights into

discourses of age in the 18th century. A mixed methods approach using the

obituaries of the

Wien[n]erisches Diarium as a

starting point.” Workshop “Zwischen Äußerungen und

Zahlen. Korpuslinguistische Zugänge zu Diskursen”, Austrian Academy of

Sciences and University of Vienna, 05.11.2021. {Available at:

https://disko.dioe.at/poster-kirchmair-rastinger (Accessed: 01 December

2022).}

Kyriacopoulou 2019 Kyriacopoulou, T.,

Martineau, C., and Vartampetian, M. (2019) “Extraction and

annotation of ‘location names’”, Infotheca –

Journal for Digital Humanities, 19(2), pp. 7–25. {Avaiable at: DOI:

10.18485/infotheca.2019.19.2.1. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Lemnitzer and Zinsmeister 2015 Lemnitzer, L., and Zinsmeister, H. (2015) Korpuslinguistik.

Eine Einführung. {3rd edn.} Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto.

Lordick et al. 2016 Lordick, H., Becker, R.,

Bender, M., Borek, L., Hastik, C., Kollatz, T., Mache, B., Rapp, A., Reiche, R. and

Walkowski, N. (2016). “Digitale Annotationen in der

geisteswissenschaftlichen Praxis.”

Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 40(2), 186-199.

Lu 2014 Lu, X. (2014) Computational

Methods for Corpus Annotation and Analysis. {1st edn.} Dordrecht: Springer

Dordrecht.

Macmullen 2005 Macmullen, W. J. (2005) “Annotation as Process, Thing, and Knowledge: Multi-domain studies of

structured data annotation”, SILS Technical Report

TR-2005-02, 6. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, School of

Information and Library Science. Technical Report series.

Nanni, Kümper, and Ponzetto 2016 Nanni, F., Kümper, M., and Ponzetto, S. P. (2016) “Semi-supervised Textual Analysis and Historical Research Helping Each Other: Some

Thoughts and Observations”, International Journal of

Humanities and Arts Computing, 10(1), pp. 63–77. {Available at: DOI:

10.3366/ijhac.2016.0160. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Nantke and Schlupkothen 2020 Nantke, J.,

and Schlupkothen, F. (ed.) (2020) Annotations in Scholarly

Editions and Research. Functions, Differentiation, Systematization.

Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. {Available at: DOI: 10.1515/9783110689112. (Accessed: 01

December 2022).}

Palladino 2021 Palladino, C. (2021) “Representing Places in Texts: A Spatial Investigation into

Agathemerus’ Sketch of Geography”, International

Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 15(1–2), pp. 33–59. {Available

at: DOI: 10.3366/ijhac.2021.0261. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Peller 1920 Peller, S. (1920) “Zur

Kenntnis der städtischen Mortalität im 18. Jahrhundert mit besonderer

Berücksichtigung der Säuglings- und Tuberkulosesterblichkeit (Wien zur Zeit der

ersten Volkszählung)”, Zeitschrift für Hygiene und

Infektionskrankheiten, 90, pp. 227–262. {Available at: DOI:

10.1007/bf02184229. (Accessed: 01 December 2022).}

Rapp 2017 Rapp, A. (2017) “Manuelle

und automatische Annotation” in Jannidis, F., Kohle, H., and Rehbein, M.

(ed.) Digital Humanities. Eine Einführung {1. edn.}

Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, pp. 253–267.

Rastinger, Kirchmair, and Resch 2022 Rastinger, N. C., Kirchmair, T., and

Resch, C. (2022) “Praising highly aged persons and banning the

mourning of child deaths: age discourses in an 18th century German newspaper

corpus”, 6th Corpora & Discourse International

Conference (CADS), Bertinoro 26.08.2022.

Rehm 2020 Rehm, G. (2020) “Observations on Annotations” in Nantke, J., and Schlupkothen, F. (ed.),

Annotations in Scholarly Editions and Research. Functions,

Differentiation, Systematization. De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston (2020), pp.

299–323. {Available at: DOI: 10.1515/9783110689112-015. (Accessed: 02 December

2022).}

Reiter, Willand, and Gius 2020 Reiter,

N., Willand, M., and Gius, E. (2020) “Die Erstellung von

Annotationsrichtlinien als Community-Aufgabe für die Digitalen

Geisteswissenschaften” in Nantke, J., and Schlupkothen, F. (ed.), Annotations in Scholarly Editions and Research. Functions,

Differentiation, Systematization. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 325–350.

{Available at: DOI: 10.1515/9783110689112-015 (Accessed: 02 December 2022).}

Resch and Kampkaspar 2019 Resch, C., and

Kampkaspar, D. (2019) “DIGITARIUM – Unlocking the Treasure Trove

of 18th-Century Newspapers for Digital Times” in Wallnig, T., Romberg, M.,

and Weis, J. (ed.) Digital Eighteenth Century: Central European

Perspectives. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau, pp. 49–64.

Resch, Rastinger, and Kirchmair 2022 Resch, C. Rastinger, N. C., and

Kirchmair, T. (2022) “Die historische Wiener

Zeitung und ihre Sterbelisten als Fundament einer Vienna Time Machine.

Digitale Ansätze zur automatischen Identifikation von Toponymen”, Wiener Digitale Revue, 4. {Available at:

DOI:10.25365/wdr-04-03-04. (Accessed: 02 December 2022).}

Sivasothy et al. 2021 Sivasothy, S., Barnett,

S., Fernando, N., Vasa, R., Sinha, R., and Simmons, A. (2021) “Towards a taxonomy for annotation of data science experiment

repositories”, IEEE 21st International Working Conference

on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation (SCAM), Luxembourg: IEEE Computer

Society Conference Publishing Services (CPS), pp. 76–80. {Available at: DOI:

10.1109/SCAM52516.2021.00018. (Accessed: 02 December 2022).}

Stolberg 2007 Stolberg, M. (2007) “Zeit und Leib in der medikalen Kultur der Frühen Neuzeit” in

Brendecke, A., Fuchs, R.-P., and Koller, E. (ed.), Die Autorität

der Zeit in der Frühen Neuzeit. Berlin: LIT, pp. 49–68.

Süßmilch 1761 Süßmilch, J. P. (1761) Die göttliche Ordnung in den Veränderungen des menschlichen

Geschlechts aus der Geburt, dem Tode und der Fortpflanzung desselben. Erster Theil

worin die Regeln der Ordnung bewiesen werden […]. Zwote und ganz umgearbeitete

Ausgabe. Berlin: Buchhandlung der Realschule.