2023

Volume 17 Number 3

Abstract

The case study is based on student annotations from a class on “Digital Methods in Literary Studies” taught in the English Studies / English Literatures and Cultures programme at Tübingen University. The annotation task consisted in tagging the ambiguous modality of must in Jane Austen’s novel Emma (1816). The article, in a first step, presents how the criteria for annotation task were developed on the basis of a close reading of the novel; these evolved into annotation guidelines which were then translated into tag sets for two annotation tools: CATMA and CorefAnnotator. The overall results of the annotation process are discussed, with a particular focus on the difficulties that emerged as well as (patterns of) mistakes and misconceptions across the groups and individual annotators. This approach will yield insights into challenges when annotating with a group in a teaching context as well as foreground conceptual difficulties when it comes to annotating complex phenomena in literary texts.

1. Introduction

In the following, we will present a case study based on student annotations from a class on “Digital Methods in Literary Studies” taught in the English Studies / English Literatures and Cultures programme at Tübingen University.

[1] The annotation task consisted in tagging the ambiguous modality of

must in Jane Austen’s novel

Emma (1816). We will first show how the criteria for analysis were developed on the basis of a close reading of the novel; these evolved into annotation guidelines which were then translated into tag sets for two annotation tools: CATMA and CorefAnnotator. We will present the overall results of the annotation process, with a particular focus on the difficulties that emerged as well as (patterns of) mistakes and misconceptions across the groups and individual annotators. This approach will yield insights into challenges when annotating with a group in a teaching context as well as foreground conceptual difficulties when it comes to annotating complex phenomena in literary texts.

The motivation for this case study in a student group was two-fold: the main aim consisted in introducing students to tools and methods of annotation that are applicable in literary analysis. This objective is intricately linked to the problem that literary analysis in general frequently relies very much on intuitions that are difficult to be tested and verified. Category-based approaches and methods from the Digital Humanities may help make the analysis of literary texts more plausible and empirically sound (see also [

Pagel et al. 2020]). It is the markup of texts through annotation in particular that requires phenomenon-based distinctions and clear definitions in order to arrive at (fine-grained) categories of analysis. The starting point is a particular reading experience and text observation that leads to a first hypothesis with regard to the text phenomenon or feature under discussion, from which categories of investigation are then developed. Once these analytical categories are applied in the annotation process, they (potentially) undergo a revision process that then feed into the next round of annotations and so forth (see [

Gius and Jacke 2017]).

The second aim is motivated by a textual phenomenon in Jane Austen’s novel

Emma, namely the ambiguity of voice which is related to an ambiguity of attribution:

[2] this means that, throughout the novel, it often remains unclear whose voice we are being presented with as readers, while there is a defined set of options, e.g. a narrator and a character in the fiction. This is to say that the attribution of voice is not merely underspecified or vague nor without clear referents (see more on this in

section 2 below).

[3] This ambiguity is linked to the ambiguity of the modal

must. The annotation of all instances of

must in the text will hence not only reveal its overall distribution across the novel but, more specifically, indicate how the ambiguity of its modality interacts with ambiguities of voice. The expectation is that this approach will moreover yield results relating to how voice is ambiguous with regard to the narrator and particular characters, e.g. if the ambiguity of voice in the narrator cooccurs more frequently with a particular character than with others. As occurrences of

must are also annotated in direct speech, it will moreover be possible to see if there are characters that use

must more often than others (as well as in which ways). The results of the annotations will then, in turn, feed into the qualitative analysis and interpretation of the novel and its very peculiar narrative techniques.

2. Literary/Narratological Background: Ambiguous Voice in Jane Austen’s Emma

From early on in Jane Austen’s novel, the ambiguity of voice is made obvious: it is unclear who the originating voice of an utterance in the diegetic mode is, i.e. who a proposition can be attributed to. An example is provided in sample 1:

[Sample 1] How was she to bear the change? — It was true that her friend was going only half a mile from them; but Emma was aware that great must be the difference between a Mrs. Weston, only half a mile from them, and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude. She dearly loved her father, but he was no companion for her. He could not meet her in conversation, rational or playful.

[Austen 2012, 6]

The context is as follows: Emma, the protagonist of the novel, introduced as “handsome, clever and rich” [

Austen 2012, 5] in its first sentence, has formed a bond of friendship with her governess Miss Taylor, who, after many years in the Woodhouse household, has married and moved house within the neighbourhood to live with her husband, Mr. Weston. In connection with the opening question of the paragraph – which may be asked by the narrator or be an instance of Free Indirect Discourse (FID)

[4] – it is unclear who thinks that “great must be the difference”: is this Emma or the omniscient narrator with access to her thoughts and feelings – or both?

[5] The question in this passage is an epistemic one and, depending on how we interpret it, we may arrive at different readings: If we attribute it to the narrator’s voice, Emma is objectively suffering from solitude. If we assume that we are presented with Emma’s thoughts, we learn that she regards herself as lonely. The effect based on the author’s strategy is clear: we as readers are supposed to pity her in any case, either because of her feeling or because of the state she factually finds herself in.

These reflections on or by Emma are continued as follows in the opening chapter:

[Sample 2] Her sister, though comparatively but little removed by matrimony, being settled in London, only sixteen miles off, was much beyond her daily reach; and many a long October and November evening must be struggled through at Hartfield, before Christmas brought the next visit […].

[Austen 2012, 6]

Again, it is unclear whether this is a narratorial statement or Emma’s thoughts that are being presented. If we look closely, however, we can see that there is a second ambiguity involved, potentially interacting with the ambiguity of voice: that of the modal verb

must. Generally speaking,

must may be epistemic, deontic or bouletic, i.e. express a fact, an obligation/necessity or a wish (see [

Fintel 2006]). In this instance (sample 2),

must is epistemic as it is a fact that evenings are a struggle in the months of autumn with few visitors before Christmas; but it is also deontic as these evenings have to be struggled through by necessity. This reading is in line with her father having just been presented as being no companion to her; but to avoid interaction with him altogether is not an option either: he “made it

necessary to be cheerful” (

7; emphasis added), as the narrative continues to point out.

Throughout the novel, the “narrative voice that dips in and out of her heroine’s thoughts, fusing Emma’s subjectivity (e.g. in the sense of her limited knowledge) to the narrator’s omniscience” [

Oberman 2009, 2], a narrative device that has frequently been noted and commented on in the literature on Jane Austen.

[6] The concrete linguistic makeup behind this ambiguity of voice has been left widely unobserved, and our hypothesis is that it is intricately linked to the ambiguity of the modal

must. Jane Austen regularly uses this ambiguity, and most famously so in the first sentence of her novel

Pride and Prejudice:

[Sample 3] It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

[Austen 1998, 1]

In this instance, the modal

must is ambiguous, too: a man in possession of a good fortune is generally in want of a wife, he is obliged to be so, and someone may wish this. The question is: whose thoughts are these? If we begin to disambiguate

must here, we come up with different originating voices behind the utterance, with Mrs Bennet being its main originator as her most prominent objective in life is to see her five daughters married as much as the “communal voice” [

Oberman 2009, 9] behind the “truth universally acknowledged.”

To return to Emma.

As there are altogether 571 occurrences of

must in the novel,

[7] it makes sense to use annotation to learn more about these ambiguities and how they are distributed over the novel – as well as how they behave in relation to the various characters and the narrator’s voice.

3. Case Study

The students in the class on digital methods were asked to annotate all instances of

must in Jane Austen’s novel

Emma, on the basis of annotation guidelines provided by their instructor. In what follows, the method will be introduced briefly (

section 3.1), followed by an introduction of the annotation guidelines (

section 3.2) and an analysis (

section 4) of the annotations generated by the students over the course of term.

3.1 Method

The analysis of the ambiguous modality of must in relation to the ambiguity of voice in Jane Austen’s novel is a particularly apt test case for the application of categories for text analysis. Annotation guidelines were developed from a close reading of the novel that were then translated into a tag set which covers all the text features resulting in the various ambiguities under discussion.

The approach is interdisciplinary to begin with and thus exemplifies the complexity of categories in text analysis: in order to succinctly describe the phenomenon this case study is concerned with, linguistic knowhow is needed to conceptualize and use definitions; this approach supports a “precise and detailed analysis of a text, unaffected by arbitrary interpretations or conjectures” [

Bauer et al. 2020, 1]. This approach is not meant to reassert “somewhat simplistic binaries between (objective) analysis and (subjective) interpretations,” as one of the reviewers of this paper put it

[8]; the contrary is the case: with our category-based approach we want to go against the assumption that interpretations are “subjective”. In our understanding, a detailed analysis of the text leads to equally objective interpretations that are text-based.

[9] The case study, based on the link between the ambiguity of modal verbs (a primarily linguistic issue) and of voice (related to narratology) and with the help of tools from Digital Humanities that allow for a quantitative analysis, accordingly had the pedagogical aim to exemplify how an informed analysis may feed into a text-based interpretation. The chosen operationalization can be amplified as well as transferred to other texts (prose fiction) and corpora.

The use of both CATMA and CorefAnnotator was meant to introduce the group to two tools that are available open access and can be applied in teaching, e.g. in a school context, as many of the students are enrolled in the BEd or MEd programmes. We also wanted to find out if the use of a particular tool leads to particular mistakes or is more manageable for students so far unacquainted with digital methods. After a general introduction, students were free to choose the tool they wanted to work with. Six students chose CATMA, divided into two groups of three students each; 13 students worked with CorefAnnotator, divided into three groups of three students each and one group of four.

[10] All groups were asked to annotate at least the first chapter to catch misconceptions in annotating early on in the process; each group was then asked to annotate a particular “package” of chapters within the text:

| Tool |

Group |

Volume |

Chapter |

| CATMA |

A |

1 |

2–18 |

| CATMA |

B |

3 |

6–19 |

| CorefAnnotator |

A |

1 |

2–14 |

| CorefAnnotator |

B |

1/2 |

15–18/1–10 |

| CorefAnnotator |

C |

2/3 |

11–18/1–7 |

| CorefAnnotator |

D |

3 |

8–19 |

Table 1.

Annotated volumes and chapters per group and tool

All members of the groups were supposed to annotate individually at first and to then sit down together to discuss their annotations within their work packages: this was to result in peer discussions to foster a process of understanding in the course of which the annotations would improve and require less discussion as the students went on annotating. Because of the uneven distribution of students over tools, work packages were designed in a way that at least two groups working with CorefAnnotator would (largely) overlap with the CATMA groups in the material they annotated, namely CATMA A with Coref A and B, as well as CATMA B with Coref C and D. The respective annotation groups were asked not only to discuss their individual annotations but agree on a group result to be submitted as their joint annotations for which there was consensus within the group. Unfortunately, this was only done by the groups working with CorefAnnotator: that the students working with CATMA (apparently) never went through this internal negotiation and discussion nor came up with annotations they had agreed on; this, however, only came to light at the end of term when further revisions were no longer possible (see below,

section 4).

3.2 Annotation Guidelines

The textual observations relating to ambiguity as described in section 2 above were translated into annotation guidelines (see

Appendix), with the task to tag and markup all instances of the modal verb

must in the novel, based on the assumption that it may be used ambiguously. The “Preliminaries and Theoretical Background” in the annotation guidelines point to the ambiguous modality of

must, including examples taken from linguistic literature on the topic [

Fintel 2006]; a literary example from Jane Austen’s novel

Pride and Prejudice is also provided (see above, sample 3). The Annotation Guidelines proper were updated in the course of term, based on feedback from the students in their annotation process. They specified, for instance, that all instances of

must in direct speech have to be annotated as well in order to learn more about the overall distribution of the modal verb in the novel as a whole (e.g. the question if it occurs particularly often in the speech of a particular character, but also to see clusters of the modal verb and identify chapters in which it is mentioned more frequently than in others etc.). For characters, the tags “speaker” and “focalizer” were hence introduced to specify the occurrence of

must; as the notion of “focalization” is generally better known to students (in Germany) than “voice,” this term made its way into the annotation guidelines.

[11] By default, the “narrator” should always be tagged as “speaker”.

[12] Students were then asked to follow these steps when annotating:

- Identify / search for all instances of must.

- Read the context of each mention.

- Identify who is speaking or thinking the sentence in which must occurs.

- Annotate who the speaker or focalizer is by marking must and attributing a character as speaker or as focalizer.

- If several options are possible for focalization (e.g. several characters), annotate all of them as in (4).

- Is must epistemic – deontic – bouletic? If several modalities apply, annotate must accordingly.

Another update of the guidelines consisted in the addition of an FAQs section (see below,

Appendix), specifying issues that were addressed in discussions about the annotations. Overall, the approach was one of maximal annotation: if a student or a student group were uncertain as to the meaning of

must, they were asked to annotate all possibilities rather than disambiguate the instance.

4. Analysis

The overall aim was to learn more about how the ambiguous modal

must “behaves” in the novel, i.e. if particular patterns can be identified, especially with regard to the ambiguity of voice. In the course of annotating, however, quite a number of challenges have cropped up as this analysis will show. A major problem was the wrong assumption by some students in the group that annotating a literary work makes reading the novel superfluous. Attributions hence become difficult as contexts within the text remain obscure; put in a more positive way: students have learned about the importance of context in the process.

[13] In a next step, a gold standard would have to be developed to compare the student annotations with, in order to identify all deviations.

In our analysis of the annotations, we have been able to identify technical flaws (

section 4.1) as well as conceptual difficulties (

section 4.2).

4.1 Technical Flaws

As we were interested in finding out whether the work with a particular tool led to specific mistakes, we compared technical flaws between the groups. Particular mistakes indeed cropped up only in the context of either of the tools and could lead, for instance, to a lower inter annotator agreement (IAA)

[14]:

| Level |

Mistake |

CATMA |

CorefAnnotator |

| Annotated word |

Annotation of space (following) |

224 |

0 |

| Annotated word |

Annotation of space (previous) |

14 |

0 |

| Annotated word |

Individual letter left unannotated |

6 |

0 |

| Annotated word |

Annotation of punctuation |

1 |

0 |

| Annotated word |

Wrong word annotated (not must) |

2 |

0 |

| Tags |

Too many tags assigned to a category (duplicates) |

8 |

0 |

| Tags |

Forgotten annotation of a category |

0 |

2 |

| Tags |

Typos in introduction of new tags |

0 |

2 |

| Tags |

Alternative naming of tags |

0 |

191 |

| Total |

|

255 |

195 |

Table 2.

Technical flaws in annotations: a comparison of the tools

While the exclusivity with which the errors occur for one of the tools suggests an explanation in the nature of the tool concerned, we cannot claim this with certainty in

all cases, especially since some errors can rather be attributed to the respective users. This, for example, is apparent for the 224 annotations of spaces following the annotated item in CATMA: a closer look reveals that the majority of these annotations were made by the same student – which, because of this regularity, must be interpreted less as an oversight induced by the tool than an intentional procedure. The complete absence of such errors for the CorefAnnotator, by contrast, can be easily explained: it offers a feature that is activated by default and ignores the annotation of spaces at the outer borders of annotated items. The same applies to non-annotated letters in words as a corresponding feature prevents the annotation of incomplete tokens. In our case, these features automatically protected the annotators of the CorefAnnotator groups from both accidental errors and intentional actions that turned out to be mistakes.

[15]The errors that relate to tags, such as the forgotten annotation of a category, typos in the introduction of new tags for characters that added to the cast in the course of the narrative and alternative names for tags (e.g. “Mr. Knightley” or “Mr Knightley” or “John Knightley”), accumulate conspicuously with the CorefAnnotator, while CATMA shows almost no vulnerability to these types of error in almost inverse exclusivity. This accumulation of errors in tag names may be explained by an intentionally different configuration of the two tools: in CorefAnnotator tags could be added flexibly by the annotators themselves whereas all tags were fixed in CATMA beforehand; this configuration may always be an issue when it comes to using these tools in class: students must apparently be expected to generate mistakes at these points. The evaluations clearly show that – especially for inexperienced annotators – an annotation environment that is as restrictive as possible produces more reliable results. Formal aspects such as these should accordingly be integrated into the annotation guidelines.

4.2 Misconceptions, Misreadings and Challenges

It was agreed that, to get started and become aware of possible pitfalls and difficulties in annotating, all groups would annotate at least chapter one of the novel; in the case of the groups using CorefAnnotator, three of them annotated chapters one to three, while group D did not finally submit their annotations of chapter 1 (without giving a reason). The agreements and divergences across the groups yield insights into conceptual mistakes as well as (partly insurmountable) challenges while annotating; they, however, also point to complexities in the task itself that are revealing with regard to the nature of the phenomenon under consideration.

4.2.1 The First Instance of must: Insights and Hypotheses

The comparison of the annotations for the first instance of must (see above, sample 1) is revealing in respect of the annotating process within the groups. On the basis of this analysis, we eventually decided not to consider the results from the CATMA groups as we saw that the divergences here are mainly based on the wrong application of the annotation guidelines as well as partly inexplicable gaps in the annotations.

| Annotators |

Figure |

Role |

Modality |

| Ca-A Student 1 |

- |

- |

- |

| Ca-A Student 2 |

Narrator |

Focalizer |

epistemic |

| Ca-A Student 3 |

- |

- |

- |

| Ca-B Student 1 |

Narrator |

Focalizer |

epistemic |

| Ca-B Student 2 |

Emma Woodhouse |

Focalizer |

deontic | epistemic |

| Ca-B Student 3 |

Emma Woodhouse

Narrator |

Focalizer

Focalizer |

deontic | epistemic

deontic | epistemic |

Table 3.

Annotations for the first instance of

must by the CATMA groups

It becomes obvious that two students did not annotate must in this instance at all. We do not know if this was because of an oversight (despite the advice to use the search function) or for another reason. We can also see that the remaining students did not take the ambiguity of the figure uttering must into account: only student 3 from group B saw that. But then, all students ignored the default rule that the narrator is always given the role of “speaker.”

A comparison of the annotations provided by those three CorefAnnotator groups that submitted their annotations for the first chapter and sample 1, by contrast, helps develop a few hypotheses as to the difficulties in annotating the ambiguity of voice and

must in the novel:

| Annotators |

Figure |

Role |

Modality |

| Coref-A |

Emma Woodhouse

Narrator |

Focalizer

Speaker |

deontic

epistemic |

| Coref-B |

Emma Woodhouse

Narrator |

Focalizer

Speaker |

epistemic

deontic |

| Coref-C |

Emma Woodhouse

Narrator |

Focalizer

Speaker |

deontic | epistemic

deontic | epistemic |

Table 4.

Annotations for the first instance of must by the CorefAnnotator groups

All groups agree in their attribution of the figures and roles of the instance of

must: both Emma Woodhouse and the Narrator are possible originators of the utterance. The divergence sets in with the modality of must for each of them: groups A and B only attributed one modality to Emma and the Narrator but differed with regard to the attribution as either deontic or epistemic, whereas group C attributed both to each of the speakers. If we go back to the text passage, we can analyse this instance in more detail:

How was she to bear the change? — It was true that her friend was going only half a mile from them; but Emma was aware that great must be the difference between a Mrs. Weston, only half a mile from them, and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude. She dearly loved her father, but he was no companion for her. He could not meet her in conversation, rational or playful.

[Austen 2012, 6]

We found earlier that the attribution leads to different readings: the narrator’s voice states that Emma is objectively suffering from solitude; in the case of a presentation of Emma’s thoughts, we learn that she regards herself as lonely. It is obvious that this is neither an expression of a wish (bouletic reading) nor of a necessity (deontic) but of a fact (epistemic). The deontic reading becomes possible, however, with regard to the greatness of the difference between the two identities of Miss Taylor and Mrs. Weston in their respective locations. From Emma’s perspective, this makes sense as a necessary outcome of the change, and the narrator could be ironical in presenting the change as such. This reading makes sense in the context of Emma’s introduction as a character:

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself;

[Austen 2012, 5]

In her view, any change of situation must be great, especially if she cannot have “her own way”; a fact that the narrator ironically takes into account as well. Against this background, one may assume that both readings of must go for both Emma and the narrator. The difficulty in arriving at this rather complicated interpretation is reflected in the varying disambiguations between groups A and B: their readings are merged by group C who identify an ambiguity for both Emma and the narrator. Based on this observation, we assume that the modality of must will prove to be the most difficult annotation task and lead to the greatest variety in annotations across the CorefAnnotator groups. As to the reasons for this difficulty, we can only speculate, but there are some indicators that it is extremely difficult for students to assume multiple meanings for the modal verb that is so much part of our everyday communication.

4.2.2 Mistakes Exclusive to CATMA

Before altogether discarding the CATMA groups (see

section 4.2.1), we went on to compare all annotated instances of

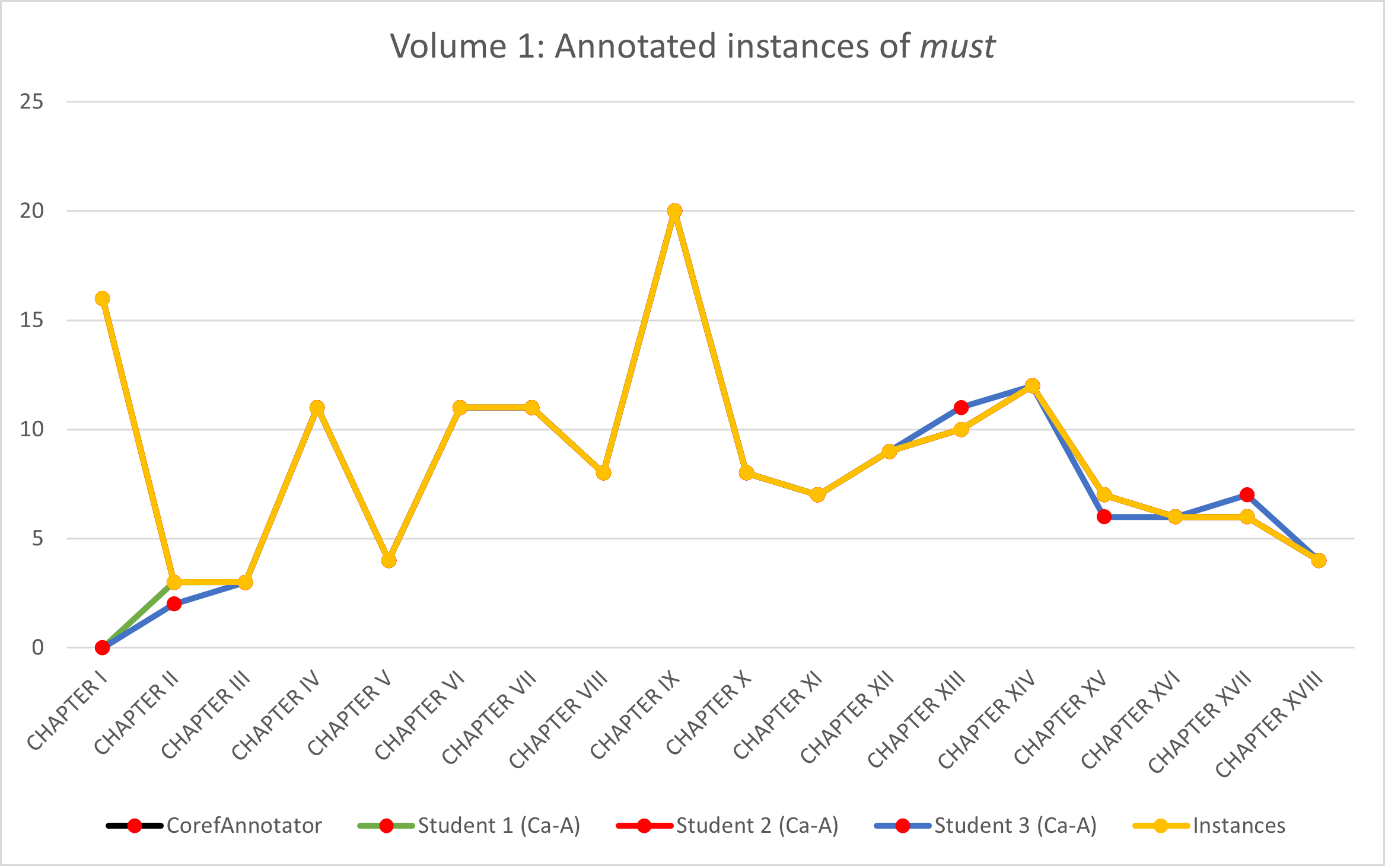

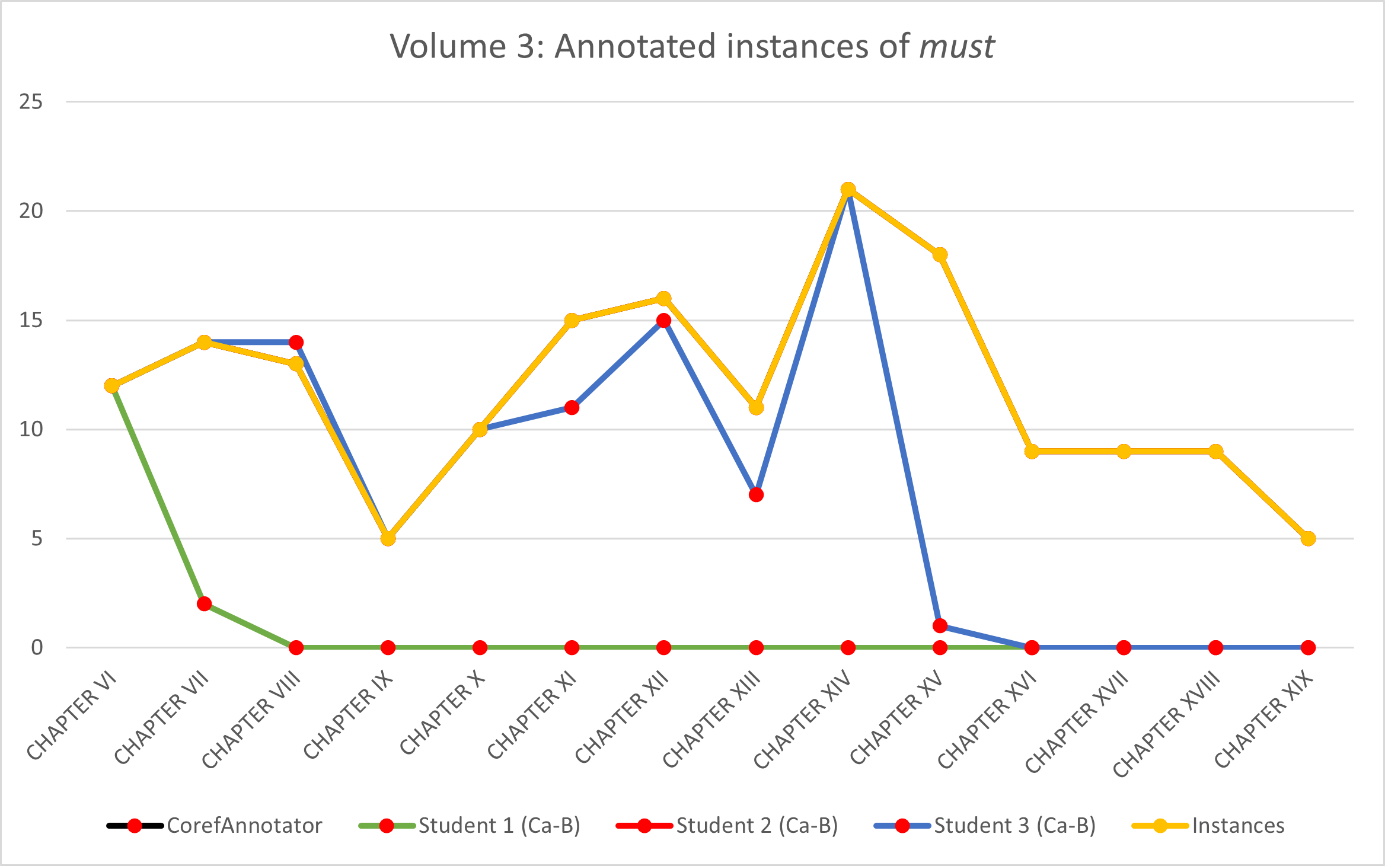

must for all groups who annotated identical chapters within volumes one and three with all actual instances in the novel (see Figures

1 and

2). The golden line represents all instances of

must in all chapters and includes those that were annotated correctly; the individual diverging lines show the number of annotations that do not overlap with the instances.

The annotated chapters of the novel contain altogether 323 mentions of

must. Figure 1 shows that the CorefAnnotator groups

[17] caught all instances of

must, and so did student 2 in CATMA; student 1 in CATMA has one divergence, whereas student 3 has several. In Figure 2, the divergences are more striking: while, once again, the CorefAnnotator group annotated all instances of

must, CATMA student 1 apparently stopped annotating altogether after chapters 6 and 7, and so did student 3 after chapter 16. This was not communicated in any way, and it hence remains unclear whether the task simply appeared to be unmanageable for reasons of content or workload.

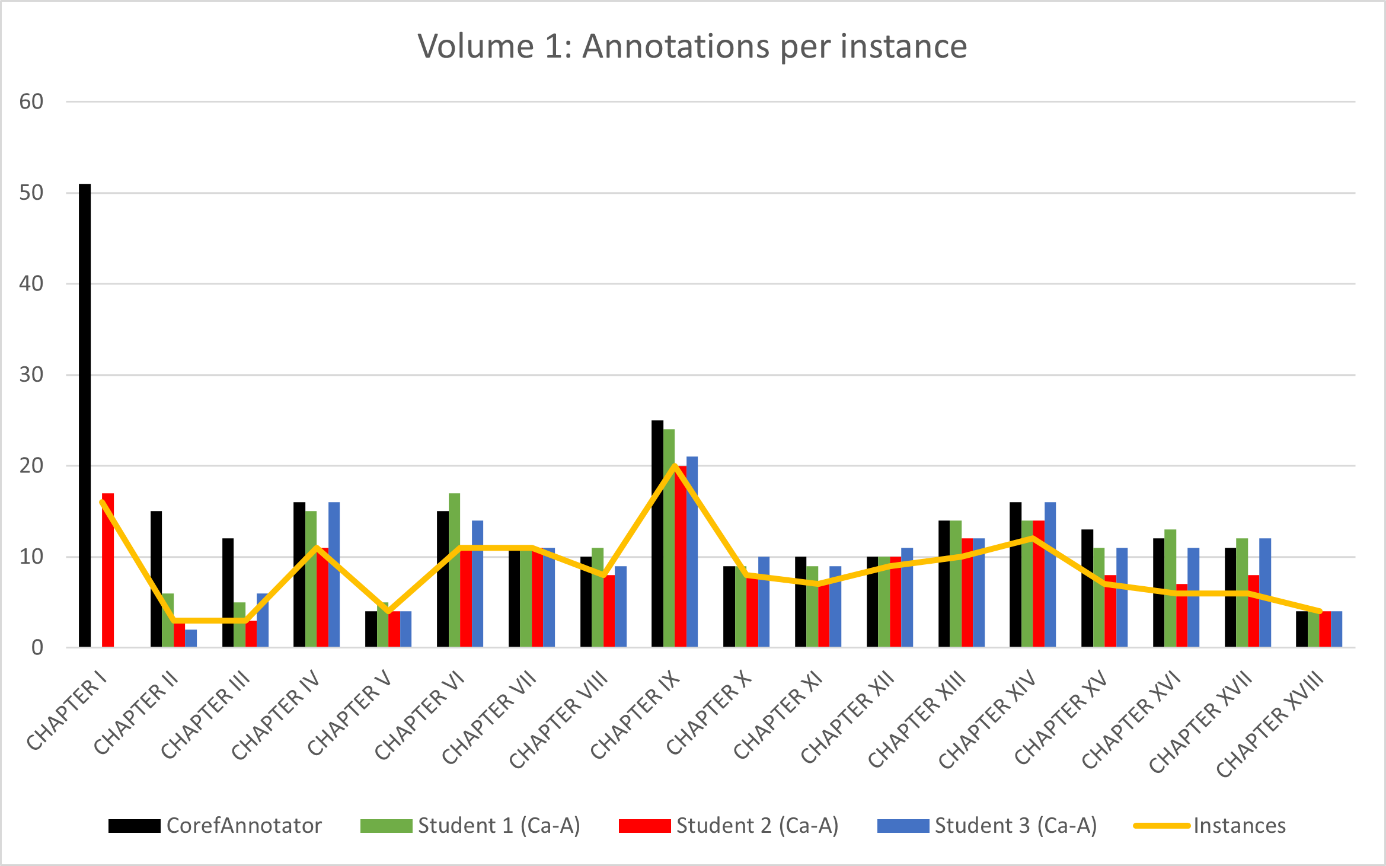

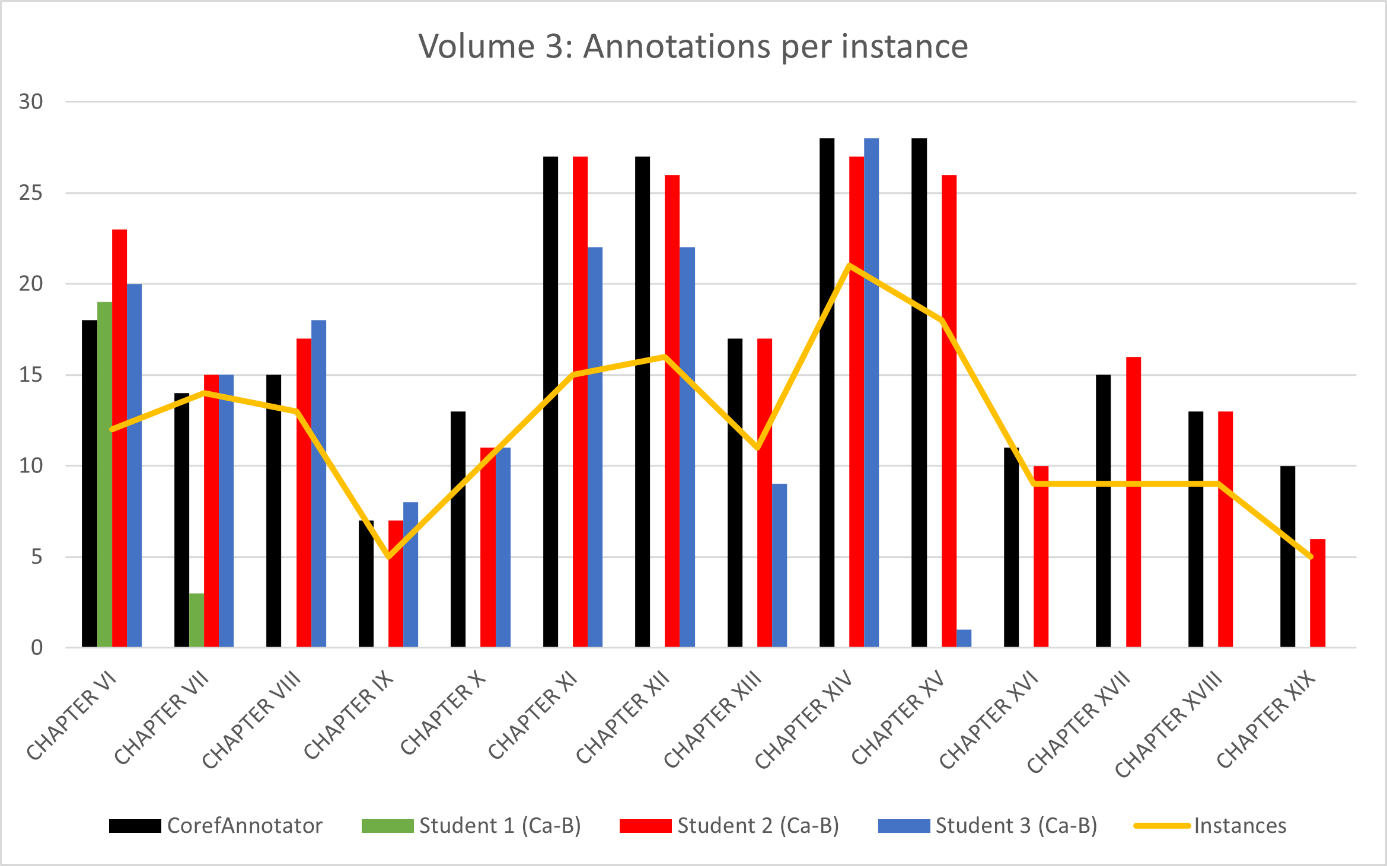

[18]Because of the divergences so far and an apparent tendency within the CATMA groups (see

Table 3) not to annotate ambiguities, we in a next step compared the number of annotations per group and chapter within the first and third volumes. The golden line in

Figure 3 once again shows the actual number of instances (as in Figures

1 and

2 above), and the individual bars indicate annotations of ambiguity as they exceed the number of instances of

must in the text: the double annotations underlying this representation result from the ambiguity of “figure” rather than the ambiguity of modality, i.e. whenever it is unclear in the text whether a character or the narrator is the originator of an utterance, an annotation ensues for each of them. The divergences, once again, allow for a comparison between the groups.

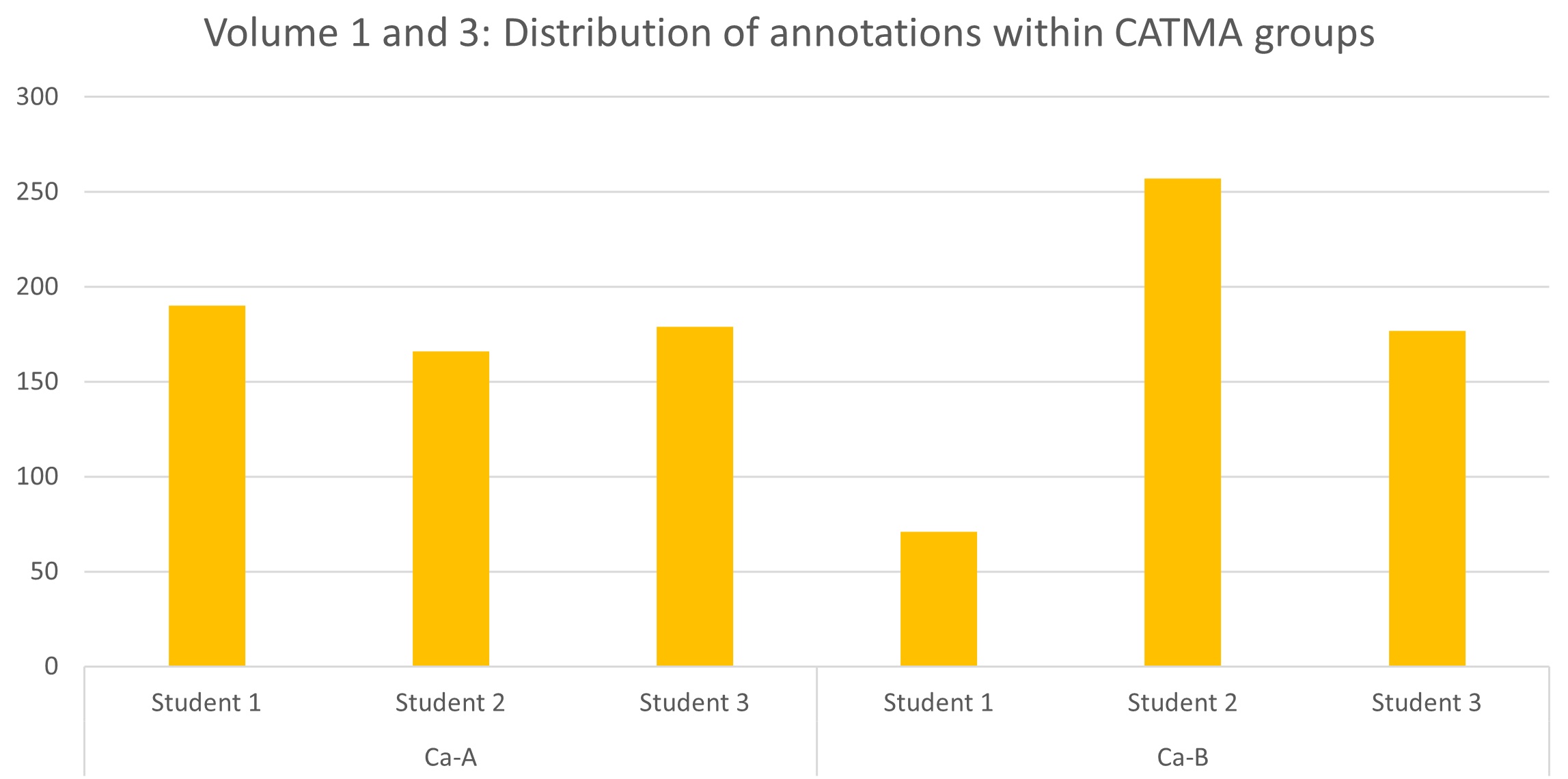

The graph shows that over the 156 mentions of must in the first volume of the novel, the CorefAnnotator group has 258 annotations whereas the students working with CATMA have 190 (Student 1), 166 (Student 2) and 179 (Student 3). This means that they perceived a few ambiguities but far less altogether than the CorefAnnotator group whose annotations are based on in-group discussions and agreement.

The figure for Volume 3 presents a similar result:

Over 167 instances of

must, the CorefAnnotator group identified quite a number of ambiguities, with 243 annotations; as students 1 and 3 in the CATMA group stopped annotating at some point (see

above), there are only 22 annotations for chapters six and seven by student 1 and 154 for student 3; student 2, however, has almost as many annotations as the CorefAnnotator group and overall appears to have worked much more reliably (at least on a quantitative basis).

The following figure summarizes the divergences between the annotations within the group who annotated with CATMA.

This graph shows once more the diverging number of annotations among the students in the CATMA groups over all annotated chapters: it makes evident that no negotiation has taken place within the groups with regard to individual annotations.

4.2.3 Annotating the Ambiguity of Modality

To come back to the first instance of

must in the novel (sample 1) and the annotations as compared in

Table 2 (CorefAnnotator group): overall, the ambiguity of figure and role did not lead to any disagreement between the groups; the major difficulty appeared to be the ambiguity of modality, an impression that came up in class discussions as well. It makes sense to test this hypothesis in light of the data and compare the annotations of the three groups who worked on chapters one to three as a warmup exercise.

In these opening chapters of the novel,

must is mentioned 22 times.

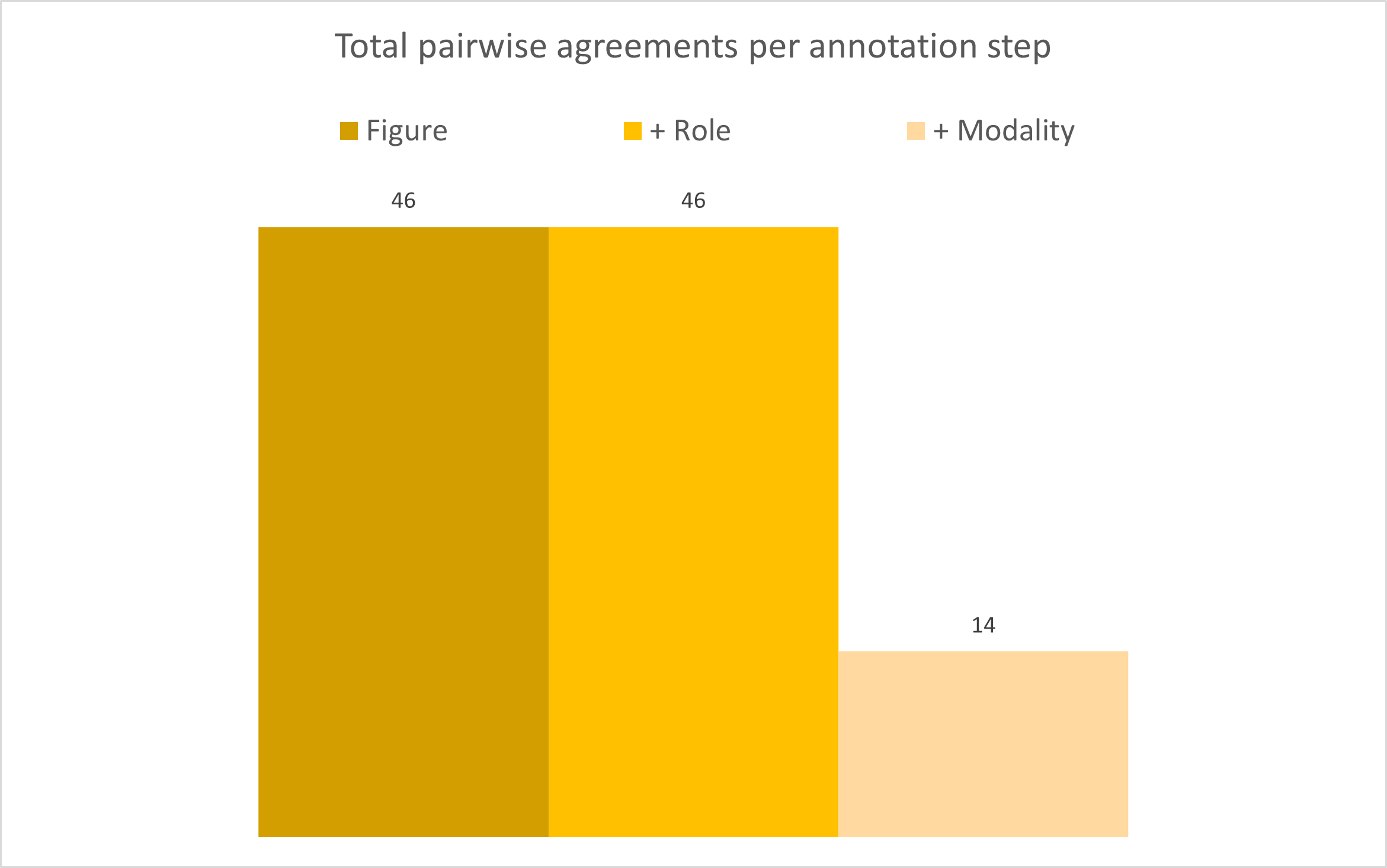

[19] We have calculated the pairwise agreement for the first annotation category “figure” for all instances of

must in the first three chapters and added them up. The pairwise agreement for an instance is “3” if all groups agree on a “figure” (A agrees with B, B agrees with C, A agrees with C) and “1” if at least two of the three groups agree. We then investigated whether and to what extent the pairwise agreement decreases if it is checked for an instance where the three groups agree in “figure”

and “role”, and in a final step in “figure”, “role”

and “modality”.

[20] The maximum pairwise agreement for 22 instances accordingly is 66. The result confirms our assumption that the ambiguity of modality has been most difficult to annotate.

The pairwise agreements for “figure” as well as “figure and role” are comparatively high. It is particularly noteworthy that the inclusion of the “role” annotation category (i.e. the identification of focalizer and speaker) did not result in any loss of agreement over all instances and groups; if there was agreement about the figure in the first place, it remained stable concerning its role as focalizer or speaker. Existing correlations between figures and roles were thus clearly recognised by the students: the narrator is, for example, always identified as “speaker”. The divergence, however, with regard to modality is striking: no inferences are possible, and no (conceptual) links appear to exist between a modality and a figure/role.

While the ambiguity of modality is most difficult to annotate, figure and role attributions are apparently (more) straightforward, potentially so because one can to some extent be derived from the other, and they require a lesser degree of interpretation. This finding is also confirmed when looking at the Fleiss Kappa values for inter annotator agreement (IAA) of each annotation category, especially since figure and role score significantly better with ĸ = 0,67 and ĸ = 0,5 than the category of modality, which is clearly inferior with ĸ = 0,16.

[21]At this point, it makes sense to have a closer look at some of the annotations to see what happens exactly between the groups with regard to the annotation of all categories. One of the following mentions of

must also occurs in the first chapter, when Emma and her father discuss visiting the former governess at her new home:

How often we shall be going to see them and they coming to see us! — We shall be always meeting! We must begin, we must go and pay our wedding-visit very soon

[Austen 2012, 7]

The speaker of this utterance unanimously is Emma – there are no problems whatsoever at annotating this passage accordingly.

| Annotators |

Figure |

Role |

Modality |

| Coref-A |

Emma Woodhouse |

Speaker |

deontic |

| Coref-B |

Emma Woodhouse |

Speaker |

bouletic | deontic | epistemic |

| Coref-C |

Emma Woodhouse |

Speaker |

bouletic | deontic |

Table 5.

Annotations for instance 3 of must by the Coref groups

A difficulty arises, however, once again when it comes to determining the modality of must; given the text and its context, one may argue that group C is correct here: Emma, first and foremost, voices an obligation, even a self-command, based on their social standing (a reading also considered by group A): they “must” make the visit because of that. She clearly also wishes to see her friend soon and as often as possible. To regard her statement as epistemic is more difficult as “begin” denotes a future event and hence cannot count as the perception of a known fact.

A third passage shows yet another difficulty in annotating

must: in chapter two, the reader is introduced to the Westons in more detail and given some background information about Mr. Weston’s prior marriage:

It was now some time since Miss Taylor had begun to influence his schemes; […] He had made his fortune, bought his house, and obtained his wife; and was beginning a new period of existence with every probability of greater happiness than in any yet passed through. He had never been an unhappy man; his own temper had secured him from that, even in his first marriage; but his second must shew him how delightful a well-judging and truly amiable woman could be, […]

[Austen 2012, 13]

It is unclear whether this is merely the narrator reporting Mr. Weston’s thoughts and feelings – or whether we are presented with Mr. Weston’s view in his voice: both are possible and cannot be decided in favour of the one or the other reading. The students, however, very much diverged in their reading of this passage.

| Annotators |

Figure |

Role |

Modality |

| Coref-A |

Mr Weston

Narrator |

Focalizer

Speaker |

bouletic | deontic

epistemic |

| Coref-B |

Narrator |

Speaker |

deontic | epistemic |

| Coref-C |

Mr Weston

Narrator |

Focalizer

Speaker |

deontic | epistemic

epistemic |

Table 6.

Annotations for instance 17 of

must by the CorefAnnotator groups

The table shows that group B did not recognize the ambiguity of the figure here. The other groups diverge with regard to their interpretation of the modalities: they disagree between an epistemic reading of the narrator’s

must in two cases, deontic and epistemic in one case, and they attribute Mr. Weston with deontic and either bouletic or epistemic.

[22] If we look at the text, the narrator may very well also be read as being deontic, but this only works in a meta-narrative reading with her being the law-giver of the narrative in her (slightly ironic) appreciation of Mr. Weston’s thoughts and prospects as well as expectations of married life – and wish him well in a bouletic reading. Mr. Weston himself probably wishes for a happy marriage as much as he counts it for a fact, given the qualities of his wife as he has come to know her, and thinks that he is somewhat entitled to it as he “had never been an unhappy man”. This analysis also foregrounds, once again, that to have read the novel and know about character dispositions is quite obviously indispensable for annotating such phenomena as ambiguity; it also shows that the mere linguistic analysis of the individual word must take into account the larger context, which results in an informed interpretation.

5. Results and Conclusions

The case study aimed, firstly, at exemplifying the process of developing criteria and categories for the study of literary texts that make the analysis more precise, and, secondly, at showing how methods from the Digital Humanities, i.e. annotation, may yield quantitative results that influence close readings and make an interpretation based on a precise analysis empirically valid. In the process, a third objective emerged: to try and test annotation as a teaching and learning tool in a group of advanced students.

The annotation task has proved to generate more challenges than anticipated. This has to do, on the one hand, with technical issues; conceptual flaws, however, turned out to be even more frequent: the annotation of ambiguous modality, even the potential ambiguity of the originators of utterances within the fictional text, transpired to be partly unsurmountable challenges for the student groups. The annotations resulting from the work in the seminar are unfortunately not really of any use for further quantitative analysis: the complexity of the material makes the annotation by expert teams necessary. And yet, the divergencies between the annotations trigger a reflection on the ambiguity of the seemingly-clear-cut modalities and point to an ambiguity of ambiguity: it appears extremely difficult to decide in some of the cases which of the potential modalities are actualized in the context. We have also seen that ambiguous modalities may even result in irony and foreground metanarrative strategies.

The analysis of the annotations thus has been quite revealing in several respects. In the context of digital annotation, they show that the annotation task is challenging: not only have students overlooked instances of

must but they are also prone to careless mistakes, e.g. when direct speech remains undetected.

[23] The negotiations within the groups that used CorefAnnotator led to overall more reliable results than those from the CATMA annotations that were submitted individually. The greatest challenge, however, consisted in wrong attributions: mistakes range from wrong attributions of figure and role to a tendency for disambiguation, in particular with regard to modalities. Roles were wrongly attributed whenever the annotation guidelines were ignored, i.e. when the narrator was given the function of focalizer although this was in fact excluded as an option by the annotation guidelines, with the narrator always counting as speaker by default.

The expectation was that the annotations would yield quantitative results concerning the distribution of the ambiguous modality of must in relation to various characters in the novel, and, in particular, the ambiguity of voice. An analysis of the first chapter of the novel, for instance, has shown that must is mentioned 16 times; and a close reading has revealed that it is used ambiguously almost every time and refers to at least two, sometimes all three modalities. This finding alone, i.e. the clustering of must in the opening chapter, may be regarded as productive with regard to reading the novel as a whole: it almost seems as if Jane Austen was trying to prime her readers and have them watch out for ambiguous modalities. Annotations with a higher IAA would make it possible to visualize the distribution of these ambiguities over direct speech and in relation to focalization. They could moreover show which characters use must most frequently in which communicative contexts, and whose usage of must merges particularly often with that of the narrator to result in ambiguous focalization. At the end of the day, the case study results in quite a number of insights when it comes to didactic and methodological pitfalls, and the clarity of annotation categories turns out to be no guarantor of their correct application. At the same time, annotation may create awareness of categories of analysis and, if pursued diligently, open new paths of literary analysis.

With regard to best practice guidelines when it comes to annotating complex literary phenomena in the classroom, we suggest the following:

- the working methods of students need to be checked regularly, and especially during the early stages of annotating, results need to be checked;

- the importance of working in a team and discussing individual annotations to achieve some IAA needs to be highlighted, particularly in groups that have so far been unacquainted with DH methods and annotation in particular;

- given the complexity of the phenomenon to be annotated in this case study, i.e. the ambiguity of the modal “must”, it would have made sense to start with simple introductory examples as a test study before moving on to the more complex data of Jane Austen’s novel;

- part of the learning process concerns the mere application of the annotation tool. The above-mentioned point, which aims to simplify the task, should create more freedom for students to get to grips with the tool itself, in order to then form routines in its application right from the start of the annotation work. This is especially true for more powerful but (depending on the task: necessarily) not so straightforward tools.

- explain that annotating individual instances of a text does not make reading it as a whole superfluous but that contextual knowledge of the plot and characters is vital to make decisions in the analysis and interpretation.[24]

If students simply lack the motivation or time to pursue a given task diligently, little is to be done, which is probably the only insurmountable problem we face in all teaching contexts. All other issues identified in the course of teaching the class and reflecting on it in this paper may be addressed and will, at least this is what we hope, lead to results that can be used for further research based on the acquired data.

Appendix

The annotation task is to tag and markup all instances of the modal verb “must” in the novel, based on the assumption that it may be used ambiguously.

Preliminaries and Theoretical Background

The ambiguous semantics of the modal verb has been pointed out, e.g., by Fintel: “Modality is a category of linguistic meaning having to do with the expression of possibility and necessity” [

Fintel 2006, 1].

Modal meaning can be distinguished as follows:

-

epistemic: relates to knowledge and “concerns what is possible or necessary given what is known and what the available evidence is” [

Fintel 2006, 2]

e.g. I see people entering the restaurant where I am sitting with umbrellas: “It must be raining.”

-

deontic: relates to duty and “concerns what is possible, necessary, permissible, or obligatory, given a body of law or a set of moral principles or the like” [

Fintel 2006, 2]

e.g. I read hospital regulations: “Visitors must leave by six pm.”

-

bouletic: relates to a wish and “concerns what is possible or necessary, given a person’s desires” [

Fintel 2006, 2]

e.g. a stern father telling his daughter: “You must go to bed in ten minutes.”

These modalities may “overlap”, in which case the modal verb becomes ambiguous. A prominent case of such an ambiguity is the first sentence of Jane Austen’s novel

Pride and Prejudice:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. [Austen 1998, 1]

In this instance, the modal “must” is ambiguous: a man in possession of a good fortune is generally in want of a wife (epistemic), he is obliged to be so (deontic), and someone may wish this (bouletic).

The question is: whose thoughts are these? If we begin to disambiguate “must” here, we come up with different originating voices behind the utterance, with Mrs Bennet being its main originator as her most prominent objective in life is to see her five daughters married as much as the “communal voice” [

Oberman 2009, 9] behind the “truth universally acknowledged.” At the same time, it is the narrator who expresses the general fact; and a third instance, something like the general public, voices an obligation.

The example shows that the ambiguity of must is related to an ambiguity of focalization: several originating instances can be identified, which means that two ambiguities are involved: on the lexical level and on the level of narrative transmission/focalization.

Annotation Guidelines

The aim is to identify all instances of

must and the respective meanings (see above). In order to learn more about its distribution over the novel, not only instances in the narrative transmission by the narrator and in possible focalizing passages will be identified but also those in direct speech; hence the distinction between the tag “speaker” and “focalizer” for characters. As the narrator is the default speaker in diegesis, there is no double tag for him/her but s/he is tagged as “speaker” by default. We also annotate all narrated instances of “must” as ambiguous and attribute a tag for narrator as well as for the character who is the most likely focalizer of the passage (see also below

FAQ 2).

It makes sense to use the search function of the tool in order not to miss out on any instances of “must”.

- Identify / search for all instances of must.

- Read the context of each mention.

- Identify who is speaking or thinking the sentence in which must occurs.

- Annotate who the speaker or focalizer is by marking “must” and attributing a character as speaker or as focalizer.

- If several options are possible for focalization (e.g. several characters), annotate all of them as in (4).

- Is “must” epistemic – deontic – bouletic? If several modalities apply, annotate “must” accordingly.

FAQs

-

In par 92 (CoRef) – “You like Mr. Elton, papa – I must look about for a wife for him” – “must” sounds deontic but Emma probably expresses a wish: how do we decide?

- the point is not to decide in the sense of disambiguation but to identify possibilities: if both meanings are plausible, then both should be annotated in the context

- it is vital to keep in mind that annotations should be based on what is offered in the text: the aim is not disambiguation but to mark the ambiguities

-

How do I know whether it’s the narrator or a focalizing character’s voice in passages of diegesis? See ex. in par 20: “but Emma was aware that great must be the difference…”?

- the description “Emma was aware” shows that we have insight into her thoughts/consciousness, which means we may read this as a passage that focalizes her; at the same time, it is transmitted by the narrator and may be just his or her voice: again, we annotate both, as we do not strive for disambiguation

- as many (if not almost all) narrated instances of “must” can be attributed to a focalizer because of their embedding in verbs like “know”, “felt”, “was aware” etc. or a possible instance of Free Indirect Discourse (see also in ch. 2, par 114: the paragraph beginning with Mr. Weston “He had only himself to please in his choice” could easily be read as FID, which can be seen in the possibility to add “He thought how…”.

-

Can “must” be epistemic if a character says it? See, for example, par 78: “It is impossible that Emma should not miss such a companion,” said Mr. Knightley. “We should not like her so well as we do, sir, if we could suppose it; but she knows how much the marriage is to Miss Taylor’s advantage; she knows how very acceptable it must be, at Miss Taylor’s time of life, to be settled in a home of her own…”

- in this case, all three meanings should be tagged, as this must be Emma’s wish, her obligation as much as a fact

- even though we assume a certain degree of subjectivity in a character’s statement, they may still express a fact

- the case in the example is particularly complicated as Mr. Knightley is suggesting/assuming what Emma (should) think(s); yet, he is still a speaker, and we do not assume Emma to be a focalizer in an instance of direct speech

-

Can the narrator have a wish?

- this is systematically interesting, and we do not assume an involvement of the narrator to a degree that such subjectivity is possible (in the example of Emma!)

Notes

[1] The class was taught in the summer term of 2022 for advanced students. Altogether, nineteen students took part in this seminar, most of them being enrolled in the BA English and American studies, the MA English Literatures and Cultures and the BEd / MEd English; three of the students were enrolled in the BA/MA programme International Literatures.

[2] Parts of the literary background presented in what follows were presented at the conference “Ambiguity Matters”, organized by RTG 1808 “Ambiguity: Production and Perception” at Tübingen University, in a joint paper by Michael Reid and Angelika Zirker on “Ambiguity of Voice: From Mr Knightley to the Green Knight.”

[3] When we speak of voice, in itself a notoriously underspecified term, we refer to whoever speaks or to whom an utterance or thought is attributed in a fictional text. With this notion, we go slightly beyond what is customarily regarded as voice, i.e. the “persona […] behind […] the first-person narrator” [Abrams and Harpham 2015, 287], but rather think of it in terms of the origin(ator) of an utterance or thought, be it on the level of character or narration; in short, “the relationship between a character’s thoughts – his or her internal voice – and the voice of the narrator” [Davidson 2008, 237]. This comparative openness is helpful particularly when it comes to ambiguity, e.g. on the level of character thoughts and speech. The concept of “voice,” especially in the context of ambiguity, has often been linked to Ducrot’s notion of polyphony ([Ducrot 1984]; see also [Waltereit 2006, 63]; and [Bauer 2015, 149]). [4] Oberman refers to Cohn’s term “narrated monologue” [Oberman 2009, 109–10] in the context of Emma and considers the term to be “more specific” than FID (2n2); see also [Pollack-Pelzner 2013, 766]. Bray notes that, in the context of FID, “point of view can be hard to determine and ambiguous” [Bray 2007, 37]. – According to Genette, the explanation is of course that this is a case of (uncertain) focalization. Interestingly, the distinction introduced by Genette between who speaks and who sees does not consider that there may be a difference of voice in FID, where the character’s language is used [Genette 1980, 186]. [5] See, e.g., Oberman who writes: “In third-person narrated novels that dip in and out of the consciousnesses of multiple characters, there are usually moments when it is not easy to know for sure whether the voice we are hearing belongs to the narrator or to a character in the novel” [Oberman 2009, 1]. [6] What is particularly tricky: there may even be an added ambiguity as we do not always know whether the narrator is heterodiegetic or homodiegetic. Does the narrator “create” the characters (and, accordingly, is omniscient), or does the narrator “look” at them (on the basis of her limited knowledge)?

[7] The novel consists of altogether 160,310 words and is structured into three volumes, with 18 chapters in each, volumes one and two, and 19 chapters in volume three.

[8] We would like to thank the reviewer for pointing out this possible misunderstanding.

[10] In hindsight, it may have been more sensible not to leave the choice of the tools to the students but form identical groups for each of the tools to make the analysis more comparable. At the same time, the group division as it stands has resulted in some intriguing insights as well (see below).

[11] The notion of “voice” was not even addressed in more detail because of that. We still think, however, that it makes sense, on some level, to distinguish “voice”, as “an utterance or thought” (see above, note 3) attributed to a character goes beyond Genette’s rather simplistic “who sees,” especially when it comes to ambiguities of voice between characters and the narrator (see also note 11 on this matter).

[12] This follows the view, expressed, for example, by Margolin, that “the term ‘narrator’ designates the inner-textual (textually encoded) highest-level speech position from which the current narrative discourse as a whole originates” ([Margolin 2014, ¶1], emphasis added). [13] There was a number of students who made this wrong assumption, especially in the CATMA groups – but this became obvious only fairly late in the term (although the reading of the novel had been marked as “mandatory” in the course description).

[14] In our analysis we have therefore corrected careless mistakes as shown in Table 2.

[15] It should be noted, however, that, whenever these rules should hinder the annotation process (e.g. when only parts of a token are to be annotated), they can be switched off.

[16] The individual Students listed here were all in CATMA group A, hence Ca-A etc., and have been numbered randomly in the course of anonymisation. Graph 2 refers to CATMA group B (Ca-B) who annotated volume 3 of the novel.

[17] Whenever the diagrams refer to CorefAnnotator in general, the corresponding quantities include the numbers of those groups that were involved in the annotation of the chapters to be compared.

[18] The latter was certainly an issue: although there were full sessions dedicated to annotating the text and there were no oral presentations that students had to prepare other than to present their results, the students found the class demanding and annotation time-consuming (beyond what is usually expected of them in terms of class work).

[19] To clarify the instances, especially for the following individual examples, we have counted and named them in the order of their appearance within those first three chapters of the novel.

[20] While one might argue that there cannot be a difference between “figure” and “role,” in some of the annotations, wrong attributions could be found. One can also regard the split task between identifying a character and their respective role as a speaker or focalizer as a control task regarding the attentiveness of the annotators.

[21] Following the widely used evaluation rankings by [Landis and Koch 1977], the κ value for figure would qualify as “good agreement”, while role would still be considered a “moderate agreement”; unlike modality, which scores lowest possible as a “poor agreement”. [22] Here an epistemic reading, though referring to a future event, works because it refers to a generally known fact (the assumption that second marriages are happier after a disappointing first one).

[23] This has been the case for instance 35 of must. In a dialogue between Mr. Knightley and Mrs. Weston in chapter 5 of the first volume, Mrs. Weston addresses Mr. Knightley, who answers: “Perhaps you think I am come on purpose to quarrel with you, knowing Weston to be out, and that you must still fight your own battle.” [Austen 2012, 27]. One student in the CATMA group attributed the passage to Mrs. Weston as focalizer rather than Mr. Knightley as speaker, despite the quotation marks and the context of a dialogue. The reasoning behind this may be that s/he recognized Mrs. Weston as the originator of must: “you think: ‘I must fight my own battle.’” [24] This has meanwhile been made obligatory in some DH classes – with very good results.

Works Cited

Abrams and Harpham 2015 Abrams, M. H. and Geoffrey Galt Harpham. (2015) A Glossary of Literary Terms. Wadsworth: Cengage.

Austen 1998 Austen, Jane. (1998) Pride and Prejudice. Ed. James Kinsley; intr. Isobel Armstrong. Oxford: OUP.

Austen 2012 Austen, Jane. (2012) Emma. Ed. George Justice. New York: Norton.

Bauer 2015 Bauer, Matthias. (2015) “Ironie und Ambiguität: Annäherungen aus literaturwissenschaftlicher Sicht.” Faktuales und fiktionales Erzählen. Ed. Nicole Falkenhayner, Monika Fludernik and Julia Steiner. Würzburg: Ergon, 2015. 139–58.

Bauer and Brockmann 2017 Bauer, Matthias and Saskia Brockmann. (2017) “The Iconicity of Literary Analysis: The Case of Logical Form.” Dimensions of Iconicity. Ed. Angelika Zirker, Matthias Bauer, Olga Fischer, and Christina Ljungberg. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2017. 331–44.

Bauer et al. 2020 Bauer, Matthias, Sigrid Beck, Susanne Riecker, Saskia Brockmann, Angelika Zirker, Nadine Bade, Carmen Dörge, and Julia Braun. (2020) Linguistics Meets Literature: More on the Grammar of Emily Dickinson. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bray 2007 Bray, Joe. (2007) “The ‘dual voice’ of free indirect discourse: a reading experiment.” Language and Literature 16.1: 37–52.

Cohn 1978 Cohn, Dorrit. (1978) Transparent Minds: Narratives Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Davidson 2008 Davidson, Jenny. (2008) “Austen’s voices.” Swift’s Travels: Eighteenth-Century British Satire and Its Legacy. Ed. Nicholas Hudson and Aaron Santesso. Cambridge: CUP. 233–50.

Ducrot 1984 Ducrot, Oswald. (1984) “Esquisse d’une théorie polyphonique de l’énonciation.” Le dire et le dit. Paris: Editions de Minuit. 171–233.

Genette 1980 Genette, Gérard. [1972] 1980. Narrative Discourse. An Essay in Method. Oxford: Blackwell.

Gius and Jacke 2017 Gius, Evelyn, and Janina Jacke. (2017) “The Hermeneutic Profit of Annotation. On preventing and fostering disagreement in literary text analysis.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 11 (2): 233–54.

Justice 2012 Justice, George. (2012) Introduction. Emma. By Jane Austen. New York: Norton. vii-xxxii.

Landis and Koch 1977 Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch. (1977) “The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data.” Biometrics 33.1: 159–74.

Oberman 2009 Oberman, Rachel Provenzano. (2009) “Narrated Monologue in Jane Austen’s Emma.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 64.1: 1–15.

Pagel et al. 2020 Pagel, Janis, Nils Reiter, Ina Rösiger and Sarah Schulz. (2020) “Annotation als flexibel einsetzbare Methode.” Reflektierte algorithmische Textanalyse: Interdisziplinäre(s) Arbeiten in der CRETA-Werkstatt. Ed. Nils Reiter, Axel Pichler and Jonas Kuhn. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 125–142.

Pollack-Pelzner 2013 Pollack-Pelzner, Daniel. (2013) “Jane Austen, the Prose Shakespeare.” SEL 53.4: 763–92.

Waltereit 2006 Waltereit, Richard. (2006) Abtönung: Zur Pragmatik und historischen Semantik von Modalpartikeln und ihren funktionalen Äquivalenten in romanischen Sprachen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.